On October 31, 1517, a young monk named Martin Luther nailed a list of 95 theses to a cathedral door in Wittenberg, Germany. It was a hammering heard round the world.

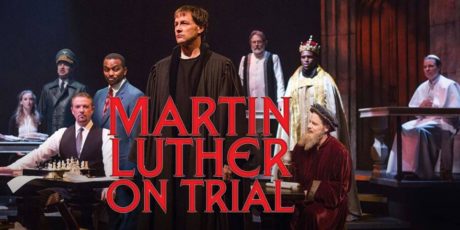

On the eve of the 500th anniversary of that confrontation with the Roman Catholic Church, the incendiary incident that launched the Protestant Reformation, a new play about Luther by Chris Cragin-Day and Max McLean, Martin Luther on Trial, will have its world premiere in Washington, DC, at the Lansburgh Theatre.

Luther was and remains a controversial figure. He was put on trial for his views by the Roman Catholic Church, he refused to recant them (“Here I stand, I can do no other”), and he was consequently excommunicated by the Pope in 1521.

The play Martin Luther on Trial, produced by the New York City-based Fellowship for Performing Arts, is framed as a fantasy set in the afterlife, when Martin Luther is tried again, this time with the Devil as prosecutor and Saint Peter as judge. The Devil sets out to prove that Luther committed the sin that Jesus called unpardonable. Luther’s defender is Katie, his wife. Witnesses taking the stand include Adolf Hitler, Sigmund Freud, Rabbi Josel, Saint Paul, Martin Luther King Jr., and Pope Francis.

I had questions about the play, and I knew I wanted to ask them of Chris Cragin-Day. She is an alumna of The Emerging Writers Group at The Public Theater as well as the O’Neill Theater Center. Her plays and musicals have been produced in New York City and around the country. And her take on Luther turned out to be eye-opening.

John: I had a look at your personal blog (which is beautifully written, by the way), and I read there you “grew up as a missionary kid then later left the bible belt to come to NYC,” and in relation to your daughter you referred to yourself as “a feminist parent.” You also teach playwriting at The King’s College, which is committed to “the truths of Christianity and a biblical worldview.” How does all of that—faith, family, feminism—come together for you as a playwright?

Chris: I believe that when God created man and woman, he meant for us to work together to understand ourselves and also Him. There’s a particular feminine understanding of both the human and the divine that is intentionally different from the masculine one. To understand God or ourselves fully, we need both. Unfortunately, through most of Western history, the feminine perspective has been devalued while the masculine understanding of God and humanity has been put forward as true. I don’t think it can be, not without woman. So in my writing, I try to fill in this gap a little. I try to tell stories of strong, wise women who have something to say about God and the human experience.

I greatly admired Max McLean’s solo play, C.S. Lewis Onstage: The Reluctant Convert, which he authored, and I know it was he who commissioned you to write a play about Martin Luther.

How did he happen to choose you, how was the project pitched to you, and how did your collaboration on the script work?

Max saw a production of my play Emily in New York City. It’s a play about Emily Dickinson, and I believe he liked my treatment of her as a historical character. So he approached me about writing a play about Martin Luther. I took some time to research, then originally I pitched a more realistic and straightforward telling of Luther’s story through the lens of his relationship with his wife, Katie. Max liked this take but really wanted to be able to offer a critical analysis of Luther’s historic impact. I’m a huge fan of Stephen Adly Guirgis, who wrote a play titled The Last Days of Judas Iscariot, which I love. So I pitched that as a kind of a model, and Max gave me the thumbs up on that approach instead. Our collaboration was really such that Max served as a kind of editor to pages I wrote on my own, which is unusual for the theater, but we took a chance and found that we work well together.

Have you been in rehearsals?

I’ve been in every rehearsal all along the process, and there have been small to large script changes at almost all of them. Bless the actors!

You wrote in your blog, “There is a character in the play that I feel a certain kinship with—Martin Luther’s wife, Katie Von Bora.” And the play begins with her. Would you say more about that kinship and Katie’s role in the play?

