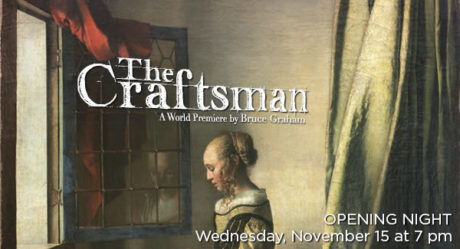

Philadelphia theater-goers have something extra to be thankful for this Thanksgiving month. Bruce Graham’s latest play The Craftsman, commissioned and developed through Lantern Theater Company’s New Works Initiative (as mentioned in my last interview with Graham in May 2016), will begin previews on November 9. The subject is one that has fascinated the Lantern’s Co-Founding Artistic Director Charles McMahon for decades (as it has me, with a PhD in Dutch Baroque Art): the real-life story of artist and art dealer Han van Meegeren’s forgery of paintings attributed to the 17th-century Dutch master Jan Vermeer, which he created during World War II and sold to the Nazis. Because Vermeer’s works are registered as National Treasures of The Netherlands, and because the country fought on the side of the Allies as a key player in the Nazi Resistance (a fact made famous in The Diary of Anne Frank), the act – considered treason for consorting with the enemy – was punishable by death, were the charges proven and van Meegeren found guilty.

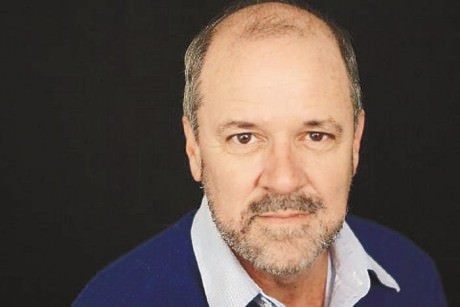

The Lantern has put together a roster of Philadelphia-theater treasures for the world-premiere production. Along with the city’s preeminent playwright and the highly-acclaimed actor Ian Merrill Peakes (both making their Lantern debuts), the team includes a cast of Lantern favorites Mary Lee Bednarek, Anthony Lawton, Dan Hodge, Brian McCann, and Paul L. Nolan, and the top-notch design team of Christopher Colucci, Meghan Jones, Janelle Kauffman, Kayla Speedy, and Shannon Zura, under the skilled direction of company Education Director M. Craig Getting.

I was invited to attend a rehearsal of the show and to discuss the play with Charles and Bruce, which I did on October 31 – the date of Vermeer’s birth in 1632.

Deb: When did you first become interested in the van Meegeren forgeries and decide to produce a play on the subject?

Charles: I attended a talk at the Penn Museum in 1998, I believe, by British director, author, and neurologist Jonathan Miller, about how your frame of reference affects how you see something. When I first saw the images by van Meegeren, I couldn’t believe anyone was fooled by them; they look nothing like real Vermeer paintings!

Bruce: As soon as I saw the paintings, I thought the same thing. I couldn’t believe people bought this! In the production we’ll include projections of paintings by Vermeer and the forgeries by van Meegeren, so the audience can see and decide for themselves how different or similar they think they look. We all have our own viewpoints and aesthetic.

Charles: Miller suggested that van Meegeren could get away with the forgeries because in his period of the 1930s, there was an agreement about what factors constituted a Vermeer, elements that everyone recognized. He was a part of that world, so he absorbed it. But the definition of what is ‘Vermeerness’ might change in the context of different generations; it’s all about the viewer’s frame of reference. I could relate to that, because at the time I was reading different translations of Ibsen, which changed with each decade; they spoil like old milk! I had trouble picking the one that would be the most authentic, so the concept of “frame of reference” was of great interest to me.

What was it about the real-life events that appealed to you as the basis for a play?

Charles: For me it was the psychological motivation for believing in falsehood, and the aspect of group-think. Once van Meegeren’s forgeries were accepted by Abraham Bredius, the leading expert of the time, it didn’t matter what they looked like; the universal mentality is “I don’t want to know the truth.” Then, retroactively, people suddenly discern that it’s not true and it’s shattering, so they’d rather disbelieve the evidence and the pedestrian reality, rather than the implausible story, which is more interesting and exciting. It also questions the intersection of what’s authenticity and what’s authority, what is real art, what is genius, and what is just a craftsman’s skill; is there a difference? Those were the intellectual kernels that interested me.

Bruce: There are so many interesting themes that revolve around this story, especially because it’s all done in the context of such high stakes. It’s clear that there were some deep motivations there that go beyond mere ambition and greed.

When and why did you ask Bruce to write the play for the Lantern?

Charles: I’ve always loved his work, so early last year I asked him how his schedule looked and we talked about the ideas I had. He loved it, because the guy’s a conman who goes big to hoodwink the experts, so he was interested from the beginning. Bruce respects the psychology of the downtrodden guy, the pathology of having no resistance to temptation, the irony of a liar telling the truth, and the ultimate question of what is truth? I didn’t write the play myself because what interested me were the abstractions, whereas Bruce’s angle is always the most dramatic.

Without giving too much of the story away, what are the main plot points emphasized in the script?

