John Stoltenberg: It’s great that Molly Smith, artistic director of Arena Stage, and Eric Schaeffer, artistic director of Signature Theater, have initiated what will become the Women’s Voices Theater Festival: Next September and October, more than 50 theaters in and around DC will present world premieres of plays by women. The vast majority of plays that get produced are written by men. So yes, of course.

But what of the voices of women in the parts men write?

Most of the great roles for women have been written by men—but so have some of the worst. I’m guessing female actors have some idea of what “worst” can mean. And probably female theatergoers as well.

So the question of how a man writes parts for women interests me.

“The simple truth is,” Aaron Posner told me, “writing male characters is easier for me. They are more easy for me to connect to personally. They come more quickly and more fluidly. Female characters require more thought, more conversation, more research.”

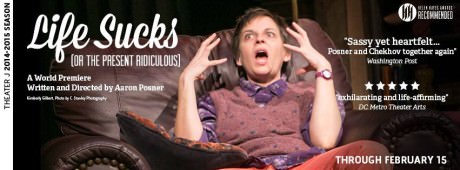

There was a lot about Posner’s new play, Life Sucks, that I admired. “One of the most exhilarating and life-affirming experiences in the theater you’re ever likely to have,” I said when I reviewed it. But what impressed me most was Posner’s handling of the women characters. I sensed something remarkable going on, something I wanted to find out more about. So three days after Life Sucks opened I talked with Posner, and a week later I talked with Judith Ingber (who plays Sonia) and Monica West (who plays Ella). What I learned about the offstage process of creating the women’s roles in Life Sucks was almost as fascinating as their performance onstage.

Aaron: During one of the first talkbacks I overheard a comment from somebody who called Life Sucks a feminist reimagining of Uncle Vanya—which I was surprised by and pleased by; I thought that was kind of wonderful.

That was the impression I left with, and that’s why I wanted to talk with you.

That’s great.

There are four women characters in Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya, and two of them, Yelena and Sonya, are the basis for similarly named characters in Life Sucks, Ella and Sonia. Yelena in Chekhov is a trophy wife. She’s sexually objectified and hit on by the men, and characterized by idleness and lack of interest in serious work. She sacrificed her music career to marry a cranky elderly pedant she does not love. And then there’s Sonia, who’s like a doormat domestic. She’s haplessly pining for a man who does not want her. She has zero self-esteem, no life of her own.

That’s what’s on the surface of the text. And though I couldn’t argue with the core of what you say, I think that any good production of the Chekhov play would know that you’d want to be looking for the opposites and the other energies in those characters as well. But your characterization is not inaccurate to what is in the text. And I believe that’s Chekhov dealing with the world that he was in and the people who were around him, and as the acute observer that he was, he was responding to what he was observing around him at the time.

You took those characters into the twenty-first century. How did you think about what you wanted to do with them? What was your intention?

There was no grand intention. Certainly I never thought of this as anything like a feminist retelling. I didn’t one day go, Oh this is what I’ll do, I’ll turn these characters on their heads. Like Chekhov—maybe the ballsiest sentence one can say, “Like Chekhov…”—I’m watching what’s around me. And I’m looking at the people I know, the people I see, the people I’m engaged by or I wonder about.

I sat down and talked to women. I had several conversations with several very attractive, very engaging women, and I had very frank conversations asking them specifically what that was like, and how they lived in the world in relation to the way that they are perceived by others, particularly by men. I just became interested in who those people would be today, or the women in those situations today.

In the first draft of this play you would find an Ella much more similar to Yelena in Chekhov. But I wasn’t satisfied with it, and neither was my extremely intelligent home dramaturg, my wife [Erin Weaver], or our excellent and strong set designer, Meghan Raham. I’ve been talking to smart, savvy, excellent women about this play for a year and more. We’ve been doing readings. And I’ve listened. And therefore the women characters have evolved, even from when we began rehearsals a month ago—who Ella is, who Sonia is, who all of the women are has continued to evolve and complexify, because I build not only from the research I’ve done and my own thoughts but also from the people I’m working with. Monica [West, who plays Ella] is in there, as is my wife, as are friends, as are women I’ve spoken to about this over the last year or two. So, it’s some big amalgam for me just trying to tell the truth of what I understand or am trying to understand.

