A long-ago love story inspired this richly textured play with 1920s music. When Playwright Steven A. Butler Jr. was growing up, he heard family stories about how his great-great grandparents, Ruby Dyson and Ollie Tyson, fell in love in 1927. They met and settled in the small town of La Plata, Maryland, and began a family that now extends for generations.

Ollie and Ruby’s gifted great-great grandson has now imagined the world their love began in as a traveling circus. It’s an inspired idea. The owner of this circus is a white man. The townspeople the circus plays for are white. And all the circus performers and roustabouts are “Colored” (the word used throughout the script in its period sense). The result is not only a hugely satisfying saga bursting with heart, humor, and song. It is also a profound narrative metaphor for the black family’s struggle to survive under conditions of prejudice and exploitation not far removed from slavery.

The set is the interior of a worn and tattered tent. Swaths of burlap drape up to a pinnacle where there’d be a tent pole and descend to surround the playing area, which is strewn with straw. At one end is a high stage all set for live performance. Platforms suggesting straw bales make a secondary stage. Clusters of old-time wood tables and wicker chairs evoke transient living quarters, and an old Victrola lends the place a touch of home away from home. It all promises “backstage drama!” and “showtime!” and the show, engagingly shaped by Director Courtney Baker-Oliver, delivers both in equal measure.

Wonderful music arises during the dramatic action—ballads, torch songs, novelty show tunes, and more. (The delightful original songs are by Baker-Oliver, Butler, and Christopher John Burnett; the deft musical direction is by Burnett and Willie Ferguson.) In Act One, while we are being introduced to each of the thirteen characters, there’s more talk than singing; in Act Two, after we’ve met them, we are treated to more musical performances. The structure of the show draws us closer not only to the characters’ stories but to the meanings in the music.

And what moving stories they are. There are upwards of a dozen and they interweave and intersect throughout in ways that are by turns surprising, touching, shocking, and stirring, like a sprawling mini-epic.

Restoration Stage, which has produced this and other works by Butler (including his acclaimed Chocolate Covered Ants last season), has as its tagline “Restoring the black family—one story at a time,” which perfectly describes Butler’s present accomplishment. The first African American man to be named to the Arena Stage Playwrights’ program, Butler has just given American theater a masterpiece of empathy, entertainment, and uplift.

As the play began, it took me a few moments to catch on to Butler’s genius in crafting and combining all his character-driven narratives. They just seemed to come fast on the heels of one another, each a fragment unto itself. But then I realized what a powerful tapestry of troubles and longings Butler was weaving, what a sensitively embellished depiction of a community connected in struggle, what an act of love it had been for him to tell of the origin of his forebears’ devotion within a larger family context. And by the end I was in awe.

Because so much of the pleasure in watching this work is discovering its manifold subplots, I’d be remiss if I gave them away. But I can preview a few of the couples stories, because as is typical in classic comedies, there’s a pleasing payoff at the end of joyful pairings off.

Butler casts his great-great-grandfather Ollie as ringmaster of the circus, which he once owned but sold to a white man, Benjamin Boswell. In Pat Martin’s performance Boswell now lords it over the troupe like P.T. Barnum channeling Simon Legree as a pimp. Miles Folley brings to the role of Ollie such a physical agility and adorably earnest charm that it’s no wonder he catches the eye of Butler’s great-great grandmother Ruby, and no wonder this vivacious chanteuse catches his. The character of Ruby emerged for me as the play’s most knockout role, and Ayanna Hardy’s performance in it is heartbreaking. By the time she belts the first solo in the show, “Darkies Never Dream,” she holds the audience in her arms.

Juxtaposed with the young lovers, Butler introduces an older married couple, nicknamed Pumpkin and Pickles, who have been on the road like seasoned vaudevillians. They do a musical-comedy routine in the second act with the cringeworthy title “Oh, You Coon,” and Corisa Myers as Pumpkin and Charles W. Harris Jr. as Pickles bring down the house. They also have an indelibly moving scene together during which they tell why they fell in love with each other, and who they are to each other.

