The operas of early 19th century master Gioachino Rossini play a big part in the life of Maestro Antony Walker. The artistic director of Washington Concert Opera is preparing for the company’s performance this coming Sunday of one of Rossini’s biggest but least performed operas, a musical feast about Babylonian times called Semiramide. Not long after that he heads to New York to prepare for the mid-December opening of the Metropolitan Opera’s production of Rossini’s The Barber of Seville in a family-oriented holiday version that he’s conducting.

What gets Maestro Walker these honors is a global engagement not only with opera but also the sweep of musical history and performance history. He’s a trained singer himself – no jokes from his musicians that he “sings like a conductor”! And his studies of the historical styles of baroque, classical and “bel canto” opera include performances and recordings by a period-instrument orchestra and chamber choir in his native Australia as well as staged productions by his Australian opera company.

As if to top it off, I actually reached him last week by phone in Pittsburgh, where he was in the middle of a run of Mozart’s comic opera Cosi fan tutte at yet another of the companies he conducts, the Pittsburgh Opera. Here are excerpts of our conversation:

David Rohde: Tell me about Washington Concert Opera, how old it is, and what the appeal of it is.

Maestro Antony Walker: Washington Concert Opera is 29 years old, and this is my 14th season. So I’ve been around for virtually half its existence. One of the interesting things about the company is that it’s only had two artistic directors, so the mission of the company has been very clear from day one. Our mission is really to present rarely performed operatic masterpieces in concert with singers who are hopefully new to D.C. or haven’t sung here very much. Partly the reason that these pieces are so rare is because they’re difficult to do full presentations of. Because they’re rare we can do them in concert and present them to a very specific audience in a way that would be more difficult to do if you were to fully stage them.

We also love the idea of opera in concert because it’s a very different experience for the audience. We sort of strip away the staging, but we’re still left with something that is very dynamic and dramatic because you have the orchestra up there on stage. People who have never been to concert opera are often a little surprised about how dramatic it really is, because you’re constantly seeing 90 to 100 people up there. Usually in opera the conductor is hidden down in the pit with the orchestra, and I’ve been told I’m rather expressive and sometimes fun to watch.

Is the audience seeing the singers standing in front of microphones? Are they seeing people interacting with each other? Are they seeing movement or does it depend?

Mostly it’s a reasonably straight concert presentation. I mean the singers interact with each other but there’s no set staging. There are a few discreet microphones around because we’re recording for delayed broadcast on WETA that usually airs six months or a year later. It doesn’t always happen but on this occasion it is. There’s not a lot of movement on the stage but there’s a lot of sort of dynamic interaction between the singers and with me and the orchestra.

Are you the head of a roughly analogous organization in Australia? Or am I thinking of a group that is fully staged but still does more rarely performed operas?

You’re thinking of Pinchgut Opera, and you’re quite right. Pinchgut Opera is an organization I also helped set up roughly 14 years ago, or slightly more actually. The two organizations are similar in certain respects. Pinchgut is fully staged even though it’s in a concert hall and the orchestra is not in the pit. It’s a fantastic acoustic where we perform and the audience has sort of the same delight in Sydney as in D.C., because they can see the orchestra and the conductor as well as the singers and the stage. At Pinchgut we tend to do two productions and we do four or five performances of each show. In D.C. we just do one performance of each show.

For Pinchgut, our emphasis is primarily on works before 1800 because I have a fantastic group of period instrument players there, the Orchestra of the Antipodes that I’ve recorded quite extensively with, as well as the chamber choir Cantillation, my professional chamber choir there that is really wonderful with that sort of music too.

I love the fact that I have two companies set up quite similarly in many respects in different hemispheres. It really gives me a tremendous amount of pleasure to be conducting rarely performed works on either side of the globe. It also informs my conducting of the standard repertoire so much when you conduct works that are often around the periphery of the standard repertoire but that other composers knew. I mean, Verdi knew Semiramide and he knew a lot of Rossini’s work, and so having conducted a lot of Rossini really sort of informs how I conduct early Verdi. It’s a wonderful, linear thing.

Can you give me an example of a piece of knowledge that you have from Verdi’s comprehensive knowledge of Rossini’s work that informs something you’ve conducted by Verdi?

Yes, for example, I’ve just conducted Nabucco by Verdi [at Pittsburgh Opera]. It was his third opera. He was quite a young man when he wrote it, he was still in his twenties. Rossini by that stage had stopped composing, and Italian opera was taken over by Bellini and Donizetti and Mercadante – the three of them were sort of the apex of bel canto. It’s interesting, if you listen to the overture of Nabucco, you can really be fooled into thinking you’re listening to a late Rossini overture. If you listen to [Rossini’s famous overture to] William Tell and then you listen to Nabucco, there are tremendous stylistic similarities. There are the really propelling rhythms and the crescendos and the way the brass introduce the climaxes, that sort of thing.