Charles: Ultimately what makes this story work is that Bruce focused on the conman aspect and the psychology of the human motivation for believing in falsehoods. Van Meegeren tells the simple truth, but people are hesitant to accept it, because one expert, in this case Bredius (played by Paul), can get everyone to believe a lie. What are the facts? The irony is that it takes a conman to identify that, once he gets caught, and then popular opinion falls like dominoes. Structurally, Bruce’s telling revolves around van Meegeren’s trial, injecting into it the aspect of a nation hopping mad and out for blood, in an attempt to purge their country of the specter of the Nazis in the aftermath of World War II.

The cast for the show is nothing short of stellar. Did you have these specific actors in mind for their roles from the beginning of the process, or did you hold auditions?

Charles: We held auditions. With a new play by Bruce Graham, we were certain that we could attract great talent, and our pay scale now is very competitive with the salaries of the top-tier big-budget companies. It was an open call, with union actors given first crack, and then non-union afterwards, for about three days. There were a few people we were really hoping would be available; Ian and Tony were high on that list, in the most pivotal roles in the play. While the story is centered around Tony’s character, the emotional journey of Ian’s character drives the story in the way that Bruce has framed it; the nuance and subtlety that he brings to Pillel’s development are key to the story, and of course he does it brilliantly. The rest of the cast has worked with us before, so we knew we were making good choices with all of them, as well.

At what point did you decide to hand the show over to Craig to direct, instead of doing it yourself?

Charles: I’m interested in our company telling great stories, and I’m confident in our team to do it, so I didn’t need to direct. Bruce has put a great story on the page, and Craig has grown and progressed since he’s been with us. We’ve been giving him bigger and bigger projects, so I knew he was more than capable of handling this one. He’s very meticulous, analytical, and detail oriented, but he doesn’t get stuck, he’s good at prioritizing. Throughout our history, we’ve gotten great rewards back from giving our young directors major productions and challenges.

As Artistic Director, were you still involved in much of the process in terms of development and design?

Charles: I was more involved in the early stages, in giving notes, but I try not to interfere. There are big character reversals in the second act, invested with feelings and meaning; those things change through the rehearsal process. Plus at the end of the play, there is antagonism, but it’s not obvious; it’s a subtle combination of hate and the need for approval. We’ve discussed the mechanics of a few scenes, but it was more about the scale and proportion of things. Meghan Jones is a wonderful Scenic Designer and she’s very accomplished at solving the problem of a unit set in our odd L-shaped space, which she’s done many times before. Chris Colucci is doing the sound and Shannon Zura the lighting, so it’s been important for them to watch how the story unfolds, as have I, but my role at this point is to let these trusted artists work, and then I just give my impressions.

I know Bruce has been a presence at the readings and rehearsals, and has made some adjustments to the script. What is the tone you’re going for – straight drama or dark comedy?

Bruce: We had three readings with small audiences to see what worked and what didn’t. Right now I’m on my eleventh version of the script, tracking the evolution of the characters to make sure the audience buys it. I’m also being very careful about my word choices, so that it’s true to the language of art and of the period. The subject is different from the plays I usually do, which are set in America, mostly in Philadelphia, though I have done period pieces before – of old Hollywood, but not of European history. I did a lot of research for this. I read five books on the subject of the painters, to make sure I had the background and the characteristics; then I felt more comfortable with setting the dramatic tone and seeing the sardonic irony of van Meegeren’s story.

Charles: It’s a darkly funny straight drama of characters on the edge, at monumental risk, which results in some elements of gallows humor. One example is the secular creed of Dan’s character Boll. He has professional integrity, he’s serious about the letter of the law and doing it by the book, but personally he doesn’t have the same high moral code in his comments about van Meegeren’s attractive wife Johanna (played by Mary Lee), which leads to Pillel’s most darkly comic line. It’s funny and horrifying at the same time.

After the world premiere at the Lantern, is there any interest in traveling the show to New York, Chicago, or maybe even The Netherlands?

Charles: Bruce has the rights, we’re the commissioning organization, but yes, I would be interested in seeing it launched. As Bruce said, this is a theme that is not specific to Philadelphia, it could play anywhere, with its subject of Vermeer and the aftermath of World War II. But it’s different from other WWII dramas, in that it’s not rooted in smoking out the Nazis for trial, but in examining the psychological effects of the War on a shattered country and the citizens who suffered through it. That’s not told as often as other types of WWII stories, but audiences everywhere know the context.

Bruce: Yeah, wherever it lands is great with me. I’m usually hands off and not that involved with these kinds of things. Director Jim Christy once told me that I’m “the closest there is to a dead playwright.”

Is there a specific target audience you’re aiming for, or does it hold appeal and a significant message for everyone? What are the takeaways from the real-life events portrayed in the show?

Charles: I generally think most of our work has a sort of obvious audience, though they’re not necessarily the majority of people who come. A lot of people will come to this for the art, the history, and the pathological psychology, but everyone who loves a fabulous story should also see it. It’s very suspenseful, a real story written as fiction, so I expect it to have a wide crossover appeal.

Many thanks, Charles and Bruce; I look forward to seeing the full-stage production, as should Philadelphia audiences!

The Craftsman plays through Sunday, December 10, 2017, at Lantern Theater Company, performing at St. Stephen’s Theater – 923 Ludlow Street, Philadelphia, PA. For tickets, call (215) 829-0395, or purchase them online.

Great news: we have extended! THE CRAFTSMAN will now close on Sunday, December 17. http://www.lanterntheater.org