At a point in Mosaic Theater’s Promised Land—a powerhouse of a play performed inside an intimate space that’s more like a concrete bunker than a black box—we see the searing image of people fenced out. Refugees, huddled masses depicted by a cast of seven, stand backlit upstage of a chain-link fence, their pleading arms upraised in shadow against a translucent screen. We hear no words yet the transcendent impact of that image rends the heart.

And who could have guessed that on the very day this play would open in the rehearsal room at Woolly Mammoth, Pope Francis would chide off the cuff ex cathedra:

A person who thinks only about building walls, wherever they may be, and not building bridges, is not Christian.

Turns out, as Promised Land makes plain, it’s not Jewish either.

The play by Shachar Pinkas and Shay Pitovsky tells multiple and interwoven stories of survivors of civil war in East Africa looking to Israel for asylum, i.e., some semblance of the national sanctuary that was made home to survivors of the Holocaust in Europe. It begins as the seven members, utilizing the theatrical form of devised documentary, address us directly and barrage us with statistics about the extent of the problem. It’s an onslaught of info that’s more than we can take in—”more than we can take in” being, of course, the point of view of those who want refugees kept out.

The play does not hold back in portraying the prejudice in the policies that have excruciating effects on so many seekers of safety. There is a chillingly smarmy speech delivered by the Mayor of Eilat (“My African friends, please go back to your homeland, we wish you well”) and a chillingly bigoted speech delivered by a contractor (“You might get Ebola from the sight of them, and if they sneeze on you, HIV is inevitable. What do I know about them? Why should they come from Africa?”)

Remarkably, though, the play in performance is suffused with youthful hope, which at moments comes through like an idealistic song sung against a din of despair. We are reminded of that disquieting context by Eric Shimelonis’s stunning sound design, whose vehemence jolts us, makes us jump, between each compelling scene. We cannot escape seeing that sinister world as represented in Andrew R. Cissna’s fierce set (that fence) and climactic lighting. Yet it is the performances of the young cast—especially when enacting refugees’ stories—that stand in starkly humane contrast and move us ever more deeply as the play proceeds.

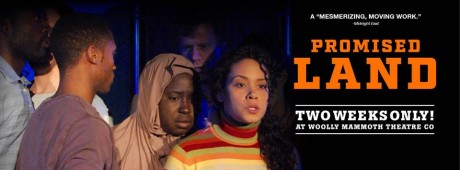

In multiple roles, under the vigorous direction of Michael Bloom, are Audrey Bertaux, Aaron Bliden, Felipe Cabezas, Gary-Kayi Fletcher, Awa Sal Secka, Brayden Simpson, and Kathryn Tkel. I witnessed each of them embody, in various ways and roles, the interpersonal case for an empathy-based ethos, which experienced as a whole overflowed the stage.

There’s a scene near the end where the actors each stand at a mic and say aloud actual telegrams sent by refugees in search of lost family members. The words of one of them seemed to give voice to the entire endeavor’s undercurrent of hope and longing: “I pray to God that there are no more barriers in the world.”

And later there’s a scene that’s an enactment of a vigil last May at which two rabbis, both women, spoke. Their words seemed the very heart of the play:

God repeated the commandment to protect the stranger at least thirty-six times because it’s a really hard thing to do. Now that we are in our own land, it is something that takes real faith in God, and embracing discomfort — in a way that keeping kosher or Shabbat does not.

But it is the real test of the Jewish soul. As Jews, we have suffered so much and so we have a great responsibility toward strangers. The refugees here need our protection, kindness and humanity. This is our religious and moral responsibility.

There is a palpable sense in which Promised Land—which was conceived and created in Tel Aviv at Israel’s national theater by an ensemble of young professionals—is fittingly played here by actors who are all close in age playing characters both older and younger than themselves.

As the third offering in its Voices of a Changing Middle East Festival, Mosaic Theater has brought us the invigorating voice and vision of a new generation of theater makers who see themselves as peacemakers and bridge builders.

Promised Land bears a title the brittle irony of which is little lost here in DC, and it must have been harsh to hear in Tel Aviv. But this is a nervy and unexpected work. In its inception it looks to the future, not the past. In its performance it could help move us there.

Running Time: 70 minutes, without an intermission.

Promised Land plays through February 28, 2016 at Mosaic Theater Company of Washington performing at Woolly Mammoth Theatre Company – 641 D Street, NW, in Washington, DC. For tickets, call the box office at (202) 393-3939, or purchase them online.

After the run at Woolly, the cast will take a concert version of the show to George Mason University March 1 and to American University March 2.

LINKS:

Review of ‘Promised Land’ at Mosaic Theater Company of DC by Robert Michael Oliver on DCMetroTheaterArts.