In The Power of Myth, Joseph Campbell writes: “The black moment is the moment when the real message of transformation is going to come. At the darkest moment comes the light.”

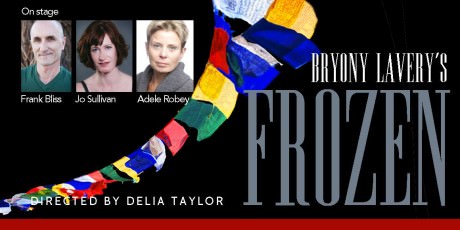

And, to be sure, in Bryony Lavery’s Frozen, now on stage at the Anacostia Playhouse, the darkness grows ever deeper, the light ever dimmer, as the potential for human agency shrinks and shrinks.

As the play’s Dr. Agnetha Gottmundsdottir quips:

I am a psychiatric explorer.

So my chosen expedition will be …

The Arctic sea that is …

the criminal brain

… her contention being that the serial killer’s brain is hardwired, fixed (or frozen as in an Arctic sea) in a perpetual renewal of murdering that which most offends.

The Anacostia Playhouse’s production of Lavery’s Frozen might not exude the unbearable rage and pain and terror that the brutal murder of a child elicits, but it is well worth a trip to an ever-changing Anacostia. As the story progresses, its three fine actors find their flow in the story’s raw tension, pulling the audience into its quest for understanding and forgiveness.

The story of Frozen is rooted in three intertwining ethical transgressions.

Jo Sullivan plays Dr. Gottmundsdottir, whom Lavery based on real life psychiatrist Dorothy Lewis and her study of serial killers. She has just had an affair with her fellow doctor, mentor, and associate. He is also the husband of her best friend. He has also just been killed in a car crash.

Sullivan’s portrayal of the doctor is crisp and icy and convincing — the character’s early panic attack not withstanding.

One of the subjects of Dr. Gottmundsdottir’s work is Ralph Wantage, played by Frank Bliss. Ralph rapes and murders little girls, and he has no remorse. He is currently serving a life sentence in a maximum security prison near London.

Bliss captures the killer’s explosiveness as well as his banality. I would have hoped for a bit more characterization of the pleasure Wantage derives from his murders, or what Georges Bataille refers to as the eroticism of death.

One of Ralph’s victims is the 10-year-old Rhona, the daughter of Nancy Shirley, played by Adele Robey. Nancy endures years with her daughter only missing, daily hoping she would walk through the front door and into her life again. After Ralph’s conviction and the recovery of her daughter’s remains, she must wrestle with her own suppressed rage.

Robey’s challenge is reflecting Nancy’s deep loss, sense of guilt, and eternal hatred for her daughter’s vanquisher over a twenty-year period. In the play’s early monologues, the dynamics of Robey’s character do not reveal even momentarily that powerful subtext, leaving her portrayal as somewhat one-dimensional. As the play progressed, however, she brought out Nancy’s struggle to come to terms with her daughter’s murder.

Delia Taylor directed Frozen, choosing an intimate alley staging of the action. She handles the transitions between scenes well and keeps the pace moving, but probably should have paid more attention to Nancy’s narrative arc. Also, her choice to de-emphasize place during most of the script’s monologues might have helped undermine their comprehension.

Taylor worked with a strong production team. Robbie Hayes created an effective minimalist set as well as the production’s use of real-time projection. Michelle Elwyn’s costumes were character building, and G. Ryan Smith’s lights dramatic, even those that flashed in my eyes during one early scene, forcing me to close them.

The process of becoming, that time honored idea first espoused by Heraclitus some 27 hundred years ago, seems too relentless even for neuroscience to stop. Or maybe it’s the brain itself, ever plastic, ever in need to optimize the individual’s experience of the world, that refuses to not promote eternal change.

In any event, even Frozen, which ironically asserts to the end the possibility that “becoming” might die a frosty, hardwired death, cannot resist the inevitable shift that empathy produces.

Such a shift makes “change” master over the human condition.

And if “the difference between a crime of evil and a crime of illness is the difference between a sin and a symptom, (by Malcolm Gladwell, but co-opted in Frozen),” then such a shift make the crime in Frozen a sin after all.

Running time: 90 minutes, without an intermission.

Frozen plays through March 1, 2015 at the Anacostia Playhouse – 2020 Shannon Place SE, in Washington, D.C. Tickets can be purchased at the door or by going online.

RATING: