On August 11th and 12th, a group of neo-Nazis, fascists, and white supremacists thronged Charlottesville, Virginia. They were there to protest – peacefully, they’d said – the removal of a statue of Robert E. Lee. But the rally in the city I called home for four years wasn’t peaceful. Fascists killed a woman, beat an unarmed black man, and struck my friends with lit torches.

Nearly a month later, those of us who have loved and lived in Charlottesville are still reckoning with the pain the rally caused. I have thought of what I saw on the 12th – state police trucks rolling through the Downtown Mall, protesters weeping because they’d just seen Heather Heyer die – and then, as I so often do, I thought of theater.

In July, I saw the Wandering Theatre Company’s production of The Laramie Project for the Capital Fringe Festival. The Laramie Project is documented theater: the script draws on verbatim interviews with the citizens of Laramie, where a gay man, Matthew Shepard, was brutally murdered in 1998. One of the characters tells the audience, “Someone said… ‘c’mon guys, let’s show the world that Laramie is not this kind of town.’ But it is that kind of town. If it wasn’t this kind of a town, why did this happen here? We need to own this crime. We are like this. We ARE like this. WE are LIKE this.”

We are like this, Charlottesville. And theater may be the best way of acknowledging that fact. But it can’t just be any kind of theater – it must be cognizant of the minority voices that Charlottesville has minimized, both intentionally and unintentionally, since the city was founded.

“Theater has a place in this [post-rally] dialogue,” said Leslie Scott-Jones, director of the August Wilson play Jitney for the African-American Heritage Center. “Art has always been the way that people’s minds have changed. Because art touches people’s hearts. It can show you a perspective that you don’t live in a way that nothing else can. That’s the most sacred duty that any artist has, to tell that truth.”

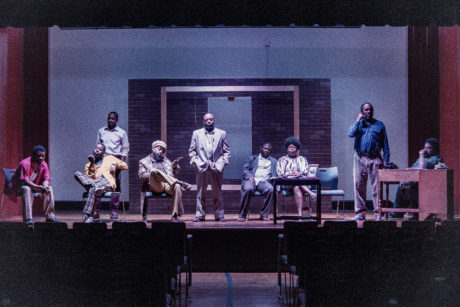

That sacred truth is something that Paul Robeson Players, a black theater group at UVA, is committed to. “We were revived in 2010 to provide a space for black theater to happen,” said Roberto Thomas, a fourth-year student and president of the organization. “But we also liked the idea of responding to political injustices. Ours is revolutionary theater. We respond to whatever impacts our community.”

Paul Robeson Players has recently taken co-ownership of The Black Monologues, a show that is written, produced, directed, and acted by UVA students of color. When The Black Monologues premiered in 2015, the show was a smash hit. Paul Robeson Players and the UVA Department of Drama now plan to put it on every year.

Ali Cheraghpour, a fourth-year and president of student theater group Shakespeare on the Lawn, has also been thinking about how to respond to the injustice of the rally. “Jessica Williams [of 2 Dope Queens and The Daily Show] came here to speak recently,” Cheraghpour told me. “She said, ‘If you’re black, if you’re gay, if you’re Muslim, if you’re Jewish…take the pain, the anger, and the sadness and turn it into art.’ Those words resonated with me.” Cheraghpour, who is a master of turning his emotion into art, directed a production of The Importance of Being Earnest last year. Now, he leads the organization that Richard Spencer joined while he was a student at UVA.

Spencer is president of the National Policy Institute, a white supremacist think tank, and was to be one of the headline speakers at the rally in August. He graduated from UVA in 2001, during the earliest days of Shakespeare on the Lawn.

The connection between Spencer and Shakespeare on the Lawn is not lost on Cheraghpour. “I plan to denounce [Spencer’s] ideology during our first general meeting,” he told me. “I can’t erase the fact that he was a part of Shakespeare on the Lawn. He was. The theater community at UVA has a high population of white people, and Shakespeare on the Lawn is an example of that.”

Even though Cheraghpour has felt welcomed by UVA student theater, he said, he still feels the lack of diversity keenly. “I’m Iranian. My parents are both immigrants, and our whole family’s Muslim. One day [shortly after the rally], I was very scared. My blinds were up, and I had a Koran visible in my room. I had this thought: ‘Maybe I should hide this. What if the wrong person sees this and they think that whoever’s living here is a target?’”

Cheraghpour, who describes himself as ‘Muslim-ish,’ has recently begun to study the Koran so that he can embody the faith of his parents. For him, being Muslim is about being a good person. But he doesn’t know many other Muslims involved in theater at UVA – or many non-white thespians at all. That lack of diversity has troubled Cheraghpour for a long time.