There’s a long speech that Ella gives to the audience that begins:

Can I ask you all a question? How many of you would like to sleep with me if you could? I mean, hypothetically, if there were no rules, no issues of fidelity or morality… or even meta-theatricality… Just based on whatever it is you know about me right at this moment, can we get a show of hands…? How many of you would just… pretty much like to have sex with me?

After asking the audience several more such direct questions, she comes to her point:

As far as I can tell, we’re all just in a twisty, impossible, fucked up… yes, okay, perdurable miasma of “unmanageable urges” vs. “moral imperatives”, and instead of being able to just… connect… just be in a kind and loving communion with our fellow human beings, we’re forever wrapped up in this… sexual dance macabre… this ridiculous relational gavotte… this endless pursuit (and retreat) of unexpressed, unfulfilled, unexplored, unknowable needs and desires and frustrations and—

That speech seemed to come from the inside of Ella’s character, not a male view of her. It seemed to come from an inner experience. And your explanation that you talked to women about this in particular is kind of admirable and exemplary.

Well, thank you. That monologue came into the show two weeks ago or so. When we started rehearsals Ella had a different monologue, and the core of it was that she was actually five different women, and while people find her a certain way they’re all responding to different things and her own capacity to be different things for different people—which was a theme that had come up in a variety of conversations I had had with women. I loved that speech but it was a little more contemplative. The speech Ella has now was a more accurate way of getting at and catching more in the moment of her experience in the middle of the play.

There’s a point at which Ella asks the doctor, Astor, what attracts him to her, and he says, “Your contradictions.” When that line went by, I thought, That’s what typically turns men off about women. What are you doing there?

I think that thought crossed my mind thirty years ago or so, because of Jessica Lange in [the film] Tootsie. There’s nothing like universals, and what men find attractive or what turns men on is going to be far from unanimous. So I think for at least some proportion of men, that intrigue or complexity or not understanding is what engages them. To me Jessica Lange in Tootsie seemed kind of wildly hot but also incredibly sweet, totally strong but totally insecure, just full of contradiction. Most people aren’t one thing. But even if they are, that tends to be less interesting to us than people who are a bunch of things. And when those things are really at odds with each other, that can put some people off but it can also certainly engage.

Let’s talk about Sonia. She has that monologue where she’s expressing her sexual frustration and longing for the doctor:

…all I wanted to say [to him] was “please, please, please, take me upstairs right now, tear my stupid clothes off my stupid body with your teeth and fuck me so hard and so well and so long that that that… that the bed breaks, and the universe disappears, and the sun stops in its rotation to see what all the fuss is about and the world comes crashing to a stop and our epic, ridiculous, sublime love-making is the last thing that the universe ever knows.”

I don’t believe that’s in the Chekhov play. Tell me how that happened.

I have no idea.

But you made it up.

Yeah, I just made it up. The reality of my life, because I’m very busy and I have a three-year-old, is I’m the opposite of those writers who say, Oh yes I have a routine, I wake up at 7 a.m., I write till noon. That, which sounds so awesome to me, is the opposite of my life. So I often am writing from 1 to 2 a.m., I’m writing at 7 a.m. before my daughter wakes up, I write on planes and trains and in odd corners, and even within weeks I often look back and I have no memory of when I particularly wrote this thing or where it came from or whatever else.

The rewrites that happen in rehearsal I remember better, because I’m right in the process. But I have no idea when that Sonia thing came into it. But again, everything comes because you’ve had the experience or you’ve imagined the experience or you’ve talked to people about it. You know, the amount of shit that circles around our brains and hearts and spirits and minds—there’s so much in there, and so I start writing these things and stuff comes out.

There’s a counterpoint between Ella’s beauty and Sonia’s homeliness (as Sonia sees herself):

ELLA: You are lovely.

SONIA: No I’m not.

ELLA: You are.

SONIA: No I’m not.

ELLA: Sonia, you have beautiful

SONIA: Stop! I swear to God if you say eyes or hair I will cut your heart out with this swizzle stick!

