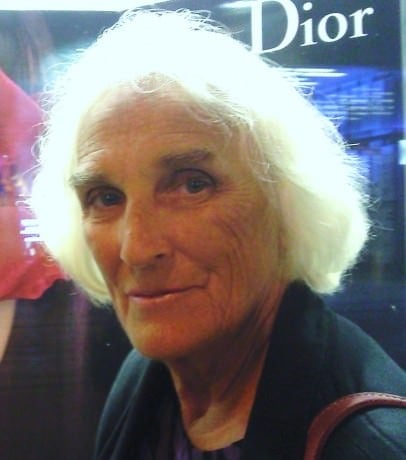

Maida Withers is an artist with extraordinary gifts for dance and choreography. She loves not know and is as interested in the discovery as in the performance. And artist who has reinvented herself multiple times in her career, Withers has always stayed true to her ideals and what drew her to modern dance in the first place. She is an enduring student of life, dance and technological innovations. She has educated and mentored countless dance professionals in Washington, DC, New York City, and beyond, and continues to do so at The George Washington University.

As she gears up for her premiere performance of Collision Course – a.k.a. Pillow Talk, Maida Withers met with me to discuss her career, her artistic process, and her upcoming show.

Rick: Were the arts always a part of your life? Did you begin in the performing arts, or enter them another medium?

Maida: I was born in Kanab, Utah, and from an early age I understood that art and nature are interconnected. I come from a tradition and religious culture where the arts were embraced. Singing, dancing, and storytelling were essentials. Everyone in my family had exposure to the arts, and we could all sing, play the piano, etc. My mother’s side of the family provided nightly entertainment for guests at The Kaibab Lodge, located ten miles from the north rim of the Grand Canyon. In my home, art was part of our natural daily existence.

We have a record in my family’s journal of my love of dance. An entry from when I was seven years-old says, “Maida is dancing up and down the stairs again. Everything’s a dance for Maida.” I think I was dancing a lot. I remember, when I was in the fourth grade, creating performance dirges on our front porch, as cars drove past on the way to the cemetery. We would also do moon dances at night, my three friends and I, out on the street in front of my house.

Kanab was a small community where I could do these ridiculous things, because there weren’t any rules. I could stay up. I could go onto the roof of the cannery where they packaged peas, and sing songs on the wagons at night. It was a safe environment that tolerated my curiosity and excess of imagination.

When did dance become a focal point? What was your training in dance?

Interestingly enough, there was a woman in Utah by the name of Virginia Tanner. She had lived here in Washington, DC and was part of a collective in Dupont Circle. When she married and moved to Utah, she developed the Virginia Tanner School for Dance; and it was all about improvisation (theatre included). I studied with Virginia and began teaching for her when I was seventeen, a freshman in college.

I attended Brigham Young, and received a bachelor’s degree in Dance and Theatre. Then I studied at the University of Utah, where I earned a master’s degree in dance and education. The University of Utah, at the time, had one of the strongest dance programs in the United States. There were a very few universities where they were putting dance in the intellectual setting of the university.

Do you remember a point where your interests moved from dancing other people’s choreography to creating your own?

I don’t recollect a specific moment. The young artists of my generation were naturally irreverent. Within the chaos that emerged and morphed into the Vietnam War, ideas of changing the world of dance were emerging. They were presaged by John Cage, maybe even more than by Merce Cunningham. We particularly asked: “What structure works for me?”

The 1960s were about establishing new parameters for the structure in dance. It wasn’t just a revolution against classical narrative, or a revolution against a certain kind of language, but it was a larger picture. We wanted an answer to the question: “What is the relevance of modern dance in the society?” The traditional modern dance purposes for making dances didn’t serve our purposes anymore. Their purposes weren’t sufficient. We were out on the streets demonstrating against the Vietnam War, wondering how to connect our real lives to our passions.

What was the dance landscape when you formed the Maida Withers Dance Construction Company? How has being in Washington, D.C. influenced your company’s trajectory?

When I moved to Washington, I was invited to replace a friend from Utah who was teaching in George Washington University’s dance program. She took a Fulbright and I took her job. That’s not the end of the story; forty-seven years later.

At that time, GW sought to crystallize the undergraduate dance major, and the graduate program. So, with the incredible Elizabeth Burtner, we first created a curriculum for the master’s degree curriculum. The second year we designed a curriculum to offer a bachelor’s degree. We were sly. We were in the School of Education, and during the summer when the faculty was frolicking, the dean approved the degrees without vote, or discussion. We attracted a really wonderful group of people. When they graduated, I invited six of them to participate in The DC Dance Collective.

