The production of Suzan-Lori Parks’ acclaimed three-part saga now having its regional premiere at Round House Theatre is some of the most amazing storytelling I’ve seen on stage. Amazing on account of the stories themselves, and equally amazing on account of how they are told.

In an essay titled “Possession,” Parks gives this provocative inkling about what she’s up to:

[T]heater, for me, is the perfect place to “make” history—that is, because so much of African-American history has been unrecorded, dismembered, washed out, one of my tasks as playwright is to–through literature and the special strange relationship between theater and real life—locate the ancestral burial ground, dig for bones, find bones, hear the bones sing, write it down.

And that’s exactly what Parks does in Father Comes Home… The language alone—an idiocyncratic mix of imagery and idiom, delivered by an extraordinary acting ensemble—is unmistakably alive, a unique aural experience of passion, poetry, and proclaiming. Not to mention the pleasures of the play’s political profundity, its touching truisms, its comedy, its twists and turns.

The play begins in 1862 on a plantation, where four “less than desirable slaves” as the playscript calls them (Jefferson A. Russell, Jon Hudson Odom, Stori Ayers, and Ian Anthony Coleman) are trying to guess whether Hero (Jaben Early), also a slave, will leave with their owner, who’s headed off to join the Confederate Army and wants his loyal lackey along. Hero’s decision is fraught with complications, and the way Parks plays them out and strings everyone along is utterly engrossing. There are complex relationships to reveal between Hero and Homer (Kenyatta Rogers) and between Hero and Penny (Valeka J. Holt). By the time Hero declares he’s going, the stakes of the story have scaled to the epic heights of Greek tragedy: an enslaved “Colored man” who’s serving his “Boss-Master-Boss” who’s serving in battle on the side that’s defending slavery.

“All we’ve got is the trust between us,” counsels The Oldest Old Man (Craig Wallace). Yet as the drama about Hero’s choice unfolds, Parks lets us see clearly how it’s a Hobson’s choice—and how easily what tethers these characters together could be severed in this system where they have no say.

One of the many powerful achievements of the play is Parks’ portrayal of the way “race” gets projected and parlayed in the systematic privileging of “white.” In her essay “An Equation for Black People OnStage,” Parks poses these questions:

Can a White person be present onstage and not be an oppressor? Can a Black person be onstage and be other than oppressed? For the Black writer, are there Dramas other than race dramas? Does Black life consist of issues other than race issues?

Parks herself takes up the challenge in those questions—in three plays that take place in the Civil War South!—with unique and astonishing ingenuity and artistry.

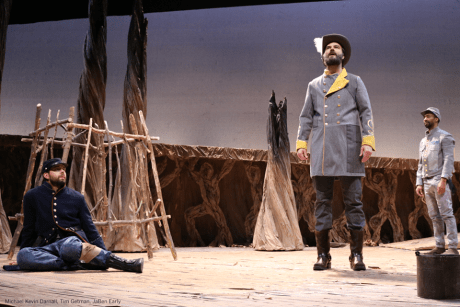

Part 2 is set in a wooded area where a Confederate Colonel (Tim Getman) and his captive, a Union Captain (Michael Kevin Darnall), are lost somewhere midway between their respective approaching armies. Hero enters carrying the wood and water his master directed him to fetch, and what follows is an extraordinary sequence of scenes on the themes of race, freedom, and human worth that are no less insightful for being hilariously entertaining. The poppycock Colonel, for instance, has a show-stopping monologue that begins, “I am grateful every day that God made me white” and ends “For no matter how far I fall, and no matter how thoroughly I fail, I will always be white.” The night I saw the show, I heard gasps of recognition that dared not breathe, the uneasy sounds of squirming, explosive guffaws. Was it meant to be funny? In her essay titled “Elements of Style,” Parks tips us off to her revolutionary use of humor:

Laughter is very powerful—it’s not a way of escaping anything but a way of arriving on the scene. Think about laughter and what happens to your body—it’s almost the same thing as throwing up.

The overarching and cumulative effect of this masterwork, masterfully directed by Timothy Douglass, is an experience of brazenly original storytelling and blazingly theatrical style that will keep you riveted—and your mind in a state of being blown all during and long after.

Running Time: 3 hours, with two 10-minute intermissions.

Father Comes Home from the War plays through October 4, 2015 at Round House Theatre – 4545 East-West Highway, in Bethesda, MD. For tickets, call the box office at (240) 644-1100, or purchase them online.

LINK:

David Siegel reviews Father Comes Home From the Wars (Parts 1, 2 & 3) on DCMetroTheaterArts.