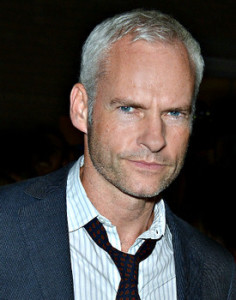

Martin McDonagh is one my favorite living English-language playwrights and I’m not really sure why. His plays are hilarious and horrific at the same time. And I experienced that counterintuitive combo to the hilt watching The Pillowman at Forum Theatre, about which my DCMetroTheaterArts colleague Michael Poandl raved:

For all the inspired performances and brilliant designs that characterize Forum’s stunning new production of McDonagh’s The Pillowman, the real star of the show is its director, Yury Urnov.

Figuring Urnov might help me figure out why I find McDonagh’s dark comedy so drop-dead funny, I asked him to sit down for a chat.

John: McDonagh’s humor is very offbeat; he makes the macabre hilarious in a way that might be unique to live theater.

Yury: I think it is. I worked on two of his plays as translator, interpreting them into Russian, The Beauty Queen of Leanane and The Lieutenant of Inishmore. The Irish and Russians have a lot in common—their attitude to life and death, to what’s funny and what’s not funny, some deep internal suspicion that all this existence is a joke, that somebody’s playing a game on us.

We have a lot of historical reasons to think so in both countries. It’s the world without a clear moral coordinate system, to say this is good, this is bad, because one thing is good today and bad tomorrow. In my country this coordinate system kept shifting so many times in the last hundred years. Things were going upside down completely. The idea of good and bad, what is moral what is immoral, what is a good person what is a bad person, what is existence, what is death, is there a god—all those questions are even more unanswered there than anywhere else.

How did the experience of growing up in Russia inform or influence choices you made as a director with this production of The Pillowman? The audience seated at tables, the interrogation-chamber set—was there stuff from your life that came into play?

There is such a long, almost genetic, memory of fear in my culture. My mom told me, “You see a policeman on the street, cross the street, walk by the opposite side.” You see a police car, somewhere deep inside you, closer to your testicles, there is a feeling of, I don’t want to meet this guy. If I need to go to the police department just to fill some kind of paper that has nothing to do with any kind of crime, you feel, Once I’m coming through this door I don’t know if I’m coming out. You know that if you get arrested, you are basically condemned, you’re going to jail. Court is still pretty much a joke. The percentage of people who get accused is incredibly high. Plus all the history of repressions and how this police judicial system is being used to do what the state wants to do at the moment.

This fear is deeply embedded in my subconscious. There is no way of avoiding that. You still perceive the interrogation room, the detective, as an absolute sadistic evil. You just do. You can then laugh at them, make fun of them, if that’s your way to fight this fear, but you’re afraid.

McDonagh takes another step, because when you start reading or seeing the play, it’s very clear who’s right. The police are judging and treating badly the writer. You know who is good, who is bad. But then McDonagh turns it upside down. It’s not that the police are becoming good folks, but they do have a freaking serious reason to do what they do to this guy. That’s another trick that McDonagh is playing so effectively: destroying the whole idea of who is good, who is bad.

McDonagh’s humor is probably surprising to American audiences discovering it for the first time; it’s so not like a television sit-com. It’s been called dark comedy, macabre humor, gallows humor—it’s got violence in it that’s been called Tarantino-style, Grand Guignol—yet it’s got gut-busting laughs. McDonagh’s humor seems to set up a unique relationship to the audience.

From the first day, we were very consciously trying to avoid actors pushing the audience to laugh. Because I don’t think it’s that kind of humor. We’re basically running away from the humor, honestly.

It’s a balance of tension and funny, because the moment you lose tension, it becomes cheap, just in a second. So technically speaking within the rehearsal room we were talking about, Yes, we need to permit the audience to laugh, but never to push it to laughter. It’s a thin, complicated line. It’s very easy to just prohibit laughter with how much tension you bring in, and it’s hard to leave the door two inches open to it.

The night I saw The Pillowman, it seemed as if at the beginning there was uncertainty in the audience about whether it was okay to laugh. By the second act, though, there were gales of laughter, because they finally figured out that it’s an amazing comedy.

I honestly like that. It’s a very horrifying play. It’s funny too, right? And I think the tension of these two games McDonagh’s playing simultaneously is the interesting part of that.

Laughter can do different things, and it can serve different functions. It seems the strongest, most interesting moments of comedy appear when the laughter is a reaction to doing something prohibited, to breaking through the wall of prohibition.

There are moments in the play when quote-unquote jokes happen when we’re talking about people being murdered, and McDonagh just juxtaposes these two pieces of information and emotion in one. And it’s your choice: Can you laugh at that?

I find McDonagh’s humor curiously cathartic. There’s something purging or cleansing about sitting through a McDonagh comedy—and never more so than in your production. And it’s kind of a mystery to me why his humor works that way.