We started doing improvisation events out on site locations, and at GW. The company really began as a collective. Of course, I was the motivating factor, having been their teacher/professor. I was the one that wanted it to happen. I was the one that got them to be involved. Interestingly enough, two of the six dancers were visual artists by their academic backgrounds. They left the visual arts to come to dance for a master’s degree.

So in the original company of six, there were two practicing visual artists. The Maida Withers Dance Construction Company (MWDCC) emerged out of that collective group of people. That group of people was together for seven years. Can you imagine it today? It’s unheard of today, it couldn’t happen. It maybe does. The Dance Construction Company came into existence in 1974. It has had many different phases. Phases where the board was more active, phases where the board was absolutely inactive. We have tracked the life of dance in Washington, and nationally. For example, we were doing all of these interdisciplinary works in the 1970’s. In the 1980’s those were huge projects, like “Einstein on the Beach.”

In the 80s, dance in Washington was in its most recognized state. There were some very good sponsors. Dance’s status was equal to theatre and music, at the time. That is not as true today. As theatre grew and developed, dance did not keep up the pace. There are no theatres for dance, except for Dance Place. The huge expansion of theatres in Washington, DC has been for theatre. Dance has not had access to most those spaces.

Now, I will say this. When I was on the Board of the Washington Project for the Arts, we were having intense chats when they stopped doing so much dance. The director at the time said, “You have to get out of town to have any credibility in town.” And I thought, “Ok, good advice.”

So, I did my first international project in 1981. And I thought, “This is nice. I can travel abroad and have someone produce and present me, and have an audience. Or I can stay in Washington and self-produce and lose, in the 1980’s $5,000 or $10,000, or now $25,000.”

I am grateful that somebody turned me and pushed me into the universe at large. It’s always been my goal to perform twice, or more, abroad. Washington is a where international connections abound. It is the best place to pursue international work.

Collaboration is prevalent in many of your choreographic works. How do you approach collaboration with an artist of another medium? In technological collaboration, does the technology interest you first, and then you incorporate it in your work?

Before undertaking my first collaborative work, I went to the DC Commission for the Arts and asked for its support. I received an invitation to appear before the Commission to discuss the prospects for, and shape of, collaboration in the world of dance. So this is how far we’ve come.

“Collaboration” is a much used, and greatly abused words. It can mean so many things.

Because the MWDCC has always included dancers who are visual artists, there has been a certain level of collaboration that is differently defined with them than with outsiders who may be ignorant of dance, and the demands of theatrical settings.

In contrast, when you collaborate with someone like Steve Hilmy, we know each other’s artistic needs

Our best collaboration was when I was in Africa as a cultural envoy. Throughout three weeks we rehearsed every day for eight hours. We were dancing with ten professional dancers in Africa. Steve participated in every rehearsal. He had his computer set up. He was playing for us live. Sometimes he’d turn the sound off and compose, and then he’d return to playing live. That’s the best collaboration, when all of the collaborators are present. Is that viable collaborative art form? On small, little collaborative projects, yes it is. On big, monumental projects, no it is not. People are going to work independently and come together.

Collaborations, today, have changed. Now, I post my choreography on Vimeo, allowing the musician access to that. But, Vimeo is not rehearsal; it’s not the truth. However, in a way, it is more viable. This technology permits collaboration among artists in different cities and time zones.

The way time is pressing all of us today to create art is the primary force changing collaborative relationships from intense intimacy to pragmatic partnerships. All of the arts are struggling to find a balance between time and committed, close relationships. In my instance, this new balance elongates the time spend on a work, because you can’t compress it into three months. We don’t have the money to rehearse five days a week for three months. That has an interesting influence on the work. It’s different than compressed time.

Technology seems to fit the nature of some of my choreography, which is deeply philosophical (about creation, about the human being in the creative process of living and being). My works are so complex and elaborate in movement that people say, “Would you please stop introducing technology in your work so we can watch the intricate choreography?” I’ve made a really complex decision. Fortunately for me we’re in a generation of multi-tasking, so my multi-environments in the theatre are perfectly in sync with the way the young people’s eyes, and minds, and heart can experience the work.

How did you come up with the concept for Collision Course – a.k.a Pillow Talk? How has this process been similar or different from your process in the past?

