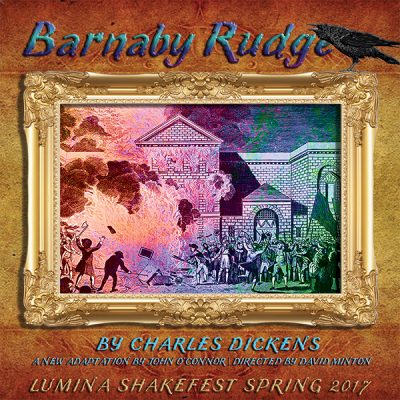

Of Charles Dickens’s fifteen novels, there are few, if any, that are less well-known than his first historical, Barnaby Rudge: A Tale of the Riots of Eighty—and few, with its forty-plus characters and complex plots and plotting, that would seem less likely to succeed as a play.

Adapted by John O’Connor, and in the capable hands of Director David Minton, who has a well-earned reputation for making the apparently impossible work as if born to, it not only succeeds as theater; it makes you want to go out and buy—or go back, and re-read—the book.

But: first things first.

The stage is nearly bare. What set there is, set upon gray cobblestone, is bare-bones simple: a small cot, a similarly near-miniature table and chair, and a small black mini proscenium with a black velvet curtain behind it (Set Design and Build: Jim Porter). Scenes will be minutes, sometimes seconds long, each introduced by scene-setting intertitles, sometimes descriptive, sometimes dryly humorous, projected on two video screens. Kudos to Video Archivist Kit Reiner and Videographer Ron Israel for these, and for the similarly inventive and thought-provoking signs that will be displayed throughout the play, as well as to Alexander Monsell for his Lighting Design, which sets the mood with lightning speed to match the corresponding situation and emotion.

We enter to the sound of pipes and strings. Barnaby Rudge (Jay Griffith), a large, fluffy black bird (Props: Jeff Streuwing) perched on his arm, awakens with a start from a nightmare and is comforted by his mother Mary (a quietly affecting Claudia Gryder). He vividly describes what he saw in his dream, the characters of which are introduced to us via the theatrical device known as traverse, or “tennis-court style” staging, the term introduced to those of us who may have seen it, but not known the name for it, by Minton’s edifying program notes. Griffith gives us an appealing Barnaby, whose eyes can widen in doe-like innocence or aching disbelief—and whose willingness and readiness to act on them, will shatter them.

Affixed to Barnaby’s arm (apparently accompanying him even in sleep) is a talkative, animated, uninhibited pet raven aptly named Grip (skillfully voiced by Jessa Nather), whose occasional ruffled-feather observations can be as pointed and penetrating as his sword-like black beak. As this is a political story set in a time of religious conflict, there may be the occasional temptation to see contemporaneity in its commentary. To which the tempting rejoinder may be . . . Get a Grip.

The music is a satisfyingly mood-setting medley of the classical and the English-Irish popular (Music Director: Wendy Lanxner), from 17th-century ballads to 18th-century symphony to 19th-century opera (though the last—Desdemona’s “Willow Song”—set in a story Verdi took from Shakespeare, might also be included among the first).

In strut (ten-hut!) two uniformed artillery officers, their Redcoat-red, gold-braided, jet-black-accented uniforms, military bearing and Brit accents spit-and-polish splendid. The romance of war, for young men who have yet to experience its reality, is stirring indeed. We shall meet these fellows later. (Their personal pot will be thoroughly stirred.)

Before that, though, we will meet Dolly Varden (Zenaida Alvarez-Brown), stirring a pot of her own as she confronts her father, the locksmith Gabriel Varden (Lauren Finlay). Alvarez-Brown offers a persuasive portrayal of a quietly determined young woman, her saucy self-confidence modulated with and undergirded by filial respect, ending in earnest appeals to reason, as Finlay’s Gabriel responds with an attempted firmness that begins to slide into capitulation, ending in an essentially kind and well-intentioned befuddlement.

As things progress, Dolly herself could be called befuddled, refusing to admit her true feelings for the man who loves her while at the same time being torn by them. Dolly’s confused despair will reach a heartrending apogee in this familiar but ever-poignant trope of the times that rarely fails to move. Alvarez-Brown’s absorbing, agonized awareness is all the more affecting because its subject—and object—himself unaware of it, remains unmoved.

As Martha Varden, Dolly’s mother and Gabriel’s wife, Gabriela Newburgh is a case-study in manic depression, her face flaming in anger, nearly matching her red curls, then drooping in ashen despondency. As her housemaid, Miggs, Willa Falvey gives her mistress a withering—and most satisfying—tit for tat. She will later display a flair for slapstick acrobatics that will leave you open-mouthed, midway between a gasp and a laugh, while the moral calisthenics of Gabriel Varden’s conceited and resentful apprentice Simon Tappertit (a lithe and slitheringly limber Isabel Echavarria), who also desires Dolly, may tend to conduce to the former, rather than the latter.