ELLA: Ummm—

SONIA: We all know the code. You know your codes, what the glances and looks and little touches or whatever you get mean… you know sexy code, right?

ELLA: Umm…

SONIA: Right?!

ELLA: Yes, I guess so…

SONIA: Well I know ugly code.

Would you talk about that exchange?

Well, I do spend my life as an observer of human behavior, and it’s my job as the director. There’s some ridiculous statistic about 99 percent of communication is nonverbal. People are all speaking to each other in code constantly in and around the language that is being said. But most of the time people don’t acknowledge those codes. I think the truth is most people most of the time aren’t even aware of the codes that they are either sending or receiving. But the codes are all there, and I think we all know them on some level.

A significant portion of what I do is take what’s normally left in subtext, or what Chekhov certainly put in subtext, and I just force it out into the world in some way. I have people say those things, very much like in the Sonia monologue you were talking about. It’s just a matter of taking what usually stays in the mind and throwing it out onto the stage.

The dialog that you set up between a woman who is dealing with the down side of being beautiful and a woman who’s dealing with the down side of not being beautiful—it’s a conversation that has a self-evidentiary quality, like “Oh, of course, that is the interior of those lives coming through.”

The core of that conversation is in Chekhov—not the specifics but the idea of that encounter between the two of them comes from Uncle Vanya.

You’ve mentioned you were working from life, from women you’ve talked with and known. At the opening night reception you acknowledged and thanked your spouse, Erin Weaver. You had an acclaimed actress around while you were writing this. Would you say more about her influence on your treatment of the women characters in particular in this play?’

There’s two ways in which she’s influenced. Obviously she’s the person I share my life with and that I have grown from and I learn from about things all the time. We’ve been married for six years, together for a dozen years, and I learn from her every day, so she’s a deep influence on my thinking. We’re very, very different people, and therefore we’ve continued to learn from each other all the time. The other thing that happens to be true is she is about the best dramaturg I’ve ever met. I’ve worked with some great dramaturgs. But she is about the most insightful, clear-sighted, no-bullshit dramaturg one could ever want. She goes right to the point.

So here’s a true story: She came and saw the final dress rehearsal a week ago Tuesday. She pointed out a major problem with a scene that was in the play and the way it set things up. It was the second scene of the play, a long monologue by Vanya about where he was in his life. She pointed out to me in no uncertain terms that this was problematic in a variety of ways. I woke up the next morning. I wrote a new scene. We cut that other scene from the play. And we rehearsed that new scene on Wednesday afternoon and we put it into the show on book Wednesday night.

It’s not just that she’s a smart dramaturg. She’s also my dramaturg; she knows me better than anyone. She understands who I am and how I think and what it is I’m trying to do. I think she’d be a good dramaturg for anyone but she’s of course the ultimate dramaturg for me.

I sensed during the show there was a muse at your side, and that was before you mentioned her at the post-show reception, very generously as you did.

And it was the women in the cast who were a major influence. It was other women who have done readings. It’s my good friends like Holly Twyford and Kate Norris who I talked to about these things. It’s not all just Erin, but in all of my work she is an incredible help.

Because you not only wrote these roles but as the director cast the actors to play these women, I’m curious to know what you were looking for. And what did the actors playing those characters bring to the roles in rehearsal and in performance?

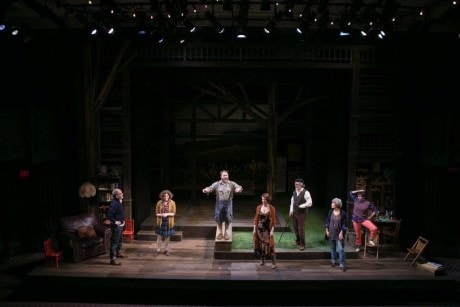

I always—whether I’m directing my own work or whether I’m directing Shakespeare or whatever the play is—I’m always interested in the ways that the actors inhabit and affect the characters that they’re playing. And the dialog between the actual actor and the character is an incredibly interesting one. So I believe in allowing them to inform each other and building from the actual people that we have. I’ve done half a dozen readings of this play over the years, and some of the actors I saw in some of those readings had an influence on me. The actors that I cast, I was looking for talent, I was looking for certain kinds of energies, but mostly I was looking for courage to tell the truth, capacity to tell the truth, and a kind of generosity of spirit that would lead them to be willing to take the risks to put it all out there on the stage. And I was very blessed with this cast.