Racial and ethnic homogeneity doesn’t just exist on UVA’s Grounds. “We’re doing black theater in a place that isn’t used to seeing black theater,” said Scott-Jones. Like almost all the plays in August Wilson’s ten-part Pittsburgh Cycle, Jitney has an entirely black cast of characters. “In the past, Charlottesville’s idea of black theater has been a single play with a black character in it.”

Scott-Jones and other black thespians (including Clinton Johnston, who directed Wilson’s Fences earlier this year) have dedicated themselves to bringing Wilson’s entire cycle to the Charlottesville community. The reason: Black directors and actors have few opportunities to help bring to life stories with which they can truly connect.

Charlottesville may be a small town, said Scott-Jones, but it doesn’t have a small appetite for African American theater. “The response to Fences was amazing. Our last night, we had to add chairs. We were blown away by how not just the black community, but the entire community of Charlottesville supported us.”

After August 12th, however, the African-American Heritage Center’s production of The Pittsburgh Cycle plays took on new meaning. Part of that meaning came from the rally’s violent rhetoric against people of color. Several cast members protested that day, and their bravery reminded Scott-Jones of the plot of Jitney. In the show, gentrification nearly drives unlicensed cab drivers, or ‘jitneys,’ out of Pittsburgh’s Hill District. The drivers band together and refuse to let the cab office close, even though the building has been condemned.

“The drivers’ defiance took on more meaning for me after August 12th,” said Scott-Jones. In that way, she told me, the rally and counter-protest will be a part of the show.

The rally came at a charged moment for the cast and crew of UVA Department of Drama’s fall production, WE ARE PUSSY RIOT OR EVERYTHING IS P.R. Like The Laramie Project, WE ARE PUSSY RIOT (by Barbara Hammond) tells a true story, this time of the Russian feminist band who staged a protest in Moscow’s Cathedral of Christ the Savior. Two members were eventually arrested for ‘hooliganism motivated by religious hatred’ and served two-year sentences.

“The nature of protest theatre, and this particular Pussy Riot incident, might resonate with our local community because we still have the weekend of August 11-12 at our forefront of attention,” said Marianne Kubik, director and UVA professor.

Kubik said that she and her creative team are carefully considering the audience-interactive piece’s effect on its audience. Though the clashes in WE ARE PUSSY RIOT and Charlottesville are distinct – one a feminist protest against Vladimir Putin and the Russian church, one a white supremacist protest against the decision of a local government – they both provoked worldwide outrage and a re-examination of community values.

For Thomas, too, the rally has meant new dialogue – but not one foreign to him. “The rally was horrible, but the reality is that these kinds of events aren’t new for many people. This is not a shock. It’s just that the rally threw it in everyone’s face, which sparked a conversation.”

That conversation, he said, can be accomplished through theater. Shows like The Laramie Project, which carry a clear social message, create connections unlike any other between audience and performer. “In theater,” Thomas said, “you can perform your perspective of what happened, and you use that to relate to people.”

Charlottesville is the kind of town where white supremacist rallies happen. It is like that. But it will also play host to Jitney, to The Black Monologues, and to shows Cheraghpour can help oversee. In those productions and others, the community has a chance to speak from the heart, with as many voices as there are actors to give them breath. Theater is art, but it’s also a tool for facilitating conversation.

Additionally, Charlottesville’s statue of Lee is now shrouded. But Scott-Jones hopes that the city could one day be the home of a different statue.

“Someone asked me, ‘What would you replace the Lee statue with?’ I answered that I’d want it replaced with a statue of Queen Charlotte,” said Scott-Jones, referring to Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, Queen of England from 1761 to 1818. Charlottesville was founded in 1762 and took its name from England’s new queen, who was descended from Madragana, a Portuguese Moor.

“Charlotte was royalty. She was black. She gave George fifteen children. She was a botanist and a musician and adored the arts. That’s a much more powerful statement for a statue.”

An image of Charlotte is, I think, much more fitting than that of a soldier who lost. For a city in need of beauty and healing and honest conversation, Charlotte symbolizes the power of art, especially art created in the face of violence.

And that, said Scott-Jones, is the most radical act there is.

LINK:

2017 Capital Fringe Review: ‘The Laramie Project’ by Ravelle Brickman.

An excellent article, beautifully written & refreshing. For the last 17 years I have been using theater as a vehicle for social change with my One Man show on Paul Robeson. I’m a Jamaican born, Brooklyn bred actor of Kenyan Ancestry who also is a moderate Muslim. Ali Cheraghpour story spoke to me as well as those in the group. I would love to contact the Robeson players and offer them a Benefit show of my play. The website is paulrobesononemanshow.com and I will be in Virginia performing in Newport News, at the Ella Fitgerald Performing Arts Center on Sept. 29th

Wishing you Love & Light.

Peace & Progress

Stogie Kenyatta

Thanks so much for your comment, Stogie. The article links to Charlottesville’s Paul Robeson Players’ Facebook page. I’ve alerted them to your comment but you can also IM them there to get in touch. Best, Nicole