Ntozake Shange’s music-drama, for colored girls who have considered suicide/when the rainbow is enuf [“for colored girls”] (1976), comprises a seminal work of poetry, music, and improvisational dance. In a series of twenty poems, Shange creatively self-describes her work as a “choreopoem” of pain, suffering, abuse, strength and resilience, and imbues it with a joy which is ultimately cathartic for each of seven Afro-American women. What does it mean to be a woman of color in a racist and sexist society?

In for colored girls the theme is physical and psychological abuse ranging from girlhood innocence through adolescence to self-discovery and adulthood, and the subjects are racism, sexism, rape, powerlessness and male domination. Do not expect this work to be a conventional theatre production with a traditional theme or plot neatly tied up in a bow. Rather, Shange eliminates characters and plot, presenting the women individually and collectively in one unified voice of pain and redemption within a mixture of genres—poems, narratives, dialogues, and dance.

Staged in an tenement apartment building with chairs and a bench outside the brick building, the women rotate front and center from their apartments reciting poetry and at times singing, to music and dance. Sometimes the dance is joyous, other times it is harsh rendering the women vulnerable. If fortunate to see this play at another time, expect to hear raucous, gritty, street language that assails your ear and may even cause you to gasp or shrink back in your seat. These women are in pain and the niceties of a Sunday school monologue or a lunch time chat at work do not apply.

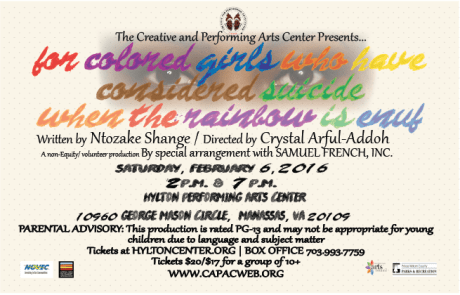

In the Creative and Performing Arts Center (“CAPAC”) production of for colored girls, presented in two performances on Saturday, February 6, 2016, each woman through a series of poetic monologues and dialogues recited a poem, while several danced in support and collectively the women provided a chorus effect for each other’s pain-evoking exhortations. Adorned in the colors of the rainbow, the seven Afro-American women clothing signify life and hope in varying degrees, while the brown color represents birth and a connection to mother earth.

Skillfully directed by Crystal Arful-Addoh and Creative Director, Tyrell Lashley, a CAPAC favorite, for colored girls began with a dark stage. As the lights went up seven women are seated in six variously rainbow colored chairs and one park bench with a sign reading ‘Will Work for Food.’ Against the powerful words of civil rights activist Nina Simone’s 1966 revolutionary song, “Four Women” whose lyrics overlay the seven colors, we are presented with a dominant theme describing how the women believe their sex and skin color is perceived and disrespected in a country run by white people and in a world run by men. All the women share a feminist point of view. In Shange’s black feminist ideology, her lens fixates only on the negative effects of black male abuse of black women. Shange utilizes Simone’s poem to show that black women, whether their skin is black, yellow, tan, or brown they are “Between two worlds / [wondering where] I do belong . . .” and questioning if they are “Strong enough to take the pain / inflicted again and again . . .”

Under Crystal Arful-Addoh’s capable direction, we empathize with the women and are drawn into an intimate identification and understanding of their suffering. Their struggles are real and raw and more than once I resisted a strong compulsion to leave my seat to gather around to comfort them as if we were gathered in a circle at church.

Performed by Renea Brown, the Lady in Brown, the choreopoem opens by describing the purpose of the piece, to “sing a black girl’s song/ bring her out of herself.” Opening with the first poem “dark phases,” the Lady in Brown speaks of the pain and misunderstandings that mark the youth of a black girl. It’s 1955 and she is forced to experience integrated schools, wondering why white children can’t take three buses to get to her school. Ms. Brown’s performance was poignant for me, evoking memories of my own early childhood in Pittsburgh’s segregated schools.

The Lady in Yellow, performed by Kayann Lyle tells the tale of virginity lost in the back seat on graduation night after a full night of dancing and partying. Her feigned bravado claiming that it was great did little to cover her shame. A lover of everything dance, she laments “my dance was not enough but it was all I had.” Ms. Lyle’s stage performance was exceptionally skillful and while virginity is an important subject, it also evoked a considerable amount of laughter and audience recognition.

