The authenticity and specificity of Katie Sullivan’s scenic and properties design for One in the Chamber could qualify it as a character in this engrossing new play by Marja-Lewis Ryan. Even before we meet the people whose lived-in dining room this is, we can see from the memorabilia and clutter—family photos in mismatched frames on the wall, tattered board games in a pile, a jar of peanut butter and loaf of bread amid laundry strewn upon the table—that this is a household where togetherness has transpired.

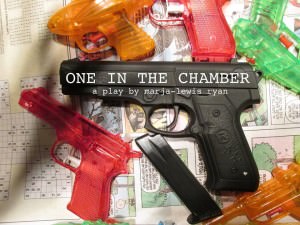

What we do not know yet is how that togetherness has been ruptured, and how each family member has been injured, by the death of a 9-year-old son six years ago when his then-10-year-old brother accidentally shot him with a gun.

Playwright Ryan has crafted the compelling narrative of this wounded, unraveling family in the form of a series of one-on-one interviews by a social worker who arrives to determine whether the surviving brother, now 16, can be let off parole. And Director Michael R. Piazza has deftly paced and shaped the family’s gradual undoing as sad and troubling disclosures steadily pile on.

A vividly imagined portrait of a family coping with the loss of a child in a gun accident, One in the Chamber is every bit the equal of David Lindsay-Abaire’s Rabbit Hole (which turned on the loss of a child in an auto accident) in making palpable through powerful theater the ineluctable presence of absence. And just as Rabbit Hole was not some tract about driver-safety education, One in the Chamber stands on its own as a play whose credibility and emotional impact derive from what happens before our eyes and hearts on stage—not policy disputes off.

This backgrounder appears on the production website:

- This play was inspired by the September 28th, 2013 article in The New York Times: Children and Guns, the Hidden Toll, which explored the rates of gun related homicides versus accidental shootings in America. According to a study cited in the The New York Times article, when 64 boys were let into a room with an inoperative .38 caliber hand gun concealed in a drawer, 2/3 handled it, 1/3 pulled the trigger and only 1 actually told an adult and he was later teased by his peers. Moreover, every day, 32 Americans are murdered with guns and 51 people kill themselves with a firearm (Brady Campaign Website).

- All of these numbers represent millions of families who have been impacted by gun deaths.

Then right away comes this curious disclaimer:

- This play is not political in nature, but rather, is a fictionalized account of how one of these families managed after their loss.

Presumably this is meant to avert audience expectations of arguments pro or con gun control. (There are none as such, though a robust series of post-show events promises much expertise and lively discussion on the issue.) Yet like all good and engaging drama—or at least the kind I go to the theater for—One in the Chamber is very much and implicitly political.

In Adrienne Nelson’s nuanced performance of Helen, we see the chilling character arc of a really good mom, a super-accomplished homemaker, utterly losing it over this loss. In Dwight Tolar’s stolid performance of Charles, we see a really good dad, a hardworking breadwinner and Army Reservist, unable to hold together the family he loves. In Grace Doughty’s adorable performance of seven-year-old Ruthie, we see a child escaping family tension into a fantasy world. In Danielle Bourgeois’ captivating performance of 17-year-old Kaylee, we see a big sister fleeing the pain of her broken family in alcohol and promiscuity. And in Noah Chiet’s extraordinarily moving performance of 16-year-old Adam, the boy who killed his brother, we see a tortured soul suffering unbearable guilt. Completing the well-chosen cast, Liz Osborn as Jennifer the social worker shows us someone whose professional objectivity falters then cracks.

The narrative device of the social worker interviews, once the playwright has set it up, can make the play seem somewhat labored. We learn early on that Jennifer will have a scene with each of the family members and that Adam will come last, making the action feel formulaic. This locked-in structure means that a scene I would really like to have seen, one between Adam and Kaylee, did not and perhaps cannot happen. Also, the play’s multiple conflicts—within the family and between the family and the judicial system—sometimes feel trumped up and don’t quite cohere. (This is probably a play that would work better adapted for film.) Yet as the haunting back story of a tragic gun accident is revealed one stunning detail after another, and as we come to understand more and more how one single accidental bullet also ricocheted and caromed around a family, we cannot help but feel devastated.

One in the Chamber is a true modern tragedy, epic in its implications.

Running Time: 75 minutes, with no intermission.

One in the Chamber plays through September 6, 2015 at The Mead Theatre Lab at Flashpoint – 916 G Street, NW, in Washington DC. For tickets, purchase them online.

Perhaps inadvertently, this review slighted one of the most stunning performances: by Liz Osborn. This LA film actress inhabits the subtle, reserved but complex character of social worker Jennifer so organically and with such fine, layered detail that one might easily overlook the mastery required to achieve that level of realism and restraint. She makes it look easy. Her film experience is especially effective in this small space, where every nuance of expression or energy change is almost palpable. Fortunately for us, Ms. Osborn is now “local.” I hope to see much more of her work.

Thanks to a strong script and several strong performances, even in my front/center seat (rarely more than a few feet from the actors), I frequently forgot I was watching a play. The well-constructed script rewards patience. Seemingly “odd” lines/actions eventually become painfully significant. E.g., the mother’s almost thrown-away “We don’t do group.” The explanation, when it comes much later, is wrenching.

Especially after praising the script as “every bit the equal of Rabbit Hole,” John’s subsequently describing this as “labored, formulaic, the conflicts trumped up and don’t quite cohere” was startling and perplexing. Part of the brilliance of Chamber’s structure is that it avoids inundating us with front-loaded explication of this complex situation. It flows deceptively easily while relentlessly pulling us in deeper as it unfolds. John’s suggesting “a scene I would really like to have seen” reveals one of the challenges for a playwright judging another. Though his scene could have worked in another construct, it would have been jarringly out of place in this one. A script should be judged according to the effectiveness of its playwright’s vision, not whether it matches the version the reviewer would have written. Different is not necessarily lesser.

Again self-contradicting his harsh description, John’s closing sentence seems to affirm that the script actually was effective, even for him. The rest of the audience at my (and his) viewing clearly deemed it so. They were “pin-drop” still throughout, except for appropriate laughs, gasps and “jumps.” Many viewers, including me, needed to decompress afterward. There were many sobs. Red eyes/noses were prevalent.

I’m wary of overselling it; it’s not a blockbuster. But the LA production’s accolades were well-earned, and it definitely SHOULD be seen. I thank Ms. Osborn, the Armstrongs, et al, for giving us the opportunity. Disclaimer: I have NO connection to the production or anyone involved, other than as an appreciative member of the theatre community

Though One in the Chamber for me came up a half-star short of five, I heartily agree that this production should be seen, which I trust my review made clear. Thanks for commenting, Karen!