Avant Bard’s The Gospel of Colonus is a gorgeous, rapturous musical. Taking a phrase from the Bible, specifically Psalm 100, I found The Gospel of Colonus a “joyful noise” to witness and highly praise. I easily took the Avant Bard commanding, emotionally charged Colonus into my heart and soul.

Originally performed more than 30 years ago with huge casts, Colonus’s “bracing mix” of African-American and ancient Greek culture has not been diminished by the Avant Bard intimate staging nor by time. As one involved in the business side of two DC-area professional theaters over the decades and in a position to always ask whether artistic creativity and vision will sell tickets, let me add that Avant Bard Artistic and Executive Director Tom Prewitt and his folk are to be well-praised for taking on a production that would be expected to challenge audiences. That takes balls.

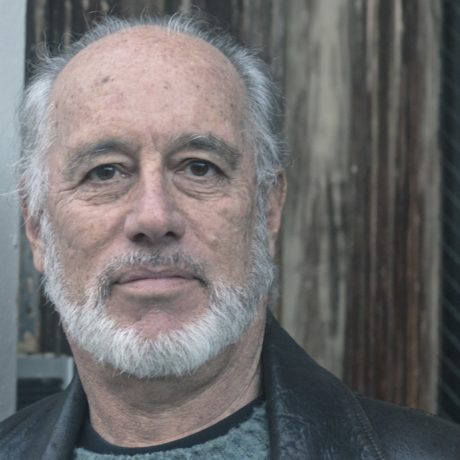

When I learned that Bob Telson, composer of The Gospel at Colonus, planned to take in the Avant Bard production, I jumped at the opportunity to interview him.

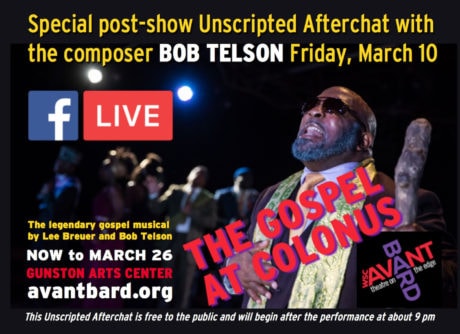

I have also learned that Telson will take part in two Unscripted Afterchats (Avant Bard’s facilitated post-show discussions)—the first after the evening performance Friday, March 10th (starting a little after 9 pm), and second after the matinee performance on Saturday, March 11th (starting a little after 3:30 pm). Unscripted Afterchats are free to the public. One need not have been at the performance to attend.

And as an aside, this unedited interview with Telson was delightful, and filled with great openness and candor. Rare indeed.

David: As I understand you went from working with Philip Glass to working with the Five Blind Boys of Alabama. What was the motivation for that?

Bob: There was certainly no conscious motivation for that particular transformation. I have always had a fascination with understanding different musics by immersing myself in their cultures and learning the vocabulary of their languages by being a working musician within their genre. The Philip Glass Ensemble from 1972–74 was my first real gig after studying music at Harvard. At that time Glass’ music was mostly unknown outside of New York, and it was very exciting to bring a truly new listening experience to audiences—some hated it and walked out (“Phil Glass’ Sonic Torture” was the headline in the Cleveland paper when we played there)—but those who stayed to listen were transformed by the experience.

Soon after that I turned my focus to writing and performing R&B. The band I formed had a great soul singer named Sam Butler, freshly arrived in New York from a Southern Baptist upbringing. His father had played with the Blind Boys, and Sam himself started getting me work playing piano and organ on gospel recordings he was hired to play on. By the time our band broke up, crushed by disco in 1979, Sam was touring with the Blind Boys and got me the gig as well to play Hammond organ with them. The experience was revelatory—on the road, playing Black churches, being part of the history of gospel music. I also started attending Black churches, drawn at first by the power of the music, but eventually gravitating towards the experience that would serve me well when Lee Breuer and I put together The Gospel at Colonus a few years later.

What was the impetus for you and Lee Breuer to relocate the tale of Oedipus to a Black church and transform it into a musical?

That amazing idea was purely Lee’s—I think he saw that Sophocles’ Oedipus at Colonus was written somewhat in the form of a teaching/sermon on old age, acceptance, and a happy death of redemption after a lifetime of suffering for sins committed in innocence. And why not imagine an imaginative preacher reading from The Book of Oedipus instead of the Book of John? Lee’s genius was seeing that he could make Greek tragedy relevant and at the same time open the doors to the Black church experience to audiences that might otherwise not have that opportunity. My role in working with Lee was often to be a catalyst, turning him on to different worlds of music that he would be inspired by to make a fresh amalgam with. After seeing me perform with the Blind Boys in a Harlem church, he hatched the idea of having them collectively portray the blind Oedipus.

How did, if it did, working with the Five Blind Boys of Alabama influence and inform the music you composed for The Gospel at Colonus?

Wherever we performed, there was always an undercard of both local and well-known gospel quartets performing before us. I heard a great deal of wonderful music, learned a lot, and met many great artists, such as The Soul Stirrers, who we recruited to have a major role in Colonus. Likewise the theatricality of the old-time quartets like the Blind Boys gave us a lot of insight into how we could adapt it to the musical stage.

What was the greatest challenge in composing the music and additional lyrics?

The part I loved the most was finding the most evocative musical expression for what the Sophocles narrative required. Lee would show me a section of the text, such as the section where Oedipus is turned back by the locals of Colonus. The bluesier side of gospel and older R&B worked well for “Stop Do Not Go On.” Likewise the Delta blues guitar of the Polyneices bad-boy scene was appropriate for that expression. The foot-stomping, hand-clapping Pentecostal songs “Never Drive You Away” and “Lift Him Up” serve the celebratory spirit well. Occurring near the end of each act, they also give the audience a chance a stand up and feel the spirit. The more classical songs “Numberless” and “Love Unconquerable” work best for the philosophical depth of their subjects. The last song, “Now Let the Weeping Cease” is my gospel sing-along version of “Hey Jude,” where the lyrics are repeated and everyone goes home happy.

As for the lyrics, I loved working with Lee to find the thin line that would 1) make the transformation of dialog in the Sophocles into lyrics that could be believably sung by a gospel singer, and 2) maintain the beauty and meaning of the written poetry. Putting Sophocles into the vernacular without downgrading it.

Why do you think that the music you composed for The Gospel of Colonus reaches into the hearts and souls of so many, no matter their cultural background or religious beliefs?

It’s certainly a combination of things: it’s a great story, and the telling of it is enhanced not only by the music I wrote but by the wonderful performers who personalize it. (I think you could say the same thing about the movie Bagdad Cafe and the song “Calling You” that I wrote for it.) I might also say that as a teenager I was a pipe organist playing Bach, and though the music and the ambiance is different, the desire to reach hearts and souls is similar. I’ve always strived in my music to have that effect. As for cultural backgrounds and religious beliefs, being a Jewish nonbeliever myself presented no obstacles to me personally in finding a powerful spiritual message in the Black church experience, and it was my goal to open the doors to that same revelation in putting together Colonus with Lee.

Why do you think the myth of Oedipus still “calls” to modern audiences as they take in The Gospel of Colonus?

Just as a good preacher will find a contemporary relevant message for his congregation by drawing from the Scriptures, the story of Oedipus has a universality in the suffering he undergoes for sins committed in innocence, and the redemption he finds after all his long years as a blind castoff beggar makes for a “happy death” that resonates with a contemporary audience and brings a joyful, participatory end to the evening.

For you, what is or has been the most lasting memory of your association with developing The Gospel of Colonus?

Rather than try to forge a lucrative career writing jingles, I spent my 20s and 30s following my ears in whatever direction seemed most interesting. From Phil Glass to Tito Puente and Machito, to the Blind Boys, to Trinidadian Steel bands, I wandered fascinated but clueless as to how I could use all this information to write my own work. When Colonus opened in 1983 to great critical acclaim, it somehow justified my musical vagabond heart.

Other than that, the joy and thrill of having our work accepted by the great gospel performers we have worked with, who early on hugged us and tearfully let us know that they could use our creation as an extension of their own ministry. And further, the way that these artists made my music feel at home in a Black church setting. Lastly, the lifelong friendships I’ve formed with many of the performers.

If you could invite Millennial audiences or those who do not go to theater often to see The Gospel of Colonus, what would you say to them?

I would say that the beauty of our show is that it can be appreciated on so many different levels—it’s the opposite of a one-dimensional experience. At a basic level, the music, as performed by the singers and musicians, is very accessible and at the same time original and surprising—you can clap your hands, but you can also have a deeply reflective experience. Likewise, the doors to the Black church experience are open in a nonliturgical way. And the same Sophocles that I had difficulty keeping my eyes open reading in college comes to vivid life with the poetry and meaning of ancient Greek tragedy intact.

Running Time: 90 minutes, with no intermission.

The Gospel at Colonus plays through March 26, 2017, at Avant Bard performing at the Gunston Arts Center, in Theatre Two – 2700 South Lang Street, in Arlington, VA. For tickets, call the box office at (703) 418-4808, or purchase them online.

LINKS:

Review: ‘The Gospel at Colonus’ at Avant Bard by Julia Hurley.

In the Moment: Q&A With Bob Telson, Composer of The Gospel at Colonus – Now Playing at Avant Bard by David Siegel.