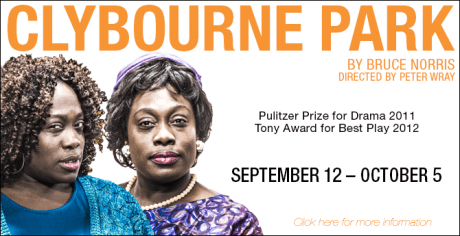

A Then and Now Tour: Clybourne Park at Maryland Ensemble Theatre

Taking a modern twist on Lorraine Hansberry’s seminal play, A Raisin in the Sun, Bruce Norris in his 2011 Pulitzer Prize-winning comedy, Clybourne Park, satirically juxtaposes the evolution of American race and class relations in the late 1950’s to the 21st Century, resonating the clichéd expression: the more things change, the more they stay the same.

In the cozy, intimate, 100-seat Maryland Ensemble Theatre (MET), Director Peter Wray exhibits an authentic interpretation of Clybourne Park, pivoting between two time periods set before and after Hansberry’s play, dramatizing historical parallels, as the tides of history and politics shift.

Designer, Eric Berninghausen, transforms the stage, from one act to the next, beginning with a formal, yet tastefully decorated home, drawing the audience’s attention to its mint-colored walls and traditional accents reminiscent of the late 1950’s and, later, transitioning it to a heavily worn, graffiti-splattered, trashed ramshackle eyesore 50 years later.

The first act opens in 1959, on set the living room of grieving parents, Russ (DC Cathro) and Bev (Julie Herber), who are packing up and preparing to move, after the sale of their home in the white, middle-class Chicago neighborhood of Clybourne Park. As the scene unfolds, they receive a visit from their local congenial clergyman, Jim (Jack Evans), as well as a territorial neighbor, Karl (Brian Irons) and his deaf, pregnant wife, Betsy (Shea-Mikal Green); Karl abrasively informs them that the family buying the house is black, and essentially pleads with the couple to back out of the deal, for fear that area property values will rampantly decline if “colored” residents move in.

Irons is convincing as Karl, the overt bigot, barreling through without social tact or self-consciousness, while bringing considerable humor, acerbic as it may, to the forefront. Green, as Karl’s wife, Betsy, is poised in her portrayal of a deaf, pregnant Scandinavian, striking a delicate balance of vulnerability and will. Ironically, Betsy is the least deaf of all of the characters, as she makes an earnest effort to clearly understand what the others are saying. Her pronounced pregnancy is a visual reminder of change and renewal, as well as the undercurrent of tragedy plaguing the house.

Evans, as Jim, is credible as the likeable and familiar-looking priest, openly transparent with his facial expressions and body language, walking a tight rope to exercise great restraint and continued civility amidst Russ’ disparaging vulgarity and violent tendencies.

Inevitably, the gloves come off, insults are hurled and heated arguments ensue about the potential problems of integrating the Clybourne Park neighborhood, and both couples awkwardly call on Russ and Bev’s black housekeeper, Francine, (Rona Mensah) and her husband, Albert, (Brandon Scott Boyd) to weigh in on their opposing views. Mensah smartly depicts Francine as the ever gracious and acutely cautious employee – constantly self-aware, careful in everything she says and does. She plays it safe with her responses: “Clybourne Park is nice.” Albert, on the other hand, is not as even-keeled; he is more emboldened, assertive and direct: “We don’t want your things; we have our own things!”

Cathro, as Russ, is emotionally raw and corrosive. His pervasive stares are haunting; a walking time bomb, he eventually explodes and finally snaps, kicking everyone out of the house, saying he does not care about his neighbors’ economic dilemma after their callous and cruel treatment toward his son, Kenneth (Jack Evans) when he returned home from dutifully serving his country in the Korean War.

Herber, as Bev, is a bit uptight in both her appearance and demeanor, donning a perfectly coiffed hair-do and classic 1959 housewife apparel, and stoic mannerisms, living in a state of denial. Bev fixates on trivialities like word origins and cities ending in the letter “s” to occupy her thoughts, rather than directly combatting her underlying struggles. Both Russ and Bev are mourning in their own way: Bev feeling frazzled and in need of constant movement, and Russ lounging in his pajamas, eating a tub full of ice cream and reading the National Geographic.

Fast forward to 2009, Act Two takes place 50 years later in the same space, but now it has weathered into a radically deteriorated, dilapidated home (seamlessly transformed during intermission) occupied with a new generation (the same Act One actors reappear playing different characters) – and, the tables have turned. In the intervening fifty years, Clybourne Park has become an all-black neighborhood, which is now gentrifying.

A white couple (Brian Irons and Shea-Mikal Green), seeking to level and rebuild the house, are being forced to negotiate with local housing regulations vis-à-vis a black couple (Brandon Scott Boyd and Rona Mensah), representing the neighborhood organization. The initial discussion of housing codes invariably degenerates into one of racial issues, revealing deep-seated resentment, prejudice and hostility from each of the parties. Once again, the neighborhood association, this time represented by a successful black couple, along with two attorneys (Julie Herber and Jack Evans), pose a road block.

DC Cathro, in stark contrast to his earlier portrayal of grief-stricken Russ, now plays an unassuming construction worker whose ‘discovery’ links up the two Acts and brings Clybourne Park full circle.

Norris’ clever dialogue and dynamic interactions, while drumming up unexpected laughs during what would otherwise be uncomfortable exchanges, deliberately keeps things inconclusive. He highlights and effectively underscores pointed questions about discrimination, gentrification, political correctness, societal attitudes toward anyone “different,” and artfully demonstrates the inability of even the most intelligent, well-traveled, best-intentioned people to productively discuss these sensitive topics without misspeaking, misunderstanding and arguing.

Round and round, the characters in Clybourne Park are cyclical creatures of inarticulateness and inappropriateness. A talented cast of seven actors under Wray’s taut direction keep the sparks flying. They cannot help but repeat themselves, interrupt each other (and often interrupt themselves), erupt in defensiveness and frustration, tell shockingly offensive, bad racial jokes – one even comparing white women to tampons (Lena: “How is a white woman like a tampon?”). While inspired by Raisin in the Sun, Norris’ play, on its own merits, offers a fresh, contemporary perspective to the status of American race and class relations in a compelling, unsettling, yet entertaining manner. Norris does not have the answers, but he knows how to pose questions with bravado and style.

Perfectly pitched and emotionally all encompassing, Maryland Ensemble Theatre’s Clybourne Park is witty, honest, and insightful – truly a needling and provocative theatrical production. Cleverly written, tautly constructed and mesmerizingly performed by the MET cast, it is absolutely worth seeing, analyzing, and discussing.

Running Time: 2 hours and 15 minutes, with one 15-minute intermission.

Clybourne Park plays through October 5, 2014 at Maryland Ensemble Theatre – 31 West Patrick Street, in Frederick, MD. For tickets, call the box office at (301) 694-4744, or purchase them online.

I absolutely agree, this production was SO good. I mean talk about good acting… I was completely encompassed by the performances the whole time and loved every minute of it. I’d definitely see it again if I had the time, it was just great.