There comes a moment early in Act One when Raymond, a young man who left his family in Rwanda to learn film making at NYU, returns to his homeland, which has become a devastation. The 100-day Hutu genocide of his people, the Tutsi, has exterminated his entire family, among a million more. Raymond—played with a beautiful power by Desmond Bing—stands downstage facing us the audience but looking as if at the evidence of a crime against humanity from which the world averted its eyes.

And seeing what he sees, he weeps.

In that moment could be witnessed the raison d’être for this epic and mesmerizing production: to permit us to see, through the lives and eyes of believable characters—both fictional and historical—a glimpse at the 1993 massacre in Africa that the world disgracefully ignored.

“It happened over. And over. And over,” a character says. “Five times more efficient than the Holocaust.”

Raymond decides to make a film to try to tell the complex story in multiple interconnecting and overlapping stories. But “how do you even begin to describe a genocide?,” he asks. “It is like trying to describe the sea to someone who has never seen it by showing them a handful of water.”

Boldly chosen to inaugurate Mosaic Theater Company, Unexplored Interior by Jay O. Sanders does more than offer a handful of water; it positions Mosaic as the preeminent theatrical platform for such necessary art. I cannot imagine another local theater-producing organization daring to attempt to tell a compact, conscientious, and compelling story drawn from the incomprehensibly sprawling Rwanda genocide.

Mosaic dared. And Mosaic did.

Sanders’s tightly crafted script is indelibly filmic in keeping with its main character’s POV. There are quick cuts within scenes and jump cuts between. Briefly sketched narratives overlap and abut. Characters from different realms appear onstage together—real ones with remembered ones, contemporary with historical, actual with fictional. Time shifts and toggles back and forth. And Director Derek Goldman master-manages this all with auteurial assurance.

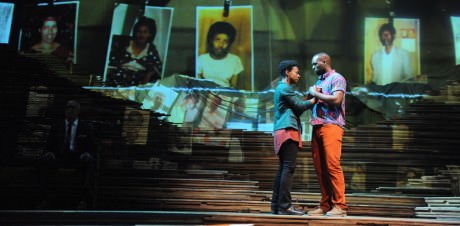

Meanwhile spectacularly cinematic effects lavish the stage: A constantly eye-popping panoply of projections (designed by Jared Mezzocchi) plays on a jumbo screen. Movie-theater-like surround sound (designed by Christopher Baine) fills our ears—from classical music to rainstorms to explosions and thunderclaps accompanied by striking lightning (lighting design by Harold F. Burgess II). The set (designed by Luciana Stecconi), constructed of ragged, rough-hewn wood layers and draped canvas, suggests the hillsides and fields of Rwanda with a fine lack of literalness that allows for multiple scenes set elsewhere as well.

Sanders, an accomplished actor, writes the kind of script that implicitly trusts actors unconditionally. He knows what need not be in words, and exactly what text cuts to the quick. Accustomed to hearing more prolix playwrights spell out more, I needed a scene or so to pick up on Sanders’ linguistic succinctness and quicksilver references (a lot of which are to flicks). But once I caught on, the result was heightened alertness to what the actors were doing.

The Unexplored Interior cast was astounding; each and every one commanded attention. And because the majority of the characters are African, there was a range and depth of roles and performances that mainstream theater rarely provides.

Bill Grimmette appeared as Felicien, Raymond’s beloved grandfather whose storytelling inspired Raymond to tell stories through film. Grimmette’s sage presence had enormous gravity.

Jeff Allin played Alan, Raymond’s film-school professor, mentor, and friend; then doubled as General Romeo Dallaire, the real-life Canadian peacekeeping officer who tried to avert the genocide but got no resources to do so. Allin conveyed the complexity of both men’s stricken consciences with deep grace.

Erika Rose was Kate, Alan’s wife then widow, a film editor who accompanies Raymond on his journey to make his film. (“I’ve been African-American,” Kate tells Raymond. “But what do I really know about Africa?” “We are family, Kate,” he replies.) Once they get to Rwanda, Kate and Raymond set up and frame scenes as if directing Raymond’s unspooling screenplay, and Rose brought touching strength and verve to the role.

Isaiah Mays, a seventh-grader, played Boy, a nonspeaking role performed completely in dance and mime. Mays’s portrayal was every bit the peer of the other pros on stage, and his entrance dance (the show’s choreography was by Vincent E. Thomas) was a crowd-pleaser.

The Rwandan genocide had its roots in historical animus between the Hutu and the Tutsi, a racialist division—largely the residue of European rule (first Germans then Belgians)—that turned lethal when the majority Hutu set about slaughtering the Tutsi for ethnic supremacy. The news was met by ignorance and incomprehension abroad, plus much smug “they’re not like us” disdain.

The dramatist Sanders echoes what Shakespeare did with the Montagues and Capulets: He sets up two significant relationships in the play between a Hutu and a Tutsi character.

Raymond is Tutsi and his best friend, Alphonse, is Hutu. Freddie Bennett plays Alphonse with appealing energy and—as we learn when Raymond visits him in jail—very moving sensitivity.

Cat-reen is also a friend of Raymond’s from childhood, also Tutsi, and Shannon Dorsey plays her with sensuality and fierceness. As it happens Cat-reen and Thomas fall in love. And Thomas is not only Hutu; he is an aristocrat and government minister responsible for carrying out the slaughter of the Tutsi. In one of the play’s most engrossing twists, Thomas persuades himself that the more zealous he is in that genocidal pursuit, the more he will be able to shield Cat-reen from harm. His character’s “deal with the devil” makes for a quagmire of internal contradiction, and Michael Anthony Williams’s portrayal of him is intense.

Also contributing to the superb cast’s vivid storytelling were Silas Gordon Brigham, JaBen A. Early, Christian R. Gibbs, Jefferson A. Russell, and Baakari Wilder.

Sanders has inserted yet another telling theatrical device: He introduces the character of Mark Twain, the writer who is remembered and celebrated as a humorist but forgotten as a clarion of conscience. The real-life Twain, in a play called King Leopold’s Soliloquy, tried to tell the world what Leopold II did in the Belgian Congo. (“As bad as Hitler,” Kate says. “Killed ten million people,” Alan says. “No one cared ’cause it’s ten million BLACK people.”) In Unexplored Interior Twain shows up, his avuncular self in a white suit, to impart courage to General Romeo Dallaire:

MARK TWAIN: Watched your African adventure from the best seat in the house. Infuriated me all over again—did my best to sound the alarm, but they don’t seem to have learned a damn thing—human race just keeps movin’ in circles! Came here to persuade you to stay the course, sir. A man of conscience is a precious commodity….

DALLAIRE: …I thought you wrote comedies.

MARK TWAIN: When I learned about the horrors of Leopold and the Belgian Congo, sir, damn well drained the comedy right outta me. And same as you—tried like hell to arouse the world’s attention…

It is one of those marvelous trans-historical meetings of figures from different eras that can only happen persuasively on stage, and John Lescault brings Twain to life with an inspiring luminance that precisely brings the importance of the play home.

Unexplored Interior intersects community and conscience with sweeping scope and compassion, the likes of which this town needs more than it knows. So welcome to DC, Mosaic Theater Company! What a meaningful and momentous gift you bring.

Running Time: Two hours and 30 minutes, with one 20-minute intermission.

Unexplored Interior (This Is Rwanda: The Beginning and End of the Earth) plays through November 29, 2015, at Mosaic Theater Company of DC performing at Atlas Performing Arts Center – 1333 H Street NE, in Washington, D.C. For tickets, call the box office at (202) 399-7993 ext. 2, or purchase them online.