Katie was my way into this story. I could understand why she would love this man, why she would be excited by his teachings, inspired by his courage, and also disappointed in his failings. She was an incredibly strong, brave, intelligent woman in her own right. And she took a lot of criticism for it by Luther’s peers. But Luther loved Katie’s stubbornness and confidence, and that makes me love him even more. My father has done some pretty courageous and unconventional things in the name of his faith, so I feel I know the kind of man Luther may have been. Once I gave myself permission to put myself into Katie, the writing came easily.

You said about Martin Luther: “When I research this character, I feel like I am doing something illicit—peeking into his diary, unmasking the hero and seeing him for the rascal he really was.” And in another context you called Luther “a problematic man.” How do you mean “rascal” and “problematic”?

Luther was an amazing, beautiful, wise, passionate human being who lived up to his own advice to “sin boldly.” He wrote some of the most beautiful essays I’ve ever read, and also some of the meanest. There is a dark side to Luther that many Christians don’t want to look at. I felt like I needed to have the courage to look at it and call it what it was. But I also felt like I was betraying him by doing that. So I was, and continue to be, conflicted. And I’ve just decided that that’s okay.

I was raised Lutheran, so I’ve had more than a passing interest in Luther. In my youth I viewed him as a model of heroism, principle, and courage. As I grew older and learned about his misogyny and anti-Semitism, not so much. How does Martin Luther on Trial deal with those blots on Luther’s life?

Strangely enough, when I read Luther’s occasional sexist comments I see them as jokes. So much of his writing is Luther exercising his own wit. And I wonder if some of what he wrote was just ribbing. Probably not all of it. But the thing is, when you look at his marriage, you have to acknowledge that he was very progressive for his time. He invited Katie to participate in the table talks he had with the top theologians in Europe. She managed the money in the family. He tried to leave his estate to her when he died even though that was illegal. I credit a lot of this to Katie herself. But I credit Luther for seeing the value of her intelligence and gumption and allowing her to use it fully.

The anti-Semitic comments bother me more. They are so nasty, ugly, and, frankly, embarrassing to me as a Protestant. I tried really hard to find something at the end of his life where he took it all back, said he was wrong. But he didn’t. Devastating. It grieves me. I’ll never get over it.

There’s a surprising line in the play—it’s said about Martin Luther by the character of the Devil—“Only six people in all of history have had more biographies written about them….Shakespeare, Dante, Goethe, Cervantes, Lincoln, and Dickens.” I assume you didn’t make that up.

It comes from a bibliography of biographies. Fun fact.

There was also a 1961 play called Luther by the British playwright John Osborne. It was a biographical chronicle, and it famously made a point of Luther’s constipation—Luther was straining on the toilet as he wrote those 95 theses. How does your play differ from Osborne’s?

We include Luther’s physical ailments as factors at play in his decision making, but we don’t want to let him off that easy. “Pain isn’t an excuse to hurt people,” one of the characters says toward the end. Luther suffered from both physical wounds (kidney stones, ulcers) and emotional wounds (an abusive father). But he’s still responsible for his actions. That’s the stance we take. And of course, failure is required to understand grace, which is what Luther clung to in the end anyway.

You went to Germany on what you call a Martin Luther pilgrimage to sites where he lived, taught, nailed the theses, was tried. How did that journey affect your writing of the play?

I just felt I needed to inhabit his world with my imagination. The wonderful thing about Europe is that history is so tangible there. You can touch it, smell it, hear it. I needed to do that before I could tell this story.

What do you hope audiences will get from their experience of seeing Martin Luther on Trial?

We want audiences to find themselves confronted with both the beauty and ugliness of Luther—to feel permission to love his heroism, courage, and passion for the truth, and also to feel permission to condemn his anger, bitterness, and (at times) cruelty.

Martin Luther on Trial plays May 12 through 22, 2016 at Fellowship for Performing Arts performing at Shakespeare Theatre Company’s Lansburgh Theatre – 450 7th Street, NW, in Washington, DC. For tickets, call the Shakespeare Theatre Company Box Office at (202) 547-1122, or purchase them online.