You have a right to be skeptical when a symphony orchestra claims to have a unique sound. Down through the centuries most composers of symphonic music have given specific directions about what instruments are or are not to be included in each work. National and world-class orchestras almost never vary from these instructions and can be trusted to put capable musicians at every position that’s called for in the score.

And then there’s the Gewandhaus Orchestra of Leipzig. Bringing two major works to The Kennedy Center last night – both of which had their premieres with this very same orchestra in the 19th century – the Gewandhaus flooded the Concert Hall with its notably woodsy, autumnal quality. This signature of the Gewandhaus persevered throughout a program that surrounded the core sound with everything from a gigantic brass choir to a virtuoso solo violin.

The Symphony #7 by Anton Bruckner, which headlined the program, is a monumental work that can dash the expectations of a listener who associates a classical symphony with a first and last fast movement and reasonably predictable adagios and waltzes in the middle. Rolling out over the course of an hour and five minutes, Bruckner’s Seventh presents a broad opening theme with initially unexpected twists and turns in the melody that eventually interact with other motifs to become reassuringly familiar.

An even broader and more haunting theme in the second movement is followed by a dramatically fast third-movement theme played in the strings against all manner of countering lines from a huge variety of trumpets, trombones, horns and even multiple tubas and euphoniums. Bruckner’s fourth and final movement threatens to crash down the walls with what can sound like the equivalent of ten brass bands. A conductor’s challenge is to make the entire symphony’s progression logical and meaningful to the listener rather than so many gratuitous walls of sound that don’t register as anything more than a random sequence.

In the hands of Conductor Riccardo Chailly, the center of gravity for Bruckner’s music was the Gewandhaus Orchestra’s spectacularly brilliant cello section, which sounds like a dozen identical Yo-Yo Mas. With the cellos placed strategically inside the “bowl” of the string section but slightly to the conductor’s left – a position that in American orchestras is generally occupied by the “second violins” – Maestro Chailly repeatedly thrust his right-handed baton directly at the cellos and then opened up his arms back across the center and right to encompass all the woodwind and brass instruments, as if to infuse the timbre of the cellos into everyone else’s notes.

By contrast, and in an obvious division of labor, Chailly appeared to spend only the briefest of moments cueing the violins spread out across the lip of the Concert Hall stage. Rather, Concertmaster (or lead violinist) Sebastian Breuninger would take Chailly’s beats and repetitively rotate his body around to his section to lead his own forces throughout the symphony. An increasing modern tendency for concertmasters to gesticulate in contrast to the relatively anonymous work of all of their underling violinists often comes across as a mannerism. But in Breuninger’s case it was not primarily in service of his own playing – it was to pull the seams of the Bruckner symphony together.

In the early parts of the symphony, some of woodwinds and French horns did appear to just slightly disagree with one another on the interpretation of Chailly’s larger gestures, making for some choppy entrances. Such an effect can actually occur as a touring orchestra acclimates itself to a one-time shot in a given concert venue, as opposed to its familiar house in its home city. (“Gewandhaus” – make the “w” a “v” and the “d” a “t” and you basically have the pronunciation – is an 18th-century term that translates as “The Cloth Hall” for the orchestra’s original home in a textile merchants’ market. The second Gewandhaus, built specifically as a concert hall, was essentially destroyed in an Allied bombing raid in 1944, while the current Gewandhaus, constructed in 1981, can be seen on its Facebook page.) As you would expect, any entrance issues disappeared during the second half of the symphony’s progression.

Along with the cellos, special distinction in the Bruckner goes to the double basses, the entire section of which visibly played as if their huge instruments were actually nimble playthings worthy of a bravura performance. And the principal trumpet, for his deft work in numerous high-flying and perfectly played counter-lines in the third movement, has a job waiting for him in any Broadway pit if this gig with one of the world’s most venerable symphony orchestras ever gets old for him.

If despite all efforts the Bruckner symphony presents a challenge for ease of listening, no such accusation can be leveled against the work the Gewandhaus presented before intermission – the Violin Concerto in E minor by Felix Mendelssohn. The concerto was an immediate success when it was premiered by the Gewandhaus in 1845 (with Mendelssohn himself holding the position of Gewandhauskapellmeister, or musical director). It has been regularly performed ever since, and I predict it will be equally popular 100 years from now. Its gorgeously yearning opening theme is basically what the violin was invented for, and its perfectly balanced interplay between soloist and orchestra practically defines the “conversation” metaphor that is often attached to the concept of a concerto featuring any solo instrument with an orchestra.

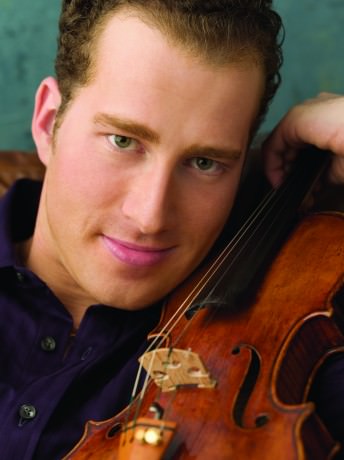

Yet in the hands of the extraordinary Danish-Israeli violinist Nikolaj Znaider collaborating with Maestro Chailly, the Mendelssohn received a fresh reading that mesmerized the Concert Hall audience. Despite its reputation for accessibility and balance, the Mendelssohn concerto is actually fiendishly difficult to play. On numerous occasions the violinist is called upon to repeatedly rock back and forth across all four strings in “arpeggios.” Often performers will simply and equally place all those notes while the orchestra rolls out a main melody. What Znaider did was to pulse the note of the bottom string on every occurrence, in the process revealing an internal countermelody that Mendelssohn had placed there.

Znaider’s attentive work on the violin’s low string throughout the concerto was especially significant given Mendelssohn’s continual return to virtuoso demands in the instrument’s highest ranges, typically expressed as a leap to find an exact note within the violin’s tiny physical gradations between one high note and another – a feat analogous to “sticking the landing” in Olympic gymnastics. It was perfectly executed by Znaider every time.

Znaider (think “Nicolai Snyder” and you basically have his name) also mastered the concerto’s demands for distinguishing between virtuoso work and Mendelssohn’s uncanny ability to turn a solo violin into an accompaniment to the rest of the orchestra. The early part of the concerto’s third movement resembles the Dance of the Reed Flutes from The Nutcracker Suite with a flute choir intertwining with the solo violin. Here Znaider did a masterful job of alternately taking the lead and relenting back to the flutes – even in one case varying his dynamics on a single held note to register the change. The ultimate reward was a palpable energy in the air from the audience during the concerto’s bravura cadenzas (extended, unaccompanied solo passages) during the first and last movements.

Washington Performing Arts is to be thanked for bringing the Gewandhaus Orchestra to The Kennedy Center.

Running Time: Two hours, with a 20-minute intermission.

The Gewandhaus Orchestra of Leipzig performed on Wednesday, November 5, 2014 at Washington Performing Arts (WPAS) performing at The Kennedy Center’s Concert Hall-2700 F Street NW, in Washington, DC. For future WPAS events, go to their calendar of events.

https://youtu.be/t_uA_W1wB5A