There’s a late-arriving romance near the end involving two of the white characters, Boswell’s son Colby and Leonora, who comes from a well-to-do family in town. Colby’s complex connection to the other story lines is fascinating, and Robert Hamilton does a good job conveying it. Despite being upbraided by his abusive dad, he has no inclination to take it out on others, i.e. the showpeople whom he manages; instead he identifies with them as family. When we first meet Leonore she seems the embodiment of clueless white snobbery, and Suzanne Edgar plays it to the hilt. She delivers a terrific ballad in Act One, “By the Light of the Silvery Moon,” and in a twist goes useful-liberal at the end.

Besides the Ensemble’s opener, “Circus Theme,” there are three other musical numbers in the first act, each owned magnificently by one of the foregoing female singer-actors. The third is Pumpkin’s funny-sad “I’m a Little Blackbird Looking for a Bluebird.” And it’s Pumpkin who brings us back after intermission with a rousing rendition of “Good Trouble” full of risque insinuation.

The innuendos roll on with “I Ain’t Gonna Give You My Jellyroll,” sung sweetly by Abiola Yetunde as Birdie, a shy roustabout who has taken a liking to an older roustabout named William (a fine Mandrill Solomon).

Even in a play full of fascinating characters, the originality of Freda stands out. She sings a song called “Mr. America” wearing faux Native American garb. Actually she’s Mexican and longs to return to California but keeps up this phoney gig like a trouper believing it’ll help her get there one day. Sara Hernandez’s performance in this role is among the most poignant in the play.

Everyone in the circus ran away to join it at some point, and some of their backstories are wrenching. Ruby’s and Ollie’s certainly are. There’s a scene between them about their pasts that completely choked me up. So did Zola’s. Madam Zola, as she styles herself, is an exotic, a fortune teller, one of those characters so out of left field they might belong in another play—until their heart-stopping story is disclosed. Zola has another of the female solos, “You Can’t Tell the Difference After Dark” (more innuendo), and Brittany Timmons sells it for all she’s worth.

There’s a tragically sad story line about a character nicknamed Tumbler (well played by Obinna Nawachuk), a simpleton who performs as a primate, dressed like a cartoon monkey. He longs to see his grandmother again, and just as Freda endures the humiliation of acting like an Indian, he naively believes this sideshow job will reunite them.

There’s also a fourth white character, Daphne, who is Lenora’s high-society friend and like her a snob. Unlike Lenora, however, Daphne is visibly uncomfortable around the Colored characters, and Jenna Murphy’s performance keeps that aversion very credible.

There are few moments in Butler’s play that are not in some sense about race. One of the qualities of his writing that caught my attention early on is the fact that the four white characters in it are always white; they never become unraced or raceless as they would in a play—written by a white author, say—where nine characters are white and four are black. In such a case the black characters typically stay portrayed and perceived as black while the white characters are portrayed and perceived as “race-neutral generic human.” That never happens in The Very Last Days of the First Colored Circus—to the deep credit of the entire production.

Over and above the outstanding music, performances, and production values in Stephen A. Butler Jr.’s The Very Last Days of the First Colored Circus, there is its eloquent testimony to the resilience without which the black family in America could not have survived the African diaspora. To watch that dramatized in the fictional context of a traveling circus is to see the obstacles in an imaginative new way but also to appreciate again the persistence and virtuosity that, within the remembered bonds of African kinship, overcame, went forth, and multiplied.

R.I.P., Ruby Dyson and Ollie Tyson. A great-great grandson of yours just did you proud.

Running Time: Three hours 15 minutes, including one 15-minute intermission.

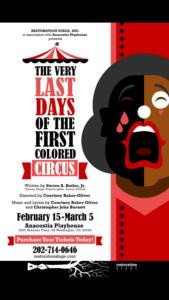

The Very Last Days of the First Colored Circus plays through March 5, 2017, at Restoration Stage performing at the Anacostia Playhouse– 2020 Shannon Place SE, in Washington, DC. Tickets are for sale online.