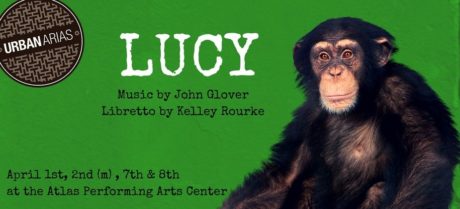

As the PETA-hounded circus left town on its farewell tour, I headed to the Atlas Performing Center to see Lucy, an UrbanArias opera about an actual chimp. I was reassured to learn that no animals were harmed in the production. In fact, throughout the oddly enjoyable hour, the only primate onstage was a human—one whose resounding baritone related a stranger-than-fiction true story.

In 1964—in an experiment then called cross-fostering—a psychologist and his wife adopted a day-old chimpanzee whom they named Lucy and raised in their home as their daughter. That’s what they considered her, their daughter. And the psychologist formed with her a particularly deep emotional bond.

The psychologist and his wife had a biological son about the same age, whom they named Steve. As much as possible, the couple treated Lucy and Steve the same, as equally human. For eleven years Lucy lived in their household (longer than any other cross-fostering placement). As Lucy grew she got her own bedroom, a lockable concrete-and-steel enclosure equipped with child’s furnishings and a drain in the floor. And she would be let out to play throughout the house and romp on the couple’s ranch and even be introduced to occasional house guests.

Eventually Lucy’s hostility and aggression made keeping her a danger. The experiment had failed. Lucy was relocated to a sort of game preserve in Gambia where people taught her how to live like other chimpanzees. A few years later she fell prey to a grisly killing by poachers.

Now, if you were a writing and composing team, does a first-person account by that chimp-loving shrink sound like it would make…an opera? Hard to imagine, but that’s the notion that occurred to Composer John Glover and Librettist Kelley Rourke. They took this very sincere man’s memoir about these very offbeat events and made it musically and dramatically into a surprisingly funny, fascinating, and ultimately touching experience. You wouldn’t think it would work. You’d think audiences would go eww, weird. But Lucy leaves you going wow.

The opera is set after Lucy’s horrific death, in the concrete and steel room that was hers. Michael Locher, a place captured with stark authenticity by Set Designer Michael Locher. The floor even shows stains leading to the drain from when the chimp was cleaned up after. The stage is set with a child-size bed and chair, some storage boxes, a floor lamp Lucy may have tipped over, and a table on which a 60s-era cassette player, slide projector, and film projector are arrayed. (This equipment will be deftly deployed as audiovisual aids as the story unfolds.)

Andrew Wilkowske, whose character is named after the real Maurice Temerlin, enters from an upstage door and begins singing a score that is remarkably revealing of his inner emotional life. “Lucy, Lucy, Lucy, Lucy…” he pleads, as if this plaintive, dirgelike repetition would bring her back to him.

And there’s a lot of amusement in the show. Maurice’s singing of Lucy’s defecation habits was scatological humor of the finest sort. At another point he runs about the stage almost like Lucy might and plays a silly game of peekaboo with us as if with her. And there is a hilarious scene when Maurice, pouring whiskey into a tiny teapot then pouring himself a drink in a tiny teacup, tells us what a wonderful drinking companion Lucy was—at an age when it would have been wrong to drink with Steve.

Accompanying Wilkowske’s strong sung narration was the Inscape Chamber Orchestra—Robert Wood, UrbanArias’ founder, conducting Sandy Choi on violin, Hrant Parsamian on cello, Evan Ross Solomon on bass clarinet, and R. Timothy McReynolds on piano. I was struck by the intensity of emotion the orchestra conveyed as when Maurice repeats simply “she, she, she, she,” words that alone could never have borne such anguish. And alongside the grownup instrumentation, David Hanlon on toy piano provided the sweetly tinkling theme for Lucy.

Director Erik Pearson heads a production that pulls us into a human-interest story that could easily seem simply quirky but pits us face to face with quickening questions about who we are as humans. A most remarkable thing happens during Lucy. The character of Lucy comes to seem completely real. We get to know her and see her first through Maurice, of course, but at some point during the show—through the artful confluence of libretto, score, performance, and design—Lucy becomes real on her own. So much so that when she dies, so has a tragic heroine.

Running Time: One hour, with no intermission.

Lucy plays through April 8, 2017, at UrbanArias performing at The Paul Sprenger Theatre at Atlas Performing Arts Center – 1333 H Street NE, in Washington, DC. For tickets, call (202) 399-7993 ext. 2, or purchase them online.

https://www.facebook.com/urbanarias/?hc_ref=NEWSFEED&fref=nf