There was no day of rehearsal that there were not rewrites, and that includes the final day of rehearsal, the day before we opened. There was no single rehearsal without rewrites—which is not what I told them when they signed on. They reminded me on the day before opening that we had done a reading about three months before we started rehearsals in which I said to them, You can probably start getting off book, because I think this is pretty much the script we’re going in with. And they were mercilessly making fun of me for that, because that was simply not the case.

We were rehearsing a play in four weeks, the normal rehearsal period, but it was a play that was being rewritten every day. That scene I mentioned came into the show on the Wednesday of first preview. There was another scene that I wrote on Friday that came into the show for the first time on Saturday—the scene with the sock puppets in the second act.

That was a great scene between Pickles and Ella. Pickles is just such a beautiful character.

Well, Kimberly [Gilbert] inhabits it so spectacularly. This was also my wife’s idea. The character in the Chekhov is of course [the laborer] Waffles. And as I drafted that and my wife read it, one of her responses was, Working people are always men. Why isn’t this a woman? And I thought about it for a long time and finally decided that she was right, and that’s when Waffles became Pickles.

Pickles’ speech where she’s talking about never falling out of love with people, and her longing for Iris, and how she expresses longing for Ella, is so sweet and deep and beautiful:

Fidelity is fidelity. It’s constancy. It’s a commitment and it’s to be honored, not mocked. Not mocked. You all make fun of me and I get it, I do, I guess I’m a little ridiculous, and maybe I’d make fun of me too if I were someone else, but I know about fidelity, and I…I gave her my heart. I gave her my whole heart and we made each other a vow and I have been true to that vow because Iris was the love of my…life and, yes, she left me seventeen years ago, and…everyone is always saying to me—move on. “It’s time to move on”…. But …I can’t “move on.” How can I? … I don’t know how you all…can just go from one lover to another to another to another, I don’t, not if that love is real. Not if it’s real. Love is love and it stays forever. I think. I think it stays forever.

While I certainly hope it’s a well-written speech, that is Miss Kimberly Gilbert in all of her outstandingness. You know the cliché of “You could hear a pin drop”? The way the audience engages with that speech and what Kimberly does with it, I find just stunning to watch.

For me it was the point when I felt the play deepening. It was like, this soufflé I’ve been watching has got meat and potatoes.

That’s right, that’s exactly the first time we drop it to that kind of level and try to set the playing field for what’s to come.

Is there anything on this theme that you would want known, by theatergoers or other writers?

It’s been very gratifying to hear the response. A young woman, a young actress who I just recently worked with, saw the show and afterwards she actually sort of smacked me on the arm and said, “How do you write women so well? How did you do that?” Like she didn’t expect it of me or something. I’m just trying to tell the truth as I understand it. The fact that it is hitting people, or landing with people well, is very gratifying. And I have big debts to pay to the people that we’ve talked about.

______

(A week later.)

John (to Judith Ingber): Tell me about the process of rehearsing and performing Sonia.

Judith: When I first saw the script I was really excited about the chance to tell a story about the intimate details of a woman who is so close to so many women in so many ways. I see movies and TV shows like Broad City and Girls touching on the realities of what sometimes happens in your life psychologically and emotionally. This touched on that too.

What was it about the character that you were first drawn to?

She’s in a situation people find themselves in, where you’re just obsessed with someone. Moving through that and finding out where your boundaries are, as a person, and what you think love is in your life, is something I relate to.

Did Sonia change during rehearsal?

The thing that changed the most for Sonia was finding her journey in the second half of the play. At the end of the play we all talk to Vanya trying to connect with him. “What, am I supposed to feel sorry for you?” is the name of that scene. The first preview, mine changed to what it is now, which is a really genuine confession and appeal. Before that it was more about my physical appearance: I’m not gonna change, I’m a frog. So when we changed that speech it helped me connect the dots to the journey at the end for me to say life doesn’t suck.

