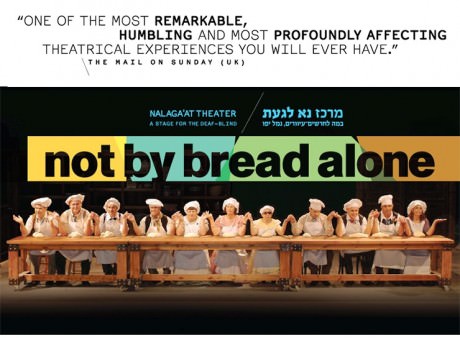

Not By Bread Alone: Extraordinary Food

Before taking my seat for Sunday’s performance of Not By Bread Alone, I stepped into the men’s room and blew my nose — really honked it. The guy at the next sink looked concerned. “I’ve heard that they bake bread,” I explained, “and I want to be able to smell it. This’ll probably be the only time I get to smell the progress of a play.”

I went in hungry because I’d heard that when the bread is ready everybody goes on stage to eat with them, and I wanted their bread to go into an empty stomach.

‘They” are the Nalaga’at Theater Ensemble, eleven Israeli actors who are deaf and blind, so smell is the only sensory platform I have in common with them. Except for touch — ‘Nalaga’at’ means ‘do touch’ in Hebrew – but that comes at the end.

To smell this play, I left home at 6:30 a.m., drove to Washington, DC, caught a bus in Dupont Circle, rode it all the way up the New Jersey Turnpike, disembarked at Penn Station, and then walked 36 blocks downtown to Washington Square. “Why?” I asked myself near Philadelphia.

Because they’re deaf and blind.

A better reason would occur to me later.

Because they’re blind and deaf, these actors face a double challenge: they have to perform without being able to see or hear, and they have to make me care about their work for some other reason than the fact that they can’t see or hear. How are they going to do that?

After a recent performance, one of the actors told the director, Adina Tal, who can see and hear, that he was tired of shallow audiences. “What do you mean?” she asked.

“Everybody says the same thing,” he complained. “‘You’re amazing, they say. You’re all so amazing! I want to know what they think of the show.”

I want to know what he thinks, period.

I contemplate that question as I enter the Skirball Center. The house lights are high and the stage lights are low. We hundreds of patrons mill about, find our seats, call to one another, wave, and kiss, while ten middle aged men and women stand on stage at wooden baker’s tables kneading bread dough. They wear aprons and the kind of floppy baker’s hats that make you think they might do something funny. Most of them seem to have their eyes closed. Do they know we’re here? Organ-grinder-sounding music plays, and the woman on the end sways in rhythm with the music. Can she hear it? Is she nervous? What is she thinking? How is she thinking?

Thinking for a man like me means having language in your head, but most of these people have never heard language, so what must thinking be for them?

Yes, I decide, they know we’ve arrived and we’re settling in. They know they’ll have our full attention by the time they finish kneading. “Baking bread provides a common time frame for the actors and the audience,” Tal explains. A structured process, with a beginning, middle, and end that you don’t have to see or hear.

Tal, the Founder, President, and Artistic Director of the Nalaga’at Center in Tel Aviv, doesn’t work with blind-deaf actors to be nice. “I’m not a social worker,” she says. “I’m not even sure I’m a good person. I do theater. I wouldn’t do this kind of theater if it weren’t exciting.”

This kind of theater is like performance art in some ways. The actors play themselves, not characters, and the play gets its power in part from our knowledge that their plight is real. People would be outraged if you tried to do this show with actors who are neither blind nor deaf. It would be reductive, presumptuous, patronizing, wouldn’t it?

Itzik Hanuna, who was born blind but could hear until he was eleven — and who thus can speak — explains that the play is a series of vignettes in which different members of the company enact the things they dream of doing. We all have dreams, he says. And the play’s most compelling scene is a collective dreamscape, each of the actors doing something he dreams of: Genia waltzes with Igor, Yuri walks on stilts, Bat Sheva glides and floats on a wooden swing, Yurani shaves with a straight razor, everybody acting out his dream, all at once, in the half-light of sleep or of memory.

In another scene, Shoshana says she dreams of having famous Yuri do her hair, so we watch that happen, step by step. Rafi dreams of being a sculptor, so we watch him position Tzipora’s body, check her pose with his hands, and then chisel an imaginary block of stone. We watch Yuri meet Bat Sheva, woo Bat Sheva, win Bat Sheva, and then break the goblet the two of them just used to seal their marriage covenant.

But there’s no story in ‘I dream of doing this’ unless I can’t do it for some reason. Does it make a difference to the story-telling if the reason’s real?

“After we’d been working together for three months,” Tal said, “one of the actors told me he thought what we were doing was stupid. ‘What would you rather do?’ I asked him. ‘I want to do Gorky,’ he said. ‘Maxim Gorky.’ ‘You’re deaf and blind,’ I said. ‘How are you going to do Gorky?’ ‘You’re the director,’ he muttered. ‘That’s for you to figure out.’”

Many experimental theater pieces impose artificial limitations on their actors in order to discover what those limitations may force the actors to invent. I want to see Synetic Theater do The Tempest, for example, because I expect the limitation they impose on their actors – don’t speak, even though you can – to show me something about Shakespeare, about theater, about the consequence of limitation, about people, about the mystery of people. I want to see that mystery in every play. And it has to go beyond the mystery of what it’s like to be both deaf and blind, because I’m not deaf, and I’m not blind, but I traveled all day long to get here, so I want to know the secret, if there’s one to know. If it isn’t knowable, at least I want to stand beside it for a while. Maybe there’s something to glean from its shape.

I stood beside its shape at the end of this play. In the final act, the cast expands from eleven to a hundred. The bread comes out of the oven, and the actors stand behind their work, and a translator blesses the challah in the traditional way: “Blessed are you, Lord, our God, who brings forth bread from the earth.” Then we other actors come down from our seats to the stage where those eleven men and women had stood beyond our reach an hour and a half before, where they had taken the first step in the narrative structure shaped by baking bread, the step that has to be taken alone — only one person can knead a ball of dough.

“While the bread is in the oven, thoughts appear,” one of the actors said earlier.

The bread is steaming on the tables now, waiting for the last step in the narrative structure, which has to be taken together. We break loaves, dip them into oil, and eat. And we tell the actors through interpreters that they’re amazing, that we love the show, that their bread is delicious, and we shake their hands.

“It’s important that whoever I meet shake my hand,” said one of the actors, “because that’s how I know they exist.”

So we shake their hands because we exist and we want them to know it, and we eat their bread because we’re hungry, and it fills the shape of the secret inside us.

A stooped old man in black put his wife in a safe place at the front edge of the stage and then waded toward the tables. He disappeared into the crowd. A moment later he emerged with bread. Most people were tearing off little pieces so there would be enough for everyone, but this man had two whole challah rolls, big ones, bigger than his hands. He bent over them and held them near his body as he shuffled toward his wife, followed by some hunger he had known.

“Here’s bread, Miriam!” he called. “Here!”

He was well groomed, and his wife was wearing jewels. She reached for him and they came together.

I could have stood and watched them eat forever.

Running Time: Ninety minutes, with no intermission.

Not By Bread Alone plays through February 3rd at New York University’s Skirball Center for the Performing Arts. NYU Skirball Center is conveniently located at the corner of LaGuardia Place and Washington Square South at the base of NYU’s Kimmel Center for University Life. The main entrance is at 566 LaGuardia Place, in New York City. For tickets, call the box office at (212) 352-3101 or purchase them online.