The French and the Russians evoke very different images in the American mind, but they have one thing in common: an affinity for each other’s culture. Many Russian writers and composers lived a good deal of their lives in Paris, and a number of French singers scored some of their biggest successes in Russia, particularly St. Petersburg.

Since Peter the Great, learning French was so prevalent in parts of Russian culture that Russian opera composers – including Sergei Prokofiev, in his huge opera of Tolstoy’s even more massive novel, War and Peace – would switch lines in the libretto from Russian to French to make a point about a character’s background, situation, or intent to impress others.

All of this was context for a clever and rich program by the Russian Chamber Art Society (“RCAS”) last Friday evening with the theme of Russians in Paris. Most of the program was designed around material originally sung by the long-lived French mezzo-soprano Pauline Viardot (1821-1910) and the male singer who is still the poster boy for the idea that a bass rather than a tenor can be a superstar, the Russian Feodor Chaliapin (1873-1938). All of it was also enjoyable on its own terms, thanks largely to the singing of American soprano Jennifer Casey Cabot and Russian-Israeli bass Denis Sedov.

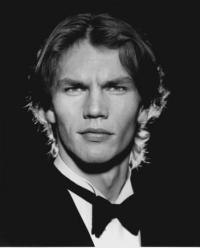

Material from both Russian and French opera formed the backbone of the concert. Mr. Sedov scored in Russian with “Aleko’s Cavatina” from Sergei Rachmaninoff’s little-known opera, Aleko, and in French with a key passage for the character of Mephistopheles from Charles Gounod’s big opera hit, Faust. Mr. Sedov’s very characterful approach worked great for the format of the RCAS events, where everyone gets a handout of all the translations but the best approach is to simply listen first, and then look later at the lyrics.

Hearing him sing in French was a treat, but I was really taken by the aria from Aleko. Composing the work was actually a student assignment for Rachmaninoff in the Moscow Conservatory and won him what was known as the “Great Gold Medal,” even though later in life he sniffed in disdain at his youthful opera. He shouldn’t have – just this season it was revived by New York City Opera. Aleko’s one-act structure enables it to serve as a refresher for a tired format where opera companies typically pair two Italian one-acts, Cavelleria Rusticana and Pagliacci, on a single evening. New York City Opera tossed out Cavelleria and put Aleko in its place.

Even in a concert setting, Mr. Sedov is well positioned to “play” the title character of Aleko. The character is an ethnic Russian who has fled civilization to become a gypsy and to find love, but who in a rage of jealously commits murder and is tossed out by gypsy society as well. As a true bass, Mr. Sedov can hit some shivering low D’s, but his additional strength is a gratifying shimmer with an occasional cry of emotion in higher ranges on lines that translate as “How the passions play with my obedient soul” and “Like a madman I kissed her enchanting eyes.”

Ms. Casey Cabot sang in Russian for “The Nightingale’s Aria” from Igor Stravinsky’s opera of The Nightingale (which actually got its premiere in Paris, much like Stravinsky’s ballets), and most significantly, “Natasha’s Aria” from Prokofiev’s War and Peace. You can tell that Ms. Casey Cabot often sings with big orchestras, including in such works as Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, from the way that her voice has a nice, even sustain over long notes and virtually perfect arched phrasing across rising and falling pitches.

Natasha’s Aria begins with a protest over her fiance’s family’s apparent intent to bar her marriage, but then releases into hope that he (Prince Andrei of War and Peace) will return from a year’s absence to convince his relatives. It’s a piece of storytelling that requires clear projection at various dynamic levels rather than a straight shot of soprano dramatics and hysterics. Ms. Casey-Cabot is clearly an operatic soprano that a theater audience could warm to. It’s worth noting that the RCAS events in general have, for a variety of reasons, a much more diverse – to be explicit, a younger on average – audience than many other presentations of classical music.

With that as an opportunity to broaden everyone’s horizons, I was especially pleased to hear Ms. Casey Cabot in a more specialized piece of Prokofiev music that has taken the stage before at RCAS – Five Poems of Anna Akhmatova. These miniatures are filled with nature and weather references, the sounds of footsteps and other interior noises, and references to memories and hopes that are surprisingly measured (and beautiful) for an ordinarily “spiky” and even sarcastic composer like Prokofiev.

I also wondered whether it would help or hurt to see a big photo above the RCAS stage of a young Prokofiev sitting rather smugly at a desk, peering forward as if to say to the performers, “Let’s see what you can do.” (Prokofiev was a rather confident and sometimes brusque man, as opposed to his slightly younger contemporary, Dmitri Shostakovich, who could be a nervous wreck.) Ms. Casey Cabot and the other performers seemed to find it inspiring rather than intimidating. Meanwhile, her big number in French was “The Jewel Song” from Faust. It had a bit less flash than some prominent sopranos provide it on the biggest opera stages, but her performance measured out well for the concert event.

All kinds of bonus extras filled the program designed by RCAS Founder and Artistic Director Vera Danchenko-Stern. I was a little nervous about a set of three pieces from the Prokofiev ballet Romeo and Juliet, played only by violinist Emil Chudnovsky with piano accompaniment. Mr. Chudnovsky proposed to dive right in with the “Dance of the Knights” (listed in the program under Prokofiev’s original name, “Montagues and Capulets”), which is a staple of even popular culture and TV commercials for its frank melodrama.

I wanted to know how a single fiddle could generate the energy of this piece, and Mr. Chudnovsky’s solution was fascinating. He split the relentless up-and-down motion across octaves, meaning halfway through a phrase he would jump to the equivalent note in a higher register of the violin, and then do a reverse jump down on the way back. Mr. Chudnovsky in general plays with a bit of bite and grain and situates his vibrato just below the exact center of the note, thus avoiding an overly “sweet” feel to this rather aggressive music.

And in case any attendees weren’t familiar with any of the rest of the material, they certainly knew the “Song of the Volga Boatmen,” championed long ago by Chaliapin and entertainingly presented in full bass sonority by Mr. Sedov. Just mentioning the opening line in English – “Yo, heave, ho, Yo, heave, ho” – probably puts the melody in your head, but getting it in the original Russian was even better.

The Russian Chamber Art Society has big plans. Its opening concert of the 2017-2018 season next October will be a gala at the French Embassy, featuring Washington, D.C. native and Metropolitan Opera star Denyce Graves singing material from The Queen of Spades by Tchaikovsky. If it’s anything like the last RCAS gala – an October 2016 presentation of highlights from Tchaikovsky’s other major opera, Eugene Onegin – it will be a unique introduction to an important work in an inspiring environment filled with fun, since the receptions after each RCAS event are basically a big party. It exemplifies the unique place that RCAS holds not only in the Washington cultural scene, but well beyond.

Running Time: 2 hours and 10 minutes, with one 15-minute intermission.

Russians in Paris played at the Russian Chamber Art Society on Friday, April 28, 2017 at La Maison Française, The Embassy of France – 4101 Reservoir Road, in Washington, DC. For a complete schedule and other information on the Russian Chamber Art Society, see their website.