And the way it works with classical music, as it does with other forms of the arts, is that young composers are always learning from the older composers. There’s this tradition and growth with where the older composers are sharing the experience, sometimes through teaching and sometimes just by having their works performed, and each succeeding generation just sort of builds on that. A lot of my ideas for conducting early Verdi, you know, the buoyancy of tempo, the clarity of articulation, sort of the real forward thrust of the dramatic impetus comes from my study of bel canto and Rossini. And of course then before that, Mozart, because Rossini’s compositional gods were Mozart and Haydn.

I’ve been really fortunate to have the opportunity to conduct, you know, from Monteverdi’s Orfeo from 1607, all the way to Philip Glass [whose Appomattox is currently running at the Washington National Opera]. It’s a really fortunate position to be in, to have that sweep of 400 years of music.

Can you compare Australian and Washington audiences? Would you say that interest in opera is greater in one place than another?

Actually I really couldn’t say. I really haven’t thought about it in those terms. The terms that I have thought about are that we’ve been very lucky to attract in both in D.C. and Sydney really passionate audiences. If you come to a Washington Concert Opera performance, after the first couple of numbers you can hear the audience sort of cheering already. In Sydney we have a very sort of passionate and learned audience as well. They come along to both companies because it’s pieces that they can’t see anywhere else, and that really stimulates them.

Is Semiramide Rossini’s last opera, or longest opera – what am I looking for?

William Tell is after this, but Semiramide is the last opera that he wrote specifically for Italy before he moved to Paris full time. It’s a really interesting piece because, having said that Mozart and Haydn were his gods, this really comes across as a baroque opera [the period before Mozart and Haydn]. Also because of the subject matter, you know, kings and queens of antiquity. It’s got sort of quite massive structures to it, and tremendously virtuosic singing.

Why isn’t it staged more? Is it because of its size, or some other reason?

Yes. I mean, first, you have to have four really fantastic singers to be able to sing the four principal roles. They need a lot of stamina, they have to be capable of real feats of vocal virtuosity, and they have to be very skilled stage animals as well. And then there’s the whole pageantry of it. It’s quite a long piece. I think for Concert, I’ve cut about three-quarters of an hour of music.

Bless you.

Yeah …

I mean, you know how people are in Washington, you see what happens as soon as the final note of anything ends, people are running out, they have get back to the far suburbs or wherever.

No absolutely, and I recognize that.

I hate that, but you don’t see that in other countries.

Well no actually, you do see that in big cities where people don’t live in the center. I mean that happens in Sydney too.

I’m disappointed! I have these romantic notions of Australia.

Well but if you do it uncut, the first act of Semiramide, including the overture, takes actually two hours. You can perform all the music of La Boheme in that time! I usually think that 1½ hours is the maximum for any act to have an audience sitting there, so I’ve cut it so that the first act is just under 1½ hours, and the second act is 1:15 or something like that.

And also because there are some large chorus numbers and some large orchestral preludes which used to be used to change the set, and to bring in the chorus and set the stage, and in concert you don’t need that time. So it makes sense to tighten it up a little bit. I don’t think you lose anything except time, and you gain in dramatic thrust by tightening up like that.

https://youtu.be/WXP79dH4DHM

As someone who is sensitive to both musical history and performance history, let me ask you about bel canto [essentially early 19th century operas with long runs of notes on single syllables]. Why did it disappear from performances for what, about a hundred years, and then it came back? Because it’s hard?

The basic reason is that up until the 20th century, basically every style of music was superceded by a new style. In the 18th and 17th centuries in particular, it was hard to disseminate music because there were only a certain number of copies available. And everyone was always looking, as they are today, for the next big thing, for something new. Even Mozart’s operas sort of disappeared from the catalogue for a while. You know, I’m conducting Cosi fan tutte at the moment in Pittsburgh, and the person we have to thank for the resurgence of Cosi fan tutte was [late 19th and early 20th century composer] Richard Strauss, who sort of re-orchestrated it and suggested cuts.

It’s not really until the 20th century where you had opera companies that performed nightly in the big cities, because performers became so proficient – the singers and the instrumentalists – that they didn’t need quite as much rehearsal time to put on an opera, and once they rehearsed it, they could just keep bringing it back, because just the level of retaining what they had learned was higher, and people became used to performing different styles.

Previously if you were in Italy, all you would perform would be Italian bel canto opera. It was very rare for a German opera to be done in Italy until later. Once printed musical materials became more common, people started performing Wagner and French opera and Italian opera in the one house. And then there was like this taste for sort of rediscovering other composers’ works and composers from other times.

Now we’re in a very wonderful position where there are certain singers that like to specialize in bel canto or they like to specialize in baroque opera or they like to specialize in Wagner, and they all have slightly different techniques in order to be able to achieve these styles. And some singers can adapt their technique to sing quite a few styles, which is good for them as well.

Where are the current generation of bel canto singers coming from?

It’s a complex answer but I’ll give an example. A lot of Australia’s best singers originally came from what we sort of call working-class backgrounds, these wonderful, healthy physiques. Some of these guys worked in construction, or as farmers or things like that. You know, the big barrel-chested men who had these really stentorian voices. Nowadays with the rise of a middle class, and with a generation of people growing up working on computers and things like that who were not used to doing manual labor, there are these singers who are a little smaller, a little slighter, with more sort of more flexible, lighter voices.

On the Australian stages you used to see these very stocky, very strong-looking singers that had sort of big muscular voices, and now they’re slimmer and more lithe, with slightly lighter voices. It’s great because nowadays you get people who come to singing from church, or who just did it because their dads did it and their mums did it, and they can either be from working class or middle class or whatever. And everyone has a way of getting into singing and getting into a conservatory or taking lessons. You have this one fantastic range of singers with totally different physiques and the ability to have different techniques and different sounds. So we’re really fortunate now to have such an array of talent.

If I’m in the audience and I know something about The Barber of Seville or La Cenerentola (also known as “Cinderella,” which the Washington National Opera performed earlier this year) and I think of these Rossini operas as comical, so is that at all like Semiramide, or is it totally different?

Well, Rossini’s vocal language in Semiramide is very similar to The Barber of Seville, but it’s a bit more sophisticated, I mean it’s eight years later than The Barber of Seville so you’ll hear more harmonic inventions, more interesting orchestration effects. And there are a few scenes in Semiramide that are really moving. There’s a great depth of emotion that runs through the piece. Sometimes you’ll hear this really stirring passage in the orchestra that you think, that’s right out of The Barber of Seville. There are some really lovely choruses in Semiramide. There’s not much of that in The Barber of Seville, I mean there are some great ensembles but not much chorus work.

You are doing the holiday presentation of The Barber of Seville this year at the Metropolitan Opera, right?

Yes.

Tell me how the Met designs the holiday season production especially for families.

There are a couple of ways. The first way is that it’s in English, so the language is immediately accessible to an American audience. The second way is that it’s slightly shortened as well. It makes it easier for younger audience members to keep track of what’s going on, and keep enjoying the performance. It’s a very perky, wonderful production. I think that helps too.

And who else is in it besides Isabel Leonard, who sang “Cinderella” here in Washington?

You have Isabel alternating with Ginger Costa-Jackson, who’s really wonderful as well. And you have David Portillo alternating with Taylor Stayton, who’s also singing in Semiramide, as Almaviva. You have Elliot Madore, a wonderful young baritone singing Figaro. And Valeriano Lanchas as Bartolo. It’s a really great cast.

Let me ask you a couple of things about singing opera in English. First of all, for The Barber of Seville, will there still be seat titles in English? [The Met projects titles on the back of seats rather than above the stage.]

I believe so, yes.

Does that put some stress on the cast to be more precise?

It depends on the singer. Most singers are not particularly concerned about that. It doesn’t matter to them if it’s in English or Italian, they just want to communicate and they want to be understood in whatever language they’re singing in. Sometimes if you’re an English-speaking singer singing in English, issues of memorization occur just because you know what the options are in your native language. Sometimes I’ve noticed that when I’m conducting Italian opera with Italians! Sometimes in the recitatives they will divert slightly from the libretto just essentially because they can say the same thing in a couple of different ways.

Well, you’re getting at why I asked. For example, the Met did The Merry Widow in English at the beginning of year. Nothing went wrong, but there were moments when the titles did not exactly match what the singers were singing, and the singers almost certainly were Americans or Brits who were just putting a different spin on it.

There’s an interesting conundrum sometimes when you’re super-titling in the same language as is being performed. Because when you supertitle, you don’t always put exactly what is being said every step of the way. Sometimes you would just have too many titles. I have no idea about The Merry Widow, but I can imagine that at some times there may have been two sentences that were said sung in quick succession and only one of them went up on the titles. You don’t notice that if the opera is being sung in Italian and you’re reading the titles in English.

Should parents bring their kids to The Barber of Seville?

Oh, I think so. If you have a child who is sort of interested in music and in theater, and can sit through something that’s an hour at a time, definitely. I think they’ll be really amused and engaged.

