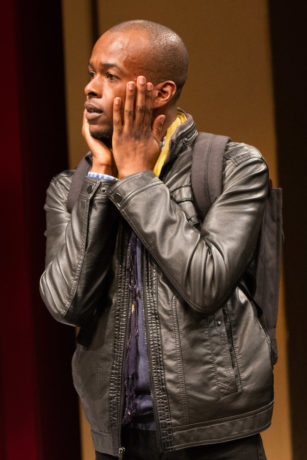

Justin Weaks was recently named by the Washington Post one of DMV’s 12 “stage dynamos,” one of “the best of an emerging cadre of younger regional talent.” He would have been on my short list too. I’ve been impressed with his work in the seven plays I’ve seen him in, and I can now add to that list his intense and moving performance in Curve of Departure, which just opened at Studio Theatre.

Curve of Departure by Rachel Bonds—exquisitely directed by Mike Donahue—is a beautiful and funny tearjerker of a family drama. It’s about four good people trying to find their way. They’ve met in a hotel room in Santa Fe for a funeral. Justin plays Felix the gay son. Ora Jones plays Linda his mother. Peter Van Wagner plays Rudy his grandfather. And Sebastian Arboleda plays Jackson his boyfriend.

Shortly before Curve of Departure opened, I sat down with Justin at Studio and talked about his DC acting career to date and his role in this wonderful play.

John: What goes through your mind when you are applauded, or when your work is acclaimed?

It’s very lovely to get kind words from people. It’s always nice to be applauded. Very humbling. But it’s about the work. It’s not about the accolades and the praise.

Who are your role models—actors whose lives and bodies of work you admire?

I grew up watching Sidney Poitier and Denzel Washington. A lot of Whoopi Goldberg. And Tom Hanks. I’ve become a big fan of David Oyelowo’s work—he played MLK in Selma. I’m a big fan of chameleons—actors who transform themselves and aren’t confined to one box of things to do.

Why acting? Why theater? What got you hooked?

I was a gymnast for a long time, and that definitely has performance elements to it. You get on the floor to do your routine and it’s your time on the stage. I’ve always loved performing. I got bit by the bug around eleven. I was doing a play for an elementary school audience, a kind of Commedia-inspired production. At first, it was a chance to be seen. And then the older I got, it gave me a chance to hide. In the environment that I was educated in, on top of where I was growing up, I didn’t always feel free or safe to be who I fully was or to fully express who I was. And that’s hard as a young person, trying to find your way when everyone else is trying to fit you in a mold. And so it became a chance for me to have a protective cloak on when I was on stage. The theater gave me the chance to feel whatever I was feeling without apology and to say how I felt without repercussion.

I’ve seen you now in seven roles, and in each one, you seem physically present differently. It’s your chameleon quality, I think. You mentioned you were a gymnast, and as I think about the roles I’ve seen you in, it’s as if you bring a gymnastic intuition or athlete’s versatility into your bodily portrayal of characters.

Thank you.

It’s something that seems to arise viscerally from within; it’s not adopted or put on. Is that anything like how you experience your own role creation?

Yeah. When I get a role I’m not really thinking about the physicality of it—unless, you know, the script explicitly states something, like a limp. But otherwise it all kind of comes when we get up on our feet in the rehearsal room. We’ll talk about the play, I’ll have been doing my homework on it, and then when it’s time to begin working on our feet, I just try to breathe and trust that I’ll adopt the physicality. It’s interesting how that happens. I remember a director telling me, years ago: As long as you remain focused on the trying to get what you want, you won’t have to “play” anything. The character’s traits will just fall on you. I’ve trusted that ever since.

Can I name some plays I’ve seen you in and could I ask you to say a word about your physicalization of your character?

Absolutely.

Your breakout role was Dontrell in Dontrell, Who Kissed the Sea at Theater Alliance in 2015—it was a magnetic performance.

Movement and dance were key storytelling tools in that particular production. The incredible Dane Edidi choreographed that show. Once I was able to get a sense of the movement vocabulary she was putting on our bodies, married with Tim Douglas’s direction, I was able to just play in that framework.

In Darius & Twig at Kennedy Center Family Theater in 2015, you played younger than yourself.

Yeah, he was sixteen, a kid from Harlem, with an alcoholic mother, raising his younger brother and trying to write his way out of his circumstances. Bullied and beat up at school a lot.

Was that easy to find?

A little bit. I know what it’s like to be bullied. I know what it’s like to feel like you’re not enough. I found myself rolling on the outside of my feet for that a lot during the rehearsal process. That trait stuck with me through performances.

Theater Alliance’s Word Becomes Flesh, in 2016 and revived this year, had a poetry in language and a poetry of the body.

Yeah, yeah.

That was also choreographed.

The thing our director Psalm [Psalmayene 24] kept saying was that body language and body politic are a big part of telling the story of Word Becomes Flesh—the history of