In a recent satire published on Medium, the San Francisco writer/actor/comedian Alison Page listed five dozen “Honest Theatre Awards.” Among them was one that struck me as an apt accolade for the production of The Arsonists I had just attended at Woolly Mammoth: “The This-Play-Isn’t-About-Trump-But-It-Kind-Of-Is-Now Award.”

As if to underscore The Arsonists‘ earnest eligibility in that joke category, Director Michael John Garcés has a wide flat-screen television upstage showing a montage of recognizable current-events footage including multiple shots of POTUS. The TV, situated in the home of the main character, George Betterman, plays constantly, through scene after scene in which neither it nor what’s on it is ever referenced. It’s just there, incessantly.

At first glance, this might seem a fundamental directorial mistake: a running distraction that keeps pulling focus from the actors and that the play doesn’t call for. Like having a pile of cuddly puppies on the set during Hamlet because the director wants us to consider how the Dane is really great. But of course, the TV in The Arsonists has more pertinence than that, for we are obviously meant to stay mindful of how what’s playing out on the nightly news is the frame through which we ought to be interpreting the Max Frisch script from seven decades ago.

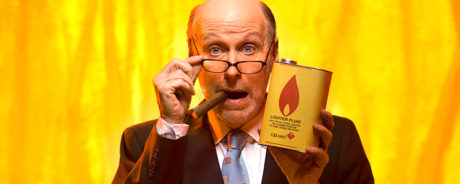

The play is about an Everyman (named Biedermann in the original German, Betterman in this translation) who lives in a town where, as reported in the local newspaper, there have been alarming outbreaks of fire set by clandestine arsonists who inveigle themselves into people’s home. When strangers show up at Betterman’s door and ask for food and lodging, he, wanting to appear a good guy, permits them to sleep in his attic—unaware that they too are arsonists who will shortly stockpile ominous drums of gasoline there. The script has much to say about Betterman’s passive complicity, and (to no one’s surprise) the gasoline is ignited and a conflagration ensues. The twist is who offers the arsonists the match: it’s none other than Betterman, whose incapacity for critical thinking the play makes an excoriating example of.

The play was written as a cautionary allegory about ordinary citizens’ collateral guilt in the rise of Fascism and Nazism, one of several post-World War II plays to try to make sense of the senseless. Thus the message in The Arsonists is spelled out not only in the fable-like storyline but in some astute aphorisms, sharply translated by Alistair Beaton, sprinkled throughout, often in the voices of a chorus of firefighter/watchers. A couple of my favorites were these:

If the thought of radical change scares you more than disaster, what can be done to stop the disaster?

And

We fail to see what’s happening under our noses.

The script veers toward the sententious, but that comes with the political-parable territory in such post-war dramatists as Frisch, Brecht, and Dürrenmatt. And the antic and energetic acting style adopted for the Woolly production prevents the text from ever seeming tendentious.

A program note explains that Woolly’s decision to program The Arsonists this season had a fire lit under it, so to speak, with the November 2016 election. On the face of it, this work would seem a felicitous choice. The Arsonists is about impending political danger and individual responsibility to take collective action that would intervene and stop it. Additionally, with substantial foundation support, Woolly embarked on an extraordinary community-partnership and audience-engagement effort surrounding the run, offering, for instance, talkbacks during which folks who’ve just seen the show can process what it meant to them.

As the audience leaves the theater, actors hand out a flyer printed on flame-red paper that makes the show’s point explicit:

It can happen here. We can stop it.

I found this all good and worthy…except the production did not actually do what it was intended to do. The passive-observer mode elicited by that always-on flat-screen television became the expected point of view from which to take in the whole show—a misfire effect compounded near the end by a whiz-bang display of stagecraft that left one going gosh-wow! more than OMG what can I do? The actors—evidently skilled even as they gamely played as over the top as they were supposed to—were never really given the sort of relatable moments that would connect us to their moral quandary emotionally other than as abstract, detached contemplation.

Perhaps in the way the production more numbed me than mobilized me, it was more about Trump than I thought.

Running Time: 2 hours without an intermission.

The Arsonists plays through October 8 at Woolly Mammoth Theatre Company – 641 D Street, NW, in Washington, DC. For tickets, call the box office at (202) 393-3939 or purchase them online.

LINK:

Review: ‘The Arsonists’ at Woolly Mammoth Theatre Company by