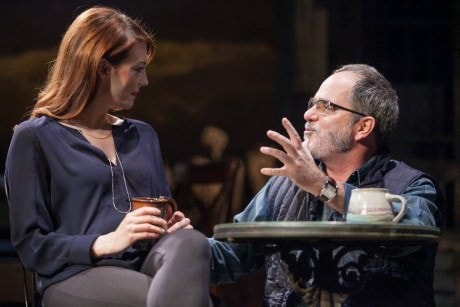

John (to Monica West): Tell me what you responded to in the character of Ella when you read the play and what it was like to rehearse.

Monica: Well, the character of Ella changed dramatically during the rehearsal process. I was drawn to working with Aaron in the first place because we had wanted to work with each other for a couple of years now, so that’s what drew me to the project. But then reading the script—Ella is a woman, a character, that I have not played before.

It was such a thrill to play a woman who has all of her thoughts very well formed at her fingertips. And although Vanya and Astor and maybe the Professor talk to her, possibly at her, she’s following them in every conversation, yet she is thinking about totally different things and returns to them with exactly what she’s thinking. I had a feeling that what we started with and what we ended with would be very different. And it was. And Aaron was so cool. He would ask me what I felt and he would listen. And it was incredible.

When Ella started she had some monologues that had to do with men and women in general. To me it didn’t feel specific enough to Ella. So then Aaron began to write things about the men who are talking to her in the play and about herself and love. He totally, totally changed the monologue. And it’s pretty daring, but I love it.

The monologue where you say, “How many of you would like to sleep with me…? ”

Yes. That used to be about I’m like five different women. I adapt myself to each situation. And we learn how to do that as women. So depending on who you are dealing with, you act a certain way with this person and that person. While that may be true, it’s less about Ella being different to other people and it’s more about how people perceive her. What’s different now, the way that Aaron has written this woman, is that she is telling people who she is. They might make a decision about what they think she’s like. But she is going to tell you what she is actually like.

Can we talk about that speech to the audience?

Yeah.

What has it been like to play that scene? What kind of reactions have you been getting?

It was really interesting when that came into the show, because Aaron wrote two or three different monologues for that point. And I read them all out loud. And again, so cool of him, he was like, Which one do you connect to? And I said this one. That’s the one that’s in the show.

And what’s so amazing about it is that, you know, I connected to it, but I’m so glad that I didn’t think about actually doing it in front of people. Because the first time I did, it I was like, Wow, this is pretty intense, to ask an audience, How many of you would like to sleep with me if you could?

In the rehearsal room we all try to help each other, so when someone asks a question in the play we answer it. I ask people to raise their hands, they raise their hands for me. But what I wasn’t expecting in the play was that some people would be embarrassed to do that. I certainly would. And Aaron addresses that in the script:

Now… You don’t have to raise your hands for this one, but…how many of you were lying? Either because of who you are here with, or how you want to be thought of in the world, or because of my feelings, or…

—which are all really well-thought-out things of why people wouldn’t raise their hand. But it’s really fun, because then he added the part:

And now another question… how many of you are currently dying to sleep with someone other than the person you should want to be sleeping with?

—which made it broader than just wanting to sleep with this actress who’s on stage or the character that’s on stage.

You know how people talk about the brilliance of a comedian who takes everyday things that we think about and then puts it out on stage, and that’s why we all laugh, ’cause we’re like, Oh my god, I’ve been thinking that in my head for so long—but someone brings it to the public? Aaron does that. This is stuff that we think about all the time. Even if you are a faithful person in your relationship, everybody thinks about this stuff. And you would be lying to say that you wouldn’t.

Judith: I have friends who came and saw the show and they just love talking about that speech, because that’s when you’re really communal, like, I’m with all of these people. I mean you don’t really think about being in an audience with all of these people as much when you see a lot of shows. You know, you laugh when other people laugh sometimes. But like, they raised their hands at a certain moment and they’re the only people who raise their hands, and everyone looked at them, and they were like, Oh my god. But they’re also thrilling to that. They loved it.