Renita Cole, acting as the Lady in Blue, recites the poem “now I love somebody more than” which is initially a poem of gratitude that attests to the immense joy that music and dance can bring to the human spirit. Ms. Cole performance is sophisticated as she moves about the stage; something about the soft blue color of her blouse adds an air of royalty to her presentation.

Lisa D. Nokes as the Lady in Red, performed a major character role in the piece. Red is a seductive color, vibrant, brash, vivacious, energetic, exciting, effervescent, and spirited. I could go on and on. Ms. Nokes Olympic performance ‘struck the bell’ with aplomb as she recites “no assistance,” a poem of rebellion and disgust, forcefully berating a lover who failed to assist her in maintaining their relationship. Now weary; she returns her lover’s plant she had been tending and ends the relationship taking her power with her. Along with others, I clapped gleefully as the Lady in Red regained her emotional strength. Ms. Nokes recites another intense poem, “latent rapists,” by acknowledging the repulsive yet true fact that a rapist is often a personal acquaintance of the victim. In such cases, rape is an even harsher act of betrayal, being emotionally difficult to prosecute someone known by the victim.

Performed by Rhonda Oliver, the Lady in Orange portrays a poet and dancer who deftly delivers the poem “I’m a poet who,” . . . wants to write, sing, and dance but decides she really cannot communicate with people anymore because it is too painful. However, in “no more love poems #1” the Lady in Orange finally admits that she had convinced herself that colored girls had no right to sorrow. Eventually she finds the emotional strength to acknowledge that she needs love despite the frequent failure of relationships between men and women. Ms. Oliver’s excellent performance is supported by the vibrancy of her orange clothing, evoking warmth and hope. As humans, we all want hope and love to prevail.

Terresita Edwards performing as the Lady in Green delivers a powerful, riveting and righteous performance to an enthusiastic audience where some stood up and cheered. As the Lady in Green is emphatically states and repeats over and over “somebody almost walked off with my stuff,” and we see a crouched woman dressed in green camouflaged fatigues who intends to get her “stuff back.” She surmises “I was dangling a ring of personal carelessness” as an acknowledgement of responsibility for contributing to her own personal situation. “Give me back my stuff!” My lips, my eyes, even the pimple on my leg. I cheered in appreciation that she was willing to fight anyone who would try to take her “stuff.” The origin of Ntzoke Shange’s adopted Zulu name adds even more meaning to this exposition because “Ntzoke” means “she comes with her own things” and “Shange” means “one who walks with lions.”

The Lady in Purple, played by Christina Wilson touched me deeply as pregnancy and abortion are synonymous with life and death, God’s exclusive domain, in my opinion. Against the backdrop of Roberta Flack’s 1973 “Killing Me Softly With His Song” and Ms. Wilson’s moving recitation of “no more love poem #3” we see her face alone the abortion of her fetus’ life, referencing the invasion of metal horses (speculum) inside her flesh as the physician removes life. She laments “nobody came, nobody knew.”

Mr. Lashley, Artistic Director, chose to update the music by including audience favorites such as Whitney Houston’s 2009 hit, “I Didn’t Know My Own Strength” lyrics resonated with the packed audience of mostly female supporters and local churchgoers, and I too, embraced the reality that I had made it through all the challenges of being Afro-American and female in America:

I didn’t know my own strength

And I crashed down and I tumbled, but I did not crumble

I got through all the pain

Oh, I didn’t know my own strength

In closing the choreopoem, the women gather around the Lady in Red seated comforting and congratulating one another and reciting “I found God in myself /and I loved her fiercely.”

In summary, although this particular piece focused on the lives of only seven Afro-American women, the issues they faced to redefine their own self worth as loved and respected black women essentially apply to “everywoman.” Shange’s lifelong driving mission remains giving voice to the voiceless by articulating the pains and triumphs of black women through poetry, song, and dance. While there is progress, that struggle yet continues.

Now into their sixteen year, the admirable effort of CAPAC to bring this important work to Prince William County is to be highly commended. They have shown the ability to remain true and constant to their craft and to give voice to subjects of interest to all.

for colored girls played on February 6, 2016 at Creative and Performing Arts Center performing at Hylton Performing Arts Center – 10960 George Mason Drive, in Manassas, VA. Watch for future performances by CAPAC by visiting their website, or by calling (703) 441-2479.

RATING: