You’d be hard pressed to find a better theatrical catharsis for high school angst than Dog Sees God, Bert V. Royal’s funny/poignant reimagining of characters from the Peanuts comic strip playing this weekend in an entertaining/moving student production at George Washington University. Directed with sharp sensitivity by Elizabeth Kitsos-Kang, the show is both a send-up of adolescent superficiality and a serious look at teenage bigotry, the kind that makes picked-on kids want to kill themselves. It’s like a lifesaving lesson wrapped in laughs.

The play, which premiered off Broadway in 2005, predated Glee by four years and presaged the television hit’s uncompromising look at high school bullying driven by animus and anxieties around appearance and sexual identity. Royal is openly gay, and though his script is loaded with broad humor, it minces no words about the tragic consequences of teenage intolerance. GLAAD recognized the popular play with a media award, and Royal has a sequel in the works.

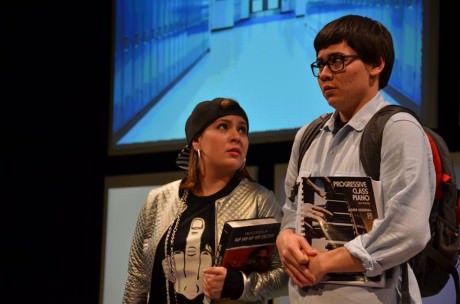

Dog Sees God, which follows the Peanuts gang into high school, skirts copyright issues by altering the characters’ names and calling itself an “unauthorized parody”—the object of the parody being not the comic strip but high school life. The title comes from a line spoken by Beethoven née Schroeder now a gay kid who practices piano privately during lunch period to avoid being bullied in the cafeteria (Nick Ong plays him with affecting timidity and tremulousness). “You know they say a dog sees God in his master. A cat looks in the mirror,” he tells CB née Charlie Brown (played with appealing agility by Jon Weigell), who is mourning his dead dog and harboring a boycrush on Beethoven. “I hate cats,” CB chuckles. He then abruptly kisses Beethoven full on the lips.

The moment came as a complete surprise not only to Beethoven on stage but to the opening night audience in the auditorium, most of whom were GW students and agemates of the cast. Their very audible reaction ranged from aghast shock to affirmational delight; it was an amazing interplay of performance and response. And it was in that instant I understood what I had been sensing was so engaging about this production.

There was something about the performances I had been trying to put my finger on. The cast members seemed to have thrown themselves into their portrayals with an energy, conviction, and physicality that seemed to go beyond thespian; it was more like therapeutic. Here were eight college students enacting not only for an audience of peers but for themselves some of the rawest, raunchiest, and rudest aspects of a life experience they had all shared but years ago. And they were celebrating in shared comic catharsis the fact that they had come through, they had survived, and it had gotten better.

Shane Moran, for instance, in a commendable performance as Matt (the former Pig-Pen, now a germophobe jock), gave the character a hilarious horny swagger plus a dangerous homophobic edge that was revealed to mask his own conflicted sexual feelings for the boy he beat up on. He was like an embodied Everydude, except his cool cruel exterior was anatomized before our eyes.

And Annie Ottati, in a noteworthy performance as Tricia (the former Peppermint Patty), skillfully rendered in entertaining detail—in catty cahoots with Samantha Gonzalez as Marcy (Marcie)—all that is fatuous and vicious in what passes for pretty and popular. In the interaction of stage action and audience reaction, something about the way the art of theater can show the interior of characters’ exterior seemed to be serving a collectively retrospective healing through humor and heartache.

The evening’s comedy peaked in Madison Awalt’s solo scene as CB’s Sister (Sally), who performed her one-woman-show “about a caterpillar who longs to evolve into a platypus instead of a butterfly” as a hilariously dreadful dance that had the audience howling. The audience also enjoyed the agreeably recognizable spaciness of Gregory Langstine’s performance as the slacker pothead Van (Linus). As it happens he smoked the ashes of his blanket after it was burned by the pyromaniac Van’s Sister (Lucy), performed as amusingly deranged by Liena Rose Armonies-Assalone.

Costume Designer Sigríður Jóhannesdóttir has captured exactly the clothing tastes of this quirky cast of characters. Lighting/Scenic Designer Molly Hall has given the stage a Mondrian-like comic strip look with pastel panels in black margins, while her projected cartoonlike illustrations indicate scene changes wittily. And Sound Designer Austin Keefe has separated scenes with eloquent passages played on piano.

The pace of the performance started slowly, which may have been opening night jitters. The timing of actors’ lines was at first overhesitant, as if seeking an unsure split second too long the emotion to be played. Audience response seemed uncertain as well. Before long the production hit its comedic stride more confidently, and actors and audience connected with not only the authenticity of the material but also the wholehearted personal investment of the performances. In a curious way, the show began with the same undertone of “Will you like me? Will you accept me?” anxiety that everyone remembers vividly if not painfully from high school. The form was also the content. Here was a show about teenagers fearfully seeking acceptance performed by collegians opening themselves warily to friends and classmates. And what happened next was quite thrilling. Because once acceptance was signaled by an appreciative audience and once the actors relaxed into being fully present, Dog Sees God became one of those wonderful experiences in theater when candor is embraced and an audience is touched and lifted up.

Running Time: 2 hours 15 minutes, including one 15-minute intermission.

Dog Sees God: Confessions of a Teenage Blockhead plays through this Sunday, March 29, 2015, at The George Washington University’s Dorothy Betts Marvin Theatre, in the Marvin Center – 800 21st Street, in Washington, DC. For tickets, buy them at the Dorothy Betts Marvin Theatre’s box office, or call (202) 994-0995, or purchase them online.