Even though as an adult, with comedies like The Marriage of Figaro and The Barber of Seville, sometimes I’m not always clear as to who’s pretending to be somebody else who’s actually pretending to be someone yet different!

That’s because we, with our adult minds, love to dissect everything. But the children just love to experience, and then they will draw their own conclusion about what’s going on.

Have you done the holiday presentation for families before at the Met?

I have not, but I’m really looking forward to it. One of the things I love doing here in Pittsburgh is sometimes we do matinee performance for students, and you’ve got about 2,000 kids in the audience, most of them who haven’t seen an opera before. The Daughter of the Regiment was the last one we did, and they loved it, it was a really funny production with Lisette Oropesa who is amazing, and she’s very fit. She ran the Pittsburgh Marathon the day after we opened!

Isn’t Isabel Leonard another opera singer who has a reputation for physical fitness?

Very similar actually. So you know the kids, they loved what Lisette did, she gave a big performance as a tomboy, which you know everybody loved. I’m really looking forward to doing the holiday presentation, because you know, it’s more towards the families. There’s a slightly different energy that always occurs when you take that approach in the auditorium. It’s just delightful.

Let’s talk about you, Antony. If I have this straight, you are a trained instrumentalist, a professional singer, and a conductor. Is that correct?

Well at the moment, I have not sung professionally or performed as an instrumentalist for a few years. But I certainly trained as a singer and I have sung professionally as a singer.

But I think of music as something you have to focus on with a specific skill. How did you train as both a cellist and a singer, a tenor, and then a conductor?

It all started when my mother took me to piano lessons when I was about 8 years old. I kicked and screamed – I mean metaphorically speaking. Then I had the most fantastic, wonderfully nurturing piano teacher, a Hungarian woman called Elizabeth Kozma. She had formerly been the deputy director of the Franz Liszt Academy in Budapest. When the Russians came into Hungary in 1956, she escaped like my mother did – my mother is Hungarian. They didn’t know each other in Hungary, and they didn’t know each other in Australia for a while, but they both independently came out to Australia.

She realized very early on training me as a pianist that I wasn’t going to be a professional pianist or someone who had a tremendous facility on the instrument, although I still play today and I play sometimes for coachings, and I learn scores and things like that – I sight-read very well but I can’t play a concerto. Part of her job as deputy director of the Academy was to figure out where people’s musical vocation truly lay. She thought I would have good hands to be a cellist. So I started taking cello at age 10 and I took to that. And I loved singing and I loved composing – I thought I was going to be a composer.

When I was about 12 I started going to symphony concerts, and I would take my full scores along and read along with them. Elizabeth and I would discuss my thoughts about those concerts. I used to get upset if I couldn’t hear in the performance what I saw on the page. She suggested I might like to try conducting one day, and I did. I started my own groups and took conducting lessons all the way through university, and that’s how the conducting took over. She was a great believer in me as a conductor. She knew by the way that I processed music and the way that I analyzed it and also the way that I liked to passionately perform it, and the way I understood the drama of music, that I would be a conductor. She passed away about 20 years ago, but I still think about her a lot because she formed the core of my musical values.

Tell me about your playing the cello, have you been a cellist in symphony orchestras, or a soloist?

No, when I was at university doing my bachelor of music, I used to lead the cello section in the university symphony orchestra, and just play chamber music. It was very clear to me that my true talents lay in singing, composition and conducting.

One of the things that I think makes me I think a useful opera conductor is that I studied singing for seven years, officially. And I still class myself as a student of singing. I love to sing and I love vocal pedagogy. I’m very fascinated by different vocal techniques and what you can achieve with them, and I love helping singers to achieve their very best. For Semiramide the singers I have are world-class so I support them by adjusting tempos, adjusting balance, I help them shape the architecture of the piece. When I’m working with younger singers I get more involved in coaching them on vocal technique as well as musical style.

Thank you, Antony. I look forward to Semiramide!

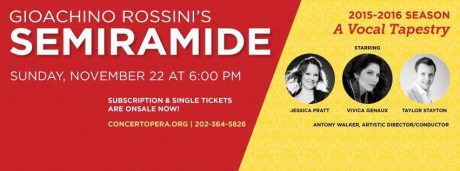

Semiramide conducted by Antony Walker will be performed by Washington Concert Opera on Sunday, November 22, 2015 at 6 p.m. at Lisner Auditorium – 730 21st Street NW, in Washington, DC. More information and schedules for Washington Concert Opera’s season and related activities are available on the company’s events calendar. In New York, The Barber of Seville opens at the Metropolitan Opera on December 16, 2015 and runs periodically through January 2, 2016. Complete information about Antony Walker’s recordings, repertoire and schedule is available here.