Just as Shakespeare’s Mistress Quickly had her Boar’s Head Tavern, which served as a location more for the enjoyment of libation than for the hatching of revolution, so Dickens’s John Willet has his Maypole Inn, where tales are told and strangers are quartered, the missing and mysterious the subject of boozy discourse. Though it may be lacking in plots, it will be the scene (and victim) of one’s aftermath. As the proprietor, Jacob Laas’s John Willet is eminently unlikable: proud, conceited, and intolerant of dissent or disobedience. His son Joe (Bridget Griffith) is the opposite of his father in motivation and conviction but his equal in temperament. Griffith gives us a complex portrait of a sensitive young man who will not be crushed, and who has the gumption not only to stand up to his father, but to employ it in the service of a higher cause.

There’s probably no lower cause than that of Hugh (Geffen Bendavid), the hostler of the Maypole Inn. Tall, angular, coarse and violent, his grotesquely gangly arms and unkempt dark hair hanging and swinging at cross-purposes with his galumphing stride, Hugh, in Bendavid’s dark and threatening portrayal, is yet no match for the dastardly Sir John, who will use him without compromise or compunction to his own evil ends.

At the other end of the social scale is, indeed, the reprehensible Sir John Chester, M.P. (a silkily supercilious and cat-like Ian Coursey) whose cavalier ease in command is surpassed only by the unrestrained pleasure he takes in watching his unfortunate inferiors grovel. Sir John is determined that his son Edward (Ingrid Ellis), who is in love with Emma Haredale (Isabel Ryan-Silva), the niece of his bitter enemy, Geoffrey Haredale (Grace Duggan), will marry into money, so as to both support Sir John’s lavish lifestyle and liquidate his extensive (and excessive) debt.

While Haredale is also imperious—in Duggan’s forceful portrayal we sense in him an injured dignity, a challenge to the man’s honor that will not go unmet—he is the moral mirror image of Sir John. So too his niece, whose sweetness is epitomized by her dress and physiognomy, her Kewpie-doll lips a brilliant red, her cheeks each with a quarter-sized rouge-spot, the picture completed with a tight-waisted chiffon ball gown of white and baby blue (Make-up Design: Liz Porter; Costumers: Wendy Eck and Dianne Dumais). Ryan-Silva humorously plays off Newburgh’s Martha Varden: two more unalike women you will rarely find; yet their encounter, as those between other characters we think we know, will not turn out as we might expect.

This being an adaptation of a novel whose subtitle is A Tale of the Riots of Eighty, there must needs be more here than enactments of human travail. Here, too, Lumina delivers, making the most of its limited resources so that the crowd of Protestants railing against Papists sounds as loud and rowdy as a thousand-strong rally railing against Trumpists (Video & Sound Engineer: Ron Murphy). But this is a horde with more on its mind: the Gordon Riots of 1780 began as a demonstration, seeking a redress of grievances, but—as demonstrations without direction and leadership are inclined to do—progressed to a point of no return. To emphasize the ineffectuality of the political order, there’s even a Mayor (an utterly indifferent, sleazily self-interested Gabe Hoekman) who, Pilate-like, washes his hands of the matter upon being desperately importuned by three demonstrators (who are quite impressive in their brief time onstage).

As it disperses, we return to Lord George and his secretary; as Gashford, Maxine DeVeaux is the ultimate suck-up. We also encounter Stagg; Lily Creekmore’s portrayal of the crafty blind man is so attuned to the nuances of a sightless individual’s mindful maneuvers and preternatural cognizance of imminent dangers, our eyes are fixed on the character’s every hesitant step, his gingerly tap-tap of the cane; and yet—knowing he’s a villain—almost hoping he will fall.

As always in Lumina productions, there are the small fry, whose intermittent appearance as “Read all about it!” newsboys gleefully shouting out polysyllabic, intricately composed headline puns, printed on signs they proudly thrust out and hold up, is as skillful as it is adorable. The signs themselves go from the Colbert-worthy to the groan-worthy, making their incongruous presentation by rosy-cheeked cherubs irresistibly squeeze-worthy. By combining the sophisticated with the innocent, the historical with the hysterical, the provocative with the thought-provoking, David Minton and his company have once again produced a show that is eminently see-worthy.

Running Time: Three hours, including one 20-minute intermission.

Barnaby Rudge plays through May 14, 2017, at Lumina Studio Theatre performing at The Silver Spring Black Box Theater– 8641 Colesville Road, in Silver Spring, MD. The play is performed by two casts. For tickets, purchase them online for the PLUM Cast or the RED Cast.