Clybourne Park, written by Bruce Norris in 2010 as sequel to Lorraine Hansberry’s 1959 A Raisin in the Sun, is a riveting play that focuses on race relations, America’s covenant-based housing bias, and the common man’s dreams for a better life. The Greenbelt Art Center’s production of this Pulitzer and Tony award-winning play is a worthy attempt to raise our consciousness on social issues but takes an unexpected spin-off from the play’s original intent giving a new edginess to an old conversation.

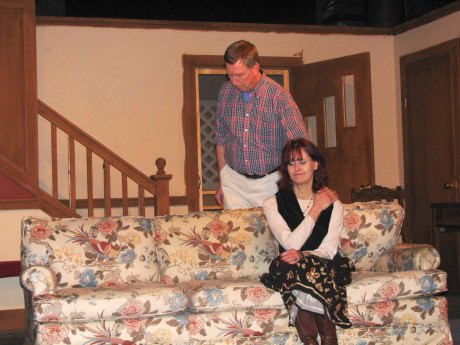

Taking up where A Raisin in the Sun left off, Act I is 1959 in the living room of Russ (Ted Culler) and Bev (Susan Harper) who’ve just sold their house to the first black family to buy a home in Clybourne Park, a suburb of Chicago. The opening energies in Act I are curmudgeonly slow, just like Russ, brilliantly portrayed by Ted Culler. A slightly-crazed Bev seems to get totally twisted in her underwear trying to get to the bottom of the derivation of the word “Neapolitan” as Russ sits in his easy chair slurping the creamy substance and going down the same slippery slope. The conversation finally ends up with Russ enlightening Bev on the depths of wisdom found in “National Geographic” by his naming the capital of Mongolia, Ulaanbaatar, much to Bev’s amazement and chagrin. It’s clear that Russ and Bev are suffering from some kind of weariness that has to do with their son’s death and a desire to improve their lives by leaving the home and its dark memories.

Karl Lindner (Jim Adams), a community association representative, come to visit Russ ad Bev and tries to persuade them to kill the deal so as to maintain the neighborhood’s property values. The household maid, Francine (Attey Harper) and her husband Albert (Ryan Willis) and Karl’s pregnant, deaf wife Betsy (Holly Trout) share the scene and do a fine job of anchoring the social mindset of the late 1950s along with Jim, the neighborhood priest played by David Colton, who adds a moral dimension to the discussion. Russ and Bev have their own beef with the neighborhood; however, stemming from its rejection of their son who committed suicide upstairs in the home after the community rejected him because of revelations about his military conduct during the Korean War. Jim Adams gives a strong performance as the race-baiting Karl Lindner but not until fairly late in the first act when the idea of discriminatory housing bias and resistance to racial integration finally come to the fore complete with profanity-laced arguing that almost comes to blows.

Sniggles and grins were a mainstay from the audience throughout the entire production and it felt like Director Bob Kleinberg and/or Producer Malca Giblin could not quite make up their minds if their version of Clybourne Park was meant to be a comedic drama or a serious follow-on play about race relations in America.

Act II takes place fifty years later in 2009 in the very same living room. The characters are all different but played by the same cast. The story line in the second act presents a heated encounter between a white couple who want to build a McMansion in what has now become a black neighborhood undergoing gentrification. The couple’s attorney, and several others who are somehow related to the characters in Act I, including Lena who is a descendant of the maid Francine and her husband Kevin, have come together to talk about the neighborhood’s housing codes and building restrictions to preserve the integrity of a neighborhood in transition. Disputatious fussiness between the characters is laced with people cussing and talking all over each and telling supposedly open-minded jokes about black folks who don’t ski, gays, and stuck-up white chicks, to add a bit of levity. But the back and forth bickering is over-the-top in contentiousness and lasts for what seems like an annoying eternity of pointless arguing and knockdown/drag-out animosity leading nowhere.

Themes pondering loss, death, change and human nature’s propensity to grapple repeatedly with the same issues; however, seem to dim the subject of race relations per se. In the “Director’s Notes,” Kleinberg believes that, “It did not matter when, or what the actual circumstance, we humans have basic patterns of behavior- love, aggression, protectiveness, anger, compassion – which appear over and over. However, for a play dealing with racial issues, I was disappointed that nowhere in the “Director’s Notes” is the word “race” even mentioned. In my opinion, this is where Clybourne Park spirals into a production that only faintly continues Lorraine Hansberry’s pressing colloquy on race in America.

John Decker’s living room set design of the small bungalow in Clybourne Park more than adequately makes good use of the GAC’s intimate black box theater, and Malca Giblin’s set decoration and dressing design adds just the right touch to create a mood of the 50s fast-forwarded to present day.

The words of Nat King Cole’s “Stardust” can be heard rising from an old-style radio box in the opening moments of Clybourne Park,

“You wander down the lane and far away

Leaving me a song that will not die.”

Clybourne Park takes the song to heart in evoking a sense that Hansberry’s original idea for a serious discussion on race is taken down a different albeit thought-provoking path to examine the forces of change that never change.

“It did not matter when, or what the actual circumstance, we humans have basic patterns of behavior- love, aggression, protectiveness, anger, compassion – which appear over and over.” – Bob Kleinberg

Running Time: Two hours and 20 minutes, plus one 15-minute intermission.

Clybourne Park plays through Saturday, February 21, 2015 at the Greenbelt Arts Center—123 Centerway, in Greenbelt, MD. For tickets, call (301) 441-8770, or purchase them online.