I feel it’s about what’s prohibited and what’s not. I sometimes teach classes to people who never did theater. With people who’ve never acted before, I’ll give them a piece with violence or a piece with very open conflict. They’re first afraid to do that; they just refuse to do that. And then at some moment when they start doing that, when they start believing in the circumstances and they start feeling this rage or anger happening in them, their first reaction is laughter.

That’s so peculiar, and so human.

Right, because Mom and Dad told you that you can’t be aggressive in this cleaned-up society, you can’t show aggression. You can feel aggression; you can’t show it. So the moment I start doing that, I’m overcoming this barrier, knowing I’m in the safe circumstances of the theater. But I’m breaking through the wall of the prohibition. And I’m starting to protect myself from that by the laughter.

From the perspective of theater craft, how did you as a director approach McDonagh’s humor to make sure it played, to make sure the humor landed?

The biggest challenge is: How do you make a bold choice, a very bold choice, but keep it alive? I honestly think that Bradley Foster Smith, who is doing Ariel, the second investigator, is doing some work of amazing bravery. He has a scene where he has to go not just over the top but way, way, way over the top to make the scene work, and he has this amazing talent of keeping it humane while being up there. That’s what I mean about the challenge. The play demands, in my eyes, very bold, big choices, and staying alive in them. That’s hard, that’s tricky.

Like a lot of his work, McDonagh seems to want Pillowman to not be a message play; yet it tempts and teases us to find a message in it. It’s a roller coaster, whiplash story with issues in it—bad parenting, mental illness, the exploitation of children, writing and literature, state censorship—but is it “about” any of those issues, do you think?

I do think that the central theme and the heart of this play is about art and life, is about realities—quote-unquote fake reality and real reality. All the other topics that are there, obviously, are secondary to this main theme. I honestly find it a better way to talk about social issues when they are there but they are not formulated as the central message of the piece. When that happens—and it happens a lot in American theater—theater kind of slides to propaganda, to this Soviet kind of theater as a tool of social change. If we decide to do a play because we want to change people’s attitude, when that’s what our goal is, we’re limiting the tool of the theater.

Pillowman doesn’t have that objective. It’s more internal.

I do think it does it; it just doesn’t do it straight. After seeing the show, you can’t not ask yourself, Well, what’s more important, the freedom of the artist or the life of a kid? And in this play, it seems like McDonagh is provocatively more on the side of the work of art. He’s provoking that; he’s not announcing that; he’s not saying this out loud—I don’t think he believes it.

There is a political resonance in The Pillowman, which is set in a fictional police state with a Stasi-like interrogation going on. Do you think it plays differently in the U.S. and in Silver Spring in particular than it would in another country, in Europe for instance?

Well I do think theater always happens in a context. For me a Russian person—I’m sure for a Polish person, for a German person—when you see an investigator, there are so many things already happening in your brain and in your chemistry and in your blood that it could almost be considered an archetype. If I were directing Pillowman in European circumstances, the investigators would be different and the writer would be a different person. The context is forming our decisions.

And forming our perceptions of the play. Because we don’t live in a police state, apparently. And we don’t have those cellular memories of it as a culture.

I don’t think it’s just the archetype of the police in this context. It’s also the archetype of the writer, and who are you naming an artist in this context? In Russia the writer is and was historically probably the most mythologized. Russian heroes are writers—Pushkin, Dostoyevski, and Chekhov.

The U.S. doesn’t have hero writers like that.

They are the saints of the Soviet-slash-Russian pantheon, because they are considered moral orientaters, philosophers, the ones who explain to us how to live.

I’d like to read you a quote from McDonagh and ask you to respond however you like:

“I walk that line between comedy and cruelty, because I think one illuminates the other.”

I was growing up in the Tarantino generation. When I was like 14 or 15, I saw Pulp Fiction. And the first thing I thought even as a young man was: This guy is changing our perception of death. This guy can make death be funny and still be death at the same time. And I found that a cathartic experience. The permission to laugh at death, the permission to laugh at violence, made me feel more free, made me feel more open.

There is a town near Beslan where [in 2004] terrorists took over the school. A lot of kids were captured and a lot of them died and it was a national tragedy. Years later we did McDonagh’s Lieutenant of Inishmore there. Something happened in the audience when they realized they could laugh at the terrorist—that terrorists can be not only this horrifying, dark, untouchable figure, even within my own consciousness, but that this guy can be idiotically funny. And I remember this moment on opening night, this feeling of psychological relief—of: Yeah, they’re just crazy people. And in this darkest circumstance that felt so deeply optimistic.

Running Time: 2 hours and 30 minutes, with one 15-minute intermission.

The Pillowman plays through April 2, 2016, at Forum Theatre, performing at the Silver Spring Black Box Theatre – 8641 Colesville Road, in Silver Spring, MD. For tickets, call (301) 588-8270, or purchase them online.

LINK:

‘The Pillowman’ at Forum Theatre reviewed on DCMetroTheaterArts by Michael Poandl.

Note: Yury Urnov next directs Kiss by Chilean playwright Guillermo Calderón October 10 to November 6, 2016, at Woolly Mammoth Theatre Company.