Cellist Rubin Kodheli joins the legendary performance artist Laurie Anderson on stage at The Terrace Theater for a presentation of her new multimedia work, the memory-haunting Language of the Future: Letters to Jack, through March 6.

Combining visually arresting photography and film with Kodheli’s cello and Anderson’s violin and electronics, Letters to Jack challenges its audience to a conversation: a mental conversation, between Anderson’s memories of Jack Kennedy and the 1960s and the presently political.

The results are profoundly provocative, as much for the conversation between music and word as for the interplay between the artifice of aesthetic media and the disturbing realities of the present.

The music is non-stop dialogue, half improvised and half set.

Kodheli’s cello speaks as conversationally as a cello might, sometimes entrancing our ears while at other times bopping them with stucco pops. Each sound, like each emotion, leaves us in eager anticipation.

Anderson keeps pace on electric violin, engaging the cello with insistence, as she turns to the microphone to begin her narrative.

For it’s Anderson’s seemingly life stories that give definition to Letters, lifting it wholesales out of its musical discourse and soaring it into memory.

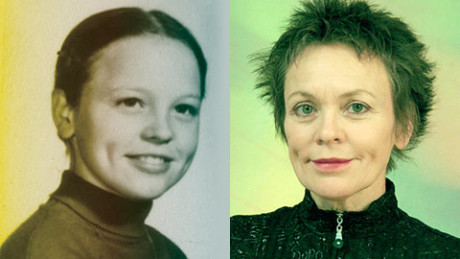

Anderson offers us personal narratives, beginning with her earliest encounter with Jack Kennedy from 1960.

Ms. Anderson, the story goes, was running for middle school president when she wrote a letter to Jack Kennedy, asking him for political advise. Jack, at the time, was running his own campaign against Richard Nixon.

Surprisingly, Kennedy responded with a list of politically cogent bullet points. One bullet in particular stood out: get to know your community, find out what they want, and then promise you’ll get it for them.

Yes, Letters to Jack has its funny parts, even if it’s sadly true.

Anderson won her election by the way (as did Kennedy later), no doubt, in part, by following Kennedy’s wise advise, which Kennedy himself demonstrated to perfection at story’s end when he sent a dozen red roses to the victorious Anderson.

Anderson delivers her stories in a simple, arresting style, sincere and seemingly without polish. Sometimes, in fact, her voice slips beneath the volume on the music and words are lost in the ether.

The most powerful story of the evening involved an Anderson childhood accident. While attempting a flip off the high dive, Anderson breaks her back on the side of the pool and is in traction for months. As with all of Anderson’s narratives, however, the focus is not so much on the events that happen, as they are on the way the events are remembered and recounted.

Such are the building blocks of culture; such are the building blocks of identity. For years, Anderson blocked out the most disturbing details of that terrifying event. As a result, the event was transformed.

Photography and film are used at key moments in Letters to Jack, and operate very much like bridges from one illustrative moment to the next. From snow falling on a city to hospital wards to Jack Kennedy, the visual is used as is memory, a fragmented yet figurative point from a larger narrative that a person can no longer grasp in total.

Brian H Scott developed the lighting design for the show, and it works wonderfully to help give focus to the discourse.

For in many ways Letters to Jack is dominated by the random, or possibly the analogical. Its connections are not obvious or apparent, as it mimics consciousness as it meanders from one point of light to the next.

As a result, one might easily write Letters off as diffuse.

The piece’s final narrative, however, returns us to that electioneering of 1960, when the grace and sophistication of Jack Kennedy left an endearing mark on a young girl.

Using a voice changer, Anderson offers a letter addressed to Donald Trump, and suddenly the past and the present, with its implications on the future, collide.

The voice changer makes Anderson sound more like a kidnapper demanding a ransom than the artist we came to know during the show’s first 60 minutes: her sincere, relatively unmodified diction has now become a modulated, and modified gruff distortion.

And suddenly, the 56 years between Kennedy and Trump are on full display.

The politics of “promise them everything” has not changed; but the manner in which those politics attract an audience is no longer recognizable.

The charm of the red rose has been replaced by the charm of the growler, courting not with sophisticated deception, but with quite obvious theatrics.

Such is the Language of the Future.

Such is Letter to Jack.

This provocative piece is for anyone interested in performance that pushes at the boundaries of media, exploring the intricacies of time and memory, while zeroing in on the politics of now.

Running Time: 75 minutes, without an intermission.

Language of the Future: Letters to Jack plays through March 6, 2016 at The Kennedy Center’s Terrace Theater – 2700 F Street, W, in Washington, DC. For tickets, call the box office at (202) 467-4600, or (800) 444-1324, or purchase them online.

RATING: