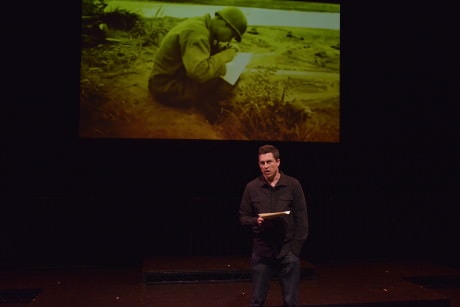

Fitting that If All the Sky Were Paper — a dramatization of war correspondence lovingly presented by archivist Andrew Carroll — would unfold at The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, a stone’s throw from the Smithsonian.

The work, produced by Victoria Morris of Lexikat Artists in association with Chapman University, is part artifact and performance art — fodder for museum hounds and bleeding hearts alike. Which is not to say it comes packing a political agenda or is coarse in its diorama of words relayed under duress.

Carroll’s mission: to scour the world for wartime screeds, traveling to 40 countries across six continents – sometimes in precarious, perilous situations – collecting over 60,000 letters. Some discoveries were as random and unlikely as a message in a bottle. Others were quite famously plucked from the foot of the Vietnam Veterans “Wall” Memorial.

Director John Benitz and Carroll manage to weave a bunting that knows no nationality or name, despite each letter being personally signed – “Fred,” “Goldie,’ “John,” “Mum.” The actors stand, sometimes alone or in formation, holding their “letters,” pieces of paper that carry the weight of the world. They recite testimony of soldiers, civilians, orphans, prisoners – crisp commentary on conflicts from the Civil War to Desert Shield to the present day. But they’re all jumbled up, out of order, spanning borders. The echoed emotions unify everyone who has marched to the beat of the drum, no matter the uniform.

If that sounds at all dull, consider: These aren’t speeches infused with rhetoric or navel-gazing journal entries dripped in woe and worry. Given that any letter has a built-in target audience, the intended recipient, the drama is built in. The play’s text is audience-ready; it’s both unfiltered (real) and filtered by the letter writer to calm, enlighten or connect with a loved one. A hologram of hope.

Carroll, with his expert editing, hits the target almost consistently. Using a stand-in narrator (himself, played by Garrett Schweighauser), he takes us on a hazy journey, like the Ghost of Christmas Past, letting us glimpse the enormity of war. “Enormity” in its dictionary definition – anti-morality on an extreme scale – as opposed to what people think it means (simply, “enormous,” which it does not). What’s enormous is the size of the task Carroll undertook in culling this material.

There’s not a lot of action in the theatrical sense, but the play is a window into the “action” seen and felt by history’s heroes, both on the front lines and reading between the lines.

Behind Schweighauser and the cast are projections that are exhibit-worthy, illustrative but at times veer into motivational-seminar, PowerPoint territory. The device is used most effectively when a litany of battles and death tolls flash onscreen, first readable but eventually blurring one into the next with the ferocity of machine-gun fire or warp-speed time travel.

Peppered in the cast are notable names: Jason Hall, the Hollywood handsome screenwriter of last year’s Oscar-winning American Sniper; Michael Conner Humphreys, an Army veteran who played young Forrest Gump in that iconically American film; and Scott Simon, of NPR and its StoryCorps’ Military Voices segment. A wealth of female voices, amplified by actresses whose talents prove the most affecting, and a Colonel Sanders-type character actor who does the sage bits, helps keep the experience democratically balanced. From the pockmarked-teen’s introduction to killing to the inevitable scarred battlefields and psyches, all are presented and accounted for. Their raw words are so alive, even speaking to us from the grave – so in contrast to the gloomy telegram that grieving families typically receive, which goes without saying.

I attended on opening night with a military reporter, who saluted the creative team’s ability to mute any ideological undertow. A few technological glitches could be forgiven, as the cast and crew had assembled for just one rehearsal earlier in the day. During a post-performance talk-back, in which Carroll clutched his portfolio of a few prized sheet-protected letters like a nuclear football, one of the actual letter writers piped up from the audience: Mark Rickert, who was an Army sergeant with the 372nd Mobile Affairs Department during the 2003 Iraq invasion. His letter articulated horrors witnessed at the hands of the “good guys” and debriefings packed in jars like a killer’s preserved trophies.

A veterans group recently publicly complained that most military figures portrayed in popular culture are of two myopic types: bloodthirsty war machines or PTSD-synched time bombs. What’s refreshing about this Memorial Day-timed inquest is its holistic viewpoint — not just from an American archetypal grunt perspective but that of our morphing enemies, allies and frenemies. Picture all those flags lined up, neat ornaments for tidy cross-marked graves, evoking the orderly lines of troops in government-issue dress, indistinguishable – but in stark symbolic contrast to our foes’ uniforms, colors and flags. Carroll and Benitz seem to drive home the message that, on the contrary, war is messy and the starkness is our similarity with our “enemies.” Message received.

This work is not The Diary of Anne Frank or Slaughter-House Five, but it blends the experience of each – especially one compelling tangent in the reading of a letter by Kurt Vonnegut Jr. as he assessed the fate of Dresden, Germany – once a “garden city” that was firebombed to smithereens by the U.S. and U.K. near the end of WWII. What a treasure to unearth what seems a preamble to his classic war novel, complete with a photo of the young author. Another focuses on our quintessential rival, the Russkies, and melts our coldest war myths.

We tend to romanticize long-ago wars as gentlemanly or even civilized, glossing over the brutality that rides shotgun and the secret inner conflicts that otherwise go unspoken.

If All the Sky Were Paper says loudly what needs to be said. It explodes with humanity – humor, dread, pride, wisdom — and finally reverberates as an anthem for peace. If war is hell, this show is a little slice of heaven.

Running Time: About 90 minutes, with no intermission.

If All the Sky Were Paper plays through tonight May 22, 2015, at The Kennedy Center’s Terrace Theater – 2700 F Street, in Washington, D.C. For upcoming events, go to its performance calendar.

This was a fantastic show. I hope it can get a longer run here in the future. My Uncle Bill’s last 4 letters he wrote to my grandparents before he was killed in France in Sept 1944 are now part of the collection.

This is a captivating and educating experience, presenting the horrors of war in a very personal way. The author Andy Carroll actually risked his life to embark on his global journey in search of letters that would personalize and humanize war and its impact on those directly in it and the many more on the fringes of it – especially those close to the combatants and suffering the impact of war by losing those closest to them forever.

At the same time it presents humorous moments and acts of great kindness not only to friends but occasionally to enemies. It shows the scars that the combatants took with them throughout the balance of their life journey, often unspoken for decades, if ever.

Finally, it presents a view of hope and understanding and promise, that making can move beyond the slaughter of war to a better place, forgiving their mortal enemies from the battlefield. One particularly touching moment is when a Japanese woman, who towards the end of World War Two participated in attaching explosives to balloons and launching the balloons into the jet stream to find their way to the US mainland, is devastated to learn years later that the balloons indeed came to the US and one was found by a group of children who had the munitions explode, killing them all. That long-range and long-dated impact of war was an ending piece to the play, emphasizing the hope for a better day among nations and their people.

A tour de force, this play needs to be on national display and available to all of us, young and old, to point to a better way for nations and individuals to get along, without war and with understanding and consideration. Tom Davidson senior