MWDCC held improvisation events every six weeks; tiny pieces in an evening-length work. Once, I brought in pillows and heavy brown rope and we tied pillows to ourselves. The whole improvisation was with pillows flying on the end of these ropes. Years later, we were going to do an event at a gallery, and I thought, “Maybe we can do that pillow thing.”

Eventually, I found thick packaging tape. So I said, “Oh, we can just tape the pillow onto body parts.” Because these pillows were taped to us, we could collide with each other. I could throw a pillow back over my head, hit you, and you fall down on it. “Collision Course” came because of what could happen with our bodies being padded.

Then, during a telephone conversation my son Eric said, “Well, what is the pillow talk? What are people saying when they’re on the pillows?” And I said, “Pillow talk. We need to have text.”

In dealing with relationships, I didn’t want to make any commentary about male/female love, male/male love, or female/female love. I don’t know enough about those things, but I do understand the complexity arising from relationships. What happens? Fear, remorse, vulgarity, sensuality.

I had choreographed forty minutes, and never repeated a movement. And then I thought, “How can we take this material and transform its nature? How can we turn it into violence? How does a joyful relationship, that movement, morph into remorse, or regret, or frivolity?”

This piece is not a narrative, but it is definitely telling a story. It’s almost surreal, but we think of surreal as negative. It’s not surreal like that. It’s like when you see one of Dali’s melting clocks. That’s not so horrible; it’s just a view. So Collision Course – a.k.a. Pillow Talk is a view of relationships; my view and the dancers’ view.

This work centers around four characters. They’re not people. It is about the elements of relationships. In two of the duets, the woman escapes from the man’s presence, and in the other, the man escapes from the woman’s presence, but they’re not a couple. It’s about the discomfort; being uncomfortable in that relationship but being invested in the relationship and wanting to preserve your own self. When you say relationship, it implies that there’s more than one person, but in that moment you’re still only you. You are yourself. It’s not about what happened in this relationship between this couple. It’s not obvious like that. We have vulgar gestures. There are a lot of them. The subtitle was Voyeuristic Views in the Bedroom, but it’s not like people having sex. It’s those gestures and things that happen relating to love are in the piece.

The great thing about premieres is that you learn a lot in a first presentation. There’s nothing like seeing the first presentation of a work. It still has the essence of what goes on in rehearsal in it, because it’s still in a raw stage for the people who are enacting it. The dancers don’t know quite exactly how this is supposed to be expressed. So the audience has the pleasure of discovering with the performing artists, “What is this work?” Because this is so intimate and personal, I think it will be really important for audiences to see it in its first presentation. These dancers are going to be discovering how to present this intimate, sexual aura. The abstract nature of the work demands that the dancers commit to the way that they can express this innuendo and the implications of this material.

I call this work dance theatre because it’s not like theatre in a substantive way, but yet it is. These are personal moves. These four dancers have taken this in. It’s a piece that will take on a certain life in performance.

It feels a little odd choreographing a piece that’s as common as exploring love. It is love for the digital age, rather than love for the renaissance. It’s definitely love for this time. It’s a sort of stupid idea, but I don’t know how else to express it.

Where do you see The Maida Withers Dance Construction Company going? Where do you see the DC dance scene going?

Dance is re-emerging now. Some young companies are exploring new ideas and finding new audiences. The reason I think it’s happening is that we have a limited support system for educating the public about dance, how it works, and its emerging. Traditional communication channels are insufficient. New media is making change possible.

Getting an audience and garnering support is in a new day. Most companies are functioning as independent artists, and not a company, per se. They have the appearance of companies, but in actual fact they are driven by one person’s vision. That person does everything. They write the press releases. They’re engaged at every level.

When you don’t have a mechanism for dialogue between the dancers and companies, where is the community for dance? If you have limited dance venues, dancers will either stop dancing or become managers or teachers. It’s going to disintegrate.

The economy and our cultural values are challenging making artwork all together. Do you have the time for rehearsal? Can the people afford to commit to rehearsing? It used to be easy, we could rehearse three and four times a week. People cannot rehearse three and four times a week for a dance event. They can rehearse twice, maybe, but for how many months? And so these projects string on. They get to be a year long to do one event. You rehearse for eight months to do two performances in Washington, DC that are self-produced?

Dance today too often relies on somebody else’s agenda. I have my fortieth anniversary in 2014. How am I going to celebrate a forty years in Washington, DC ? I’m probably going to ride on the coattails of others.

https://youtu.be/RLQvTpxm8HQ