Monica (to Judith): What’s it like to do your monologue?

The one where Sonia’s declaring her desire for the doctor?

Monica: Yeah.

Judith: For that monologue, for me, I can’t see the audience very well at all. Which is not necessarily a bad thing ’cause I’m in sort of a zone of my own. Say you have a crush on someone and then you say something stupid and you have these private moments of like wughgh. That’s what’s really fun about that monologue. It’s like this very private moment of I wanna fuck oh my god, but you get to say it. And it’s so funny to hear the different audiences’ reactions to it, and to feel their energy changing and shifting. Then when it kind of denouements to a more painful place, to hear people go, Oh, oh god. I love those little things that are so universal.

One of the things that jumped out at me from these monologues was how authentic they seemed to a woman’s experience. They weren’t framed through a male lens of an idea of what a woman who is sexually attractive should be acting like or what a woman who is sexually desirous should be like. There’s no cheesy framing of these as archetypes of male imagination trotted out one more time. It was just not the typical way the male gaze would portray women who have that to say. It was really women having that to say.

Monica: I think you’re right. One of Aaron’s many gifts is he is an incredible listener. He listens to his actors; he listens to his wife, who I think was integral in developing Ella. But also, where some playwrights may love their idea of women—or of how they want to experience them, or wish they would be—I think that Aaron loves women for who they really are. He loves women for real and not an idea of them. All different kinds. He doesn’t narrow it down to the perfect type woman.

Judith: And he asks questions. Like he’ll say, As a man, when I’m obsessed with someone I feel this way about this person—is that the same for women? He will ask, Are you connecting to this? Which is great. Because you don’t get to have that confirmation, especially with so many plays where I’m frustrated reading them.

Monica: If another prostitute is written in a play—

Judith: Or just another innocent—another innocent who just doesn’t get it. Like: no. I can be innocent and smart.

Monica: Yeah, that’s what’s great about this play.

Judith: At the beginning of rehearsal he asked us to be the smartest we can be. Smart as actors and as characters. And that’s really great.

I want to ask you about the scene between the two of you about the sexy code and the ugly code. Tell me what it was for you.

Monica: Some scenes, it’s a very clear path to find the different tempos, is it staccato, legato, whatever. But this one was hard—

Judith: It was really hard.

Monica: —to find the rhythm of it.

Judith: Yeah.

Monica: And once we did, that’s when we started having so much fun. It’s my favorite, favorite scene to do in the show.

Judith: We’re totally on the same page with that scene. I love that I’m given a chance to be the most stark and the most naked with her, the person who I would want to be the least naked with. And I love the two different realities of the characters, how they both squash different parts of themselves or lift different parts of themselves up in certain ways, and how that mixes into this fun scene of a real girl talk.

And the audience is allowed to eavesdrop on this very intimate scene that goes to the core of something that’s such a universal about appearance in women’s lives.

Judith: Yeah. You don’t talk about that—

Monica: In the way that we do.

Judith: —in the way that we do. Even, like, a friend, you don’t want to hurt them, you don’t want to be like, Well you’re right, your nose is really big. You don’t say that, because you feel like you’re saving them from something. But they look in the mirror every day and they think this. So how is that helping? It’s a really interesting topic. It’s really churning, like gut churning.

Monica: I love the way Aaron directed us as well because, like, he saw that Judith and I hit it off, and he was like, Bring all like the weird things that you guys do to the scene. And for me, with all the men in the show I’m on guard in a certain way, because I do have to defend myself and tell them who I am. But this is the one scene where my guard is down.

Judith: Yeah.

Monica: I don’t think we’re playing a game—

Judith: No.

Monica: —we’re really trying to connect, and we miss.

Judith: Yeah.

Monica: We really try to connect.

Judith: What I love about the scene is the level of trust that actually does happen, and the want for trust, the want for a confidante. I love the need for friendship in the scene on both sides.

Life Sucks plays through February 15, 2015 at Theater J at The Washington DCJCC’s Aaron & Cecile Goldman Theater – 1529 16th Street, NW, (16th and Q Streets), in Washington, DC. For tickets, call the box office at (800) 494-8497, or purchase them online.