After seeing Iron Crow Theatre’s grotesquely fascinating piece Apartment 213 about Jeffrey Dahmer and going back to familiarize myself with the Dahmer case, I was not satiated in my thirst for knowledge about why someone would want to create such a vivid and exploratory piece of theatre about one of society’s better known ‘monsters’ – so I was determined to seek out the answers from the theatrical mastermind himself. In a sit down interview with Playwright and Performer Joseph Ritsch, I ask the questions that everyone might ask after viewing this incredibly compelling performance piece. The answers are stunning; a level of humanitarian brilliance shining into the work as Ritsch gives us insight to his creative process.

Joseph Ritsch.

Can you tell us a little bit about the show’s background. I understand this is not the first performance of the production.

Joseph: This is actually it’s third incarnation, I’ve done it twice before. I actually wrote the piece as a project for part of my MFA coursework at Towson University. It actually came out of a class assignment. And it has sort of gone from this 5-minute performance piece for class to now. I was actually working on a different piece at the time a Jean Genet piece and my teachers said to me that they liked the Jean Genet thing but they really felt that I had something different going with this particular piece.

And I actually took this piece, all five minutes of it and applied for Wordbridge— which is a National Playwright’s Lab program that gives new works a chance to be selected and worked on. And it’s a summer program that essentially results in a two week residency where you are given a full team: actors, directors, tech designers, everything; to really explore and develop your piece. There are a handful selected every year and in the summer of 2013 Apartment 213 was chosen because that year they were looking into projects that had more of a movement approach to them.

And you know then it was still a five minute “treatment.” And they assigned Will Manning, who is still currently acting in the show with me, to my team as the actor and I had known that I had only ever wanted the one actor for the victim role and he’s been with the project ever since.

Iron Crow co-produced the project, unfortunately Iron Crow was so small then, they were still getting started and hadn’t yet established the wonderful following and support that they are still developing now; so despite great press (which included making the top 10 with City Paper) the show didn’t get very much exposure in its initial two week run.

Then we took it to New York City, that was a year later in the summer of 2011 as a part of a 4 show festival that Lee Breuer was hosting in conjunction with MabouMines. It was four different productions we each got four nights but it was sort of in this really tiny space in the middle of New York City in the middle of the summer, so again, while I was grateful to have another opportunity to further develop the project, the audiences and exposure were limited.

This production in 2013 with Iron Crow Theatre is the third incarnation, a lot of people were asking for it and have continued to ask for it, and with the current theme of their season it only seemed appropriate.

The big question on everyone’s mind is why write and conceive a play about Jeffrey Dahmer. Why choose him?

I was trying to remember earlier today— knowing that we were going to have this conversation— why I chose it for the project in class…it was a great class with a guest faculty – David Kennedy – who is a very successful director who came in. Each week he gave us these exercises, he called them ‘etudes’ and there was specific things that had to show up in each etude. And for this one we had to have a song in a language other than English. And I somehow stumbled across the French version of Nat King Cole singing “L.O.V.E.” And how I leaped from Jeffrey Dahmer to that? I’m totally blanking. I think I probably saw one of those biography documentaries or something, which I’d probably seen four billion times, but I saw it again…and it just, I don’t know there it was.

So when I was nudged to sort of develop it and do actual research I was drawn to kind of three main things. One, and the fact remains, was he telling the truth or not is something that we have to think about, but that being said, he claims that he had remorse for what he did, which is very rare for a serial killer in particular.

But what was even a greater impact on me was that he claimed that he knew what he was doing was wrong in the moment but was physically compulsed. And I just couldn’t even begin to imagine the level of sadness and despair that brain held knowing that what he was doing in the moment was wrong but not being able to stop it. Combined with his claims that he desperately wanted a relationship but felt he couldn’t connect intimately with someone who was conscious.

And then the political side of it was I think that it is very easy for us as a society to point fingers and call someone a “monster” and then in regard to that, where is our responsibility? With this particular case there were so many opportunities for him to get caught, this went on for years and years and years.

You know the moment that happens in the piece where the victim sort of wakes up and turns into Jeffrey’s dad and says, “What’s in the box?” that was very very early on. And I have said over and over again, “Listen, what he did was a horrible, horrible, horrific thing…he killed 17 young men but I just don’t think it can be that black and white.” Mental illness is not that black and white. Humanity is not that black and white.

