“Games have rules,” Brooklyn-parent Dixon (Zach Brewster-Geisz) tells his wife, Pam (Mindy Shaw). They’re playing Boggle, Dixon has tried to play “Slurpee,” and both are a little wounded that their 16-year-old daughter, Julie (Ruthie Rado) has lied to them.

Games have rules, and family relations are sometimes best understood as a game we sometimes agree to play together. Julie’s parents believe that the rules of their family’s game is: no lying. And yet.

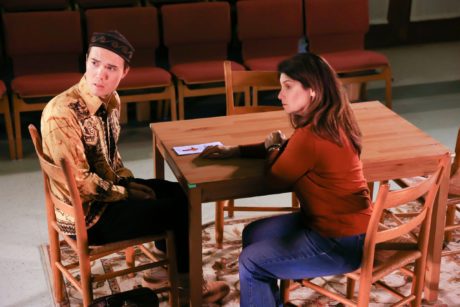

Julie’s lie: she didn’t go on a campus tour of Wesleyan in Connecticut. She went, instead, with her friend, Bernard (Jonathan Frye) to a religious retreat in Teaneck, New Jersey. She knows her parents aren’t going to handle it well (her father is a secular Jew who smokes weed; her mother a staunch atheist documentarian filmmaker whom I promise you’ve stood behind at least once in your life at a Whole Foods and she was buying fennel), which is why Julie is keeping her conversion narrative a secret. It turns out, another rule of this household is: Thou shalt not convert.

Because secrets always have a way of bubbling up and out on a stage – and because secrets almost never travel alone, but in pairs or groups, for maximum effect and safety – Carly Mensch’s Oblivion explores this ripple effect of lying and rules, both on this family, and on the idea of “truth” itself.

Unexpected Stage Company’s production is wonderfully unexpected and lovingly staged in the basement of a Unitarian church in Bethesda – which is Montgomery County’s version of Brooklyn, if we’re being honest, and we are: they’re getting rid of a bookstore to set up a three-story Anthropologie, for instance and to back up my claim. Everything from Kristen Jepperson’s wonderful and economic set design (in a fully-inhabited three-quarter staging that gives us not only the family’s living room and kitchen, but also becomes the laundry room, a church, a sound stage, and a rooftop baptismal); to Andrew Dodge’s lighting (for example, allowing Bernard, Julie’s friend, space at several moments in the play for contemplative conversations with his own version of God, the acerbic film critic Pauline Kael, whose review of Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs I can almost recite from memory I love its laser-focused takedown so much); to the lovely and thoughtfully curated music cues that punctuate the action; anchor the audience solidly in a world that, while not always believable (an issue more with Mensch’s script than this very good production), feels entirely lived in. If I don’t always believe in each of the family member’s specific actions (and more on that in a minute), I wholeheartedly believe in this family.

Christopher Goodrich, Oblivion’s director and Co-Founder of Unexpected Stage Company, has given this play a lot of thought, which comes through in the strong performances he gets from his actors. This play is peopled with characters who need us to love them while, at the same time, finding themselves in unlovely poses: of bigotry, of pained self-doubt, of dawning self-awareness, and daytime unemployment pajamas. Goodrich’s direction is sensitive to this tension, and the play is stronger than some of its weaker-written moments, because of him. If there’s anything to tweak at all, it might be the pacing. Mensch is primarily a television writer, and there’s a speedier cadence to that kind of delivery. Picking the dialogue up a notch or two would also allow those purposeful moments of cringe-inducing silence to land. (Having said that, I will say that one of the funniest moments in this play for me was the slooooowest conversation-avoiding drink of water I’ve seen in awhile. It’s a brilliant bit of comedy from Frye’s Bernard.)

The cast is incredibly strong – and when you’re only going to have four people on stage, there really isn’t a lot of luxury for a background player. Goodrich, in his program notes, talks about the intimacy inherent in smaller theaters, how both the actors and the audience are confronted with the challenges of honesty. When we’re this close – practically in the family’s living room – there isn’t room for cheats and tricks from the actors. And, likewise, the actors can see what all of our faces are doing. In a play this concerned with the uses and abuses of dishonesty, this unexpected scene work between actor and audience is a little thrilling, and, because of how great all of these actors are, richly rewarding.

Ruthie Rado’s Julie is a perfect realization of that specific kind of adolescent precociousness. She’s above it all, the way every world-weary 16-year-old is above it all (how burdensome the knowledge of everything is at that age); but she’s also vulnerable about how much she thinks she knows. Watching Rado portray Julie’s gradual acceptance of doubt is a large part of what makes this production so successful.

Brewster-Geisz’s Dixon is a man plagued by doubt, too. Our forties, today, have newly become that area of the map labeled “here be monsters.” Where 40 used to have the performative patina of authority – adults are 40, and adults have it all figured out – 40 is now mostly a refrain of the tail-end of our 20s. Dixon discovers this, in his pajamas, after leaving a job as a high-powered attorney. There’s a young, pal quality to Brewster-Geisz’s understanding of Dixon – he’s a lost adolescent, too, whether he’s offering weed to a teenager, or writing erotic fan fiction about a French ambassador’s daughter. Brewster-Geisz is charming and hurt, silly and, ultimately, the one with the clearest understanding of what adulthood is: effing up again and again, because that’s what it means to be human.

(One problem this script has is specific to how Dixon is handled. There’s a revelation, later in the play, when secrets start spilling out of almost everyone, that doesn’t fit well within the story Mensch is telling. It undermines Dixon in an unfair way that, in all honesty, I’ve chosen to ignore in thinking about Dixon.)

Shaw’s Pam is a fascinating creation. We sympathize with her as the only adult in a house of adolescents. Shaw gives Pam so much care and compassion right up until her worldview is challenged. That “here be monsters” map I mentioned, for Dixon, is Pam’s map too. She finds herself one of those monsters, where it’s gradually revealed to her how much her tolerance of others is based in how much she doesn’t have to exercise it. Agree with Pam and she agrees with you. Challenge her point of view, circle around what she knows to be right, however, and you’ll have quickly reached the end of Pam’s known universe. Shaw is so watchable because of the deep understanding she brings to this character.

(“I never lie,” Pam says, early in the play, and I wish, at some point, Mensch’s script took a moment to call her out on this. It’s a clear falsehood. The play finds time to allow each character to hear the truth about herself; I wish it found time to give Pam that opportunity, specifically challenging and correcting her understanding of what honesty and lying really are. Pam wields the truth like it is some kind of weapon, but we never see her suffer any recoil from her shots.)

Frye gives Bernard a specific kind of awkward anxiety that any of us should recognize. Oblivion isn’t interested in the existence of God, but in what belief of any kind offers. Watching Frye give life to Bernard’s journey from extolling the gospel of Pauline Kael (privately, to himself, in beautifully lit monologues) to feeling betrayed by this embodiment of his God – discovering her weaknesses and limitations – to a touching reconciliation with Pauline Kael by the play’s end is another way this play rewards an audience.

A lot of truth is just a lie you’ve learned to live with. “I know what I’m doing.” “Our marriage is solid.” “Pauline Kael can do no wrong.” Unexpected Stage Company’s production of Oblivion does a wonderful job of exploring this idea, and is well worth your time and attention. See it if you can.

Running time: 2 hours, with a 15-minute intermission.

Oblivion plays through August 6, 2017, at Unexpected Stage Company performing at River Road Unitarian Universalist Congregation Building – 6301 River Road, in Bethesda, MD. For tickets, buy them at the door, or purchase them online.