I don’t mean any disrespect for the deceased, their families, and the horrible tragedy that they went through but there’s a reason that happened and where is our responsibility in that? And it was a racial thing, and obviously in the gay community…you know being gay was very different then, particularly in the Midwest. He was caught drugging men, there was a particular bar that he’d hang out at in Milwaukee that had these “back rooms” where you could meet a young gentleman and rendezvous in these back rooms, and he was caught drugging young men there so he was kicked out and banned from the bar. But the gay community did nothing about it. You have to remember the times, you know calling the cops and saying you have someone that’s drugging people in your bar— well then your bar would get shut down, but still, where is the responsibility?

Then there is another moment in the piece, where the boy who was actually 14, you know when Will stumbles downstage, that moment…well Dahmer told the cops he was 19 and he was actually 14. This boy was completely naked in the street, incomprehensible. He was severely sedated and woke up in this drugged stupor but he couldn’t vocalize what was happening because he was so drugged. And two African American women saw him and called the cops. And the cops believed Jeffrey over these two women. These two women had said “we know this kid from the neighborhood” but the cops believed Jeffrey. They were fired, the cops, eventually, but I mean you had to think about the demographic of the time. Two white male cops, two black female people calling it in and then a white male telling his side of the story…so again, this points back to the question I keep asking “where is the responsibility?”How are we letting this happen so that was another thing that I was interested in exploring.

You didn’t want to just write about Jeffrey Dahmer, you also wanted to play the Jeffrey character. Was it always set up that way or have you evolved into playing him?

Like I said it came out of a class project. I didn’t seriously think it was going to be anything beyond this one class project because you know the way this class was structured it was a new project every week. So I thought here I’m doing my five minute etude and it’s done. I did have a victim in the five minute piece but he never spoke, he was literally just a body that appeared at the end. So it just kind happened. And you know the MFA program at Towson is about the total self-produced artist who writes, who directs, who acts, so it just kind of fit the structure of what I was getting my MFA in.

The reason I call him Jeff…do you want to know? If you watch the interviews with his dad, his dad calls him Jeff and I just thought that was interesting. Because you know in the media it was always “Jeffrey Dahmer. Jeffrey Dahmer. Jeffrey Dahmer.” So I just thought that it was interesting surprise for me and that’s something to just think about how our public personas, whether we are a serial killer or not, are very different from the people we have intimate relationships with in our lives, the people like parents and stuff like that. And having your parent call you by your nickname…there was just something about that that I was sort of drawn to.

Going back to the original question…I think what I have discovered with this round of the production, because I’m so much more relaxed as a creator and a writer of the piece, I feel it’s in a solid place for me for that part of my creative brain. And also having Stephen Nunns come on a bit later, I was directing the piece at first as well and I realized that I just got to a point where I needed an outside eye and someone to help. And he is just amazing. So now that I’m not worried about that because I have someone I really trust in the director’s chair, I feel that the writing and creative part is in a really good place, I’m finding that it makes it much harder to do the acting part of it because I don’t have these other things kind of distracting me. And it’s a really sad place to go, inside his mind.

I’m not one of these actors that has a hard time going in and out of difficult things. But it’s just one of those things that I’m finding harder now, which I guess would happen as the piece gets deeper and evolved. So that’s the hardest part about it because it’s a really sad place to go, but I’ve chosen to do this, so it’s fine.

What was the dramaturgically creative process like for you in cultivating this piece?

Well I watched all the interviews with him which were of course obviously post-incarceration but pre-murder. He was murdered in prison by another inmate. So those were really fascinating. And they’re all on YouTube so if you get a chance to look those up. Do you remember Stone Phillips, his is the famous interview with Jeff and his dad and then there’s a separate interview with his mom. His parents were estranged…divorced and in my opinion I think that might have contributed. She’s deceased now, but there seemed to be a lot of venom between them. It didn’t seem like it was a very good relationship between them, not a good split, and there is alleged mental illness on her side of the family which she had denied…but I did all that. A lot of the books that are out about him felt super sensationalized so I didn’t do a lot with those. I did watch the film Dahmer that Jeremy Renner was in, and I do think it’s an interesting film. I watched the trial which is where I decided to do the testimony sequence from. That scene where the victim that got away is on the stand.

So to connect the research to the creative process what was fascinating about watching him on the stand, the one who escaped, I found him to be deeply detached and this is going to sound like a major contradiction, but connected at the same time. And this idea of having to tell that horrible story of getting away and almost not getting away, also now with the knowledge of the 17 men before him, how could your head just not explode? And just watching him recount the details of it, in one way seemingly very detached but you could see in his eyes how difficult it was. Which is where I got the idea of hearing only his side of the questioning so it was like just his side of the story. So that’s why it’s just snippets of his answers there.

You use a lot of strong and very image specific videography in this piece. What was your intention and focus behind these choices?

I think overall aesthetically I wanted the piece to feel like a nightmare, to feel like Jeff’s nightmare. So if you wanted to look at it chronologically I saw this as after he was arrested, maybe possibly when he was in prison, and looking back into the world in kind of a nightmare state. So the video was a way for me to explore these elements that were in his head; snippets of things that would come on and black out, come on and black out. It was also a way to dramaturgically include some of the factual stuff without having to do that with exposition. You know hence the chocolate factory, which if you don’t know the history when you first see it a lot of people are probably thinking “why am I watching a chocolate factory?” But it was a big part of him. There’s chocolate. There’s meat. There’s porn.

Sex and sexuality was very much a part of what was going on. One of the reasons I was drawn to the images of the naked go-go strippers was that sense of voyeurism that you get with that and this idea of someone from the outside looking in and trying to represent a detachment from the intimacy of it all while being highly sexualized at the same time. Juxtapose that against a very familiar standard love song, like all the Nat King Cole music. Which I found out later on was music from his parents era, probably stuff they had listened to, so I like that connection. And Nat King Cole is the quintessential love song crooner, so then there’s that.

How did you go about making the music choices for this show that create the stark contrast of graphic and grotesque imagery that plays out in these scenes against these sweet love songs?

That ties back to the idea that it’s not so black and white, right? It’s not. And I think it would be expected to choose some hardcore violent metal rock or something. But I wanted that juxtaposition and I wanted to find moments that for him…he wanted the romance. But you know, he had it with mannequins— dramaturgical side note he broke into a department store and stole a mannequin. A male mannequin when he was younger, which he was later found out about and made to return, but that was really early on. He stayed at the department store until it closed and then stole the mannequin. So that ties in, the romantic music because it showed those moments of just desperately wanting to have that romance but being unable to.

And then I know I mentioned having used the “L.O.V.E.” in French during class so I kept that and switched to the English version. And then I started looking at how Nat King Cole has a love song CD of all the love standards recorded for that time. And then when I found “Stay” that was just the perfect fit for the victim, literally with him not staying there when he was supposed to. And the idea of Jeff literally trying to keep these men and of course we know that didn’t work out.

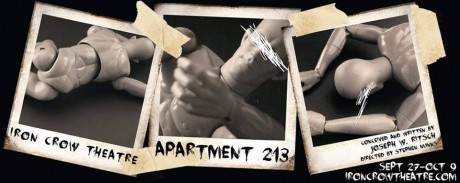

From the beginning I didn’t want the piece to feel sensationalized or in any way gory, grotesque is fine, but I was trying to find ways to represent the violence particularly of the bodies? So I found, he’d actually a little artist’s model doll is what he is, and I did all the photography for the models and I just thought, ‘ok wow that’s really interesting’ and then once the mannequin got introduced to the piece it seemed like the perfect progression to have him show up. And the tie in with the angel imagery, that sort of grew too as the piece progressed.

How did you make the decisions for which victims to incorporate into the piece? Dahmer had 17 and you honed in on a very specific 3 and then the boy who got away, so what was the thought process there. Why them?

The victim character evolved as well. My intention at first was that although the victim would be an actual actor, as opposed to some special effect dummy or something, would never speak. But then when I got to Wordbridge and we started improving things him speaking started to make more sense to me. I wanted to keep it having a sense of ‘everyman’ as the victim but at the same time how do I remain true to the scope of the numbers? I guess I technically talk about four of them and then the man that got away. I had been debating, going back and forth about expanding to three actors playing the victims to get more of a sense of the numbers but that just didn’t feel right. Aesthetically it’s more interesting to have just the one man playing the victim. And it ties into the nightmare because the whole thing is obviously not realism, so the idea that this one being keeps morphing into different victims. It also for me both as a writer and as an actor this idea of him knowing what he was doing was wrong but not being able to control it— that idea of “oh my god, it’s happening again. Oh my God, it’s happening again.” I think it’s really interesting to have just one actor who suddenly is the “oh my god, it’s happening again” guy.

And this is one of those pieces where Will is just such a big part of it for me both as a writer and as an actor that it would be really really difficult to introduce anyone else at this point. Will is so invested in this piece, he’s been with me since the beginning.

What is your approach to balancing out the dream verses the reality in this production?

When we were initially developing what I refer to as the “victim scenes” which are more of the traditional dialogue scenes, Will was invested in some specifics of the differences of some of the victims. I was just really drawn to the 14 year old. I was just drawn to his first victim, which is the monologue about ‘side of the road,’ and then there was the man that got away.

So then the 14 year-old, we call that victim “the virgin” once that got more solidified, we knew that we wanted a second victim to balance that out that was very very different. And again this is very much imagination because obviously these people are not involved in the creation of the piece, but a number of these guys were on the fringe of society, so to speak. And they needed a little extra money and Jeff’s thing was offering money for pictures— finger quotes, right? So we decided to go with a victim that was more from that kind of world, more aggressive, cocky, very much not a victim in order to create that balance. So the idea that “what if there was a situation where the victim wasn’t that easy for Jeff? He wasn’t drinking the drink and he was confident and he was aggressive…” also playing around with the idea that that sort of sexual aggression would make Jeff extremely uncomfortable because he couldn’t handle that, hence the trying to turn them into zombies. But that was the idea of where the two main victims came from. And of course the testimony for the one who got away.

I played around with the idea for more but I feel like it just feels like the right length right now and anything else would just ruin that. I hate going into a show and feeling like there was an obligation to make it a certain length. You know tell the story, leave them wanting more and that’s how it should be.

You have incorporated a bit of mythology and imagery based on that mythology into this show. Can you talk a little bit more about why you chose that approach?

They call it the happy accident. You know the chocolate factory where he worked, it doesn’t exist anymore, but it was actually called Ambrosia Chocolates. Ambrosia is the food of the gods. And when I started looking at some of the mythology stuff, just how wonderfully it all sort of fit into place. You know there is no dramaturgical fact that says Jeff cared or was interested in or even knew these stories, but that’s where the theatrical creativity comes in. But I just thought “wow, this is just too good not to make this connection.” And then the Ganymede story, and the power and sexuality in that— that’s where that came from.

And then this idea that if he couldn’t keep them alive at least he’s making them into angels. And there is a quote that happens in the ‘boy from the side of the rode’ monologue where he talks about “…what if he died now before anything bad got into his head?” So this idea of innocence that evolved, and then the feather imagery of the wings, it all just came together.

You use a lot of physical and verbal repetition in this production, and what is it about that repetition that speaks to you as a performer/creator and makes it so important to use in this performance?

Again, tying into something earlier we talked about, the nature of it was that it was so repetitive, it did happen 17 times…but what for me there is that it seemed very ritualistic. The going out, offering the money for the pictures, come back to my apartment, drugging the drinks…it was never random, I mean not in the sense that “oh I’m going to go out tonight and kill somebody” but there was a ritual to the pattern. So that’s the repetition being very important to me for that, particularly with the pickups. And then going back to the “oh my god it’s happening again.” Like here I go again, same story different day and I can’t stop it. And then that just kind of ended up happening with a lot of the movement as well, to be able to represent that concept physically.

We do know dramaturgically that he offered this idea of taking pictures for money, but the actual lines and texts that’s all the fantasy of the writer, my creation. I took the fact of it and developed phrases that I felt fit— and the buying drinks, we knew that happened too. You know before he got caught and then had to do it at home he was buying them drinks and just slipping them crushed up sleeping pills, but the text was mostly my own creation inspired by those facts.

What is the overall message you are trying to send with this piece of performance?

Oh I hate that question! It’s always such a difficult question. I guess it goes again back to the first question, it’s about just not being that easy to simply point fingers and call someone a “monster” when we haven’t walked in their shoes. And that we as a society need to take responsibility for each other and not look the other way. And it’s not about taking sides, for me. It’s not about saying— because what he did was a horrible horrible thing— but there’s more to it than just that.

What has this performance taught you about yourself as a creative artist?

It makes me think about a lot of the acting teachers that I’ve had…they’ve said “you can’t judge the character you’re playing.” No matter how despicable their behavior is you’ve got to connect with them somehow. And for me the connection here is that deep deep sadness and the longing to want to connect to someone. And I think that’s what makes the piece universal, which is why many other people respond to it the way they do. They go “oh my god I can’t believe I’m seeing humanity in this man.” But I mean at the end of the day he’s a human being, a very troubled human being that did horrible horrible things but a human being nonetheless. So for me as an actor going into it I can’t get myself caught up with the violence of it and that side of it, I have to go for the sadness and the longing. I do think one of the most rewarding things is that now the modern audience is sort of trained to want to see this linear…A to Z realistic play that they can walk out of not feeling stupid…so I think it’s somewhat risky to put something out there that’s nonlinear and has all these elements that are very discombobulating and still have people respond to it the way they have, having them be drawn in and still be moved.

Apartment 213 plays through October 12, 2013 at The Baltimore Theatre Project— 45 West Preston Street, in Baltimore, MD. For tickets, call the box office at (443) 637-2769, or purchase them online.

https://youtu.be/QywKy2VF1pA

https://youtu.be/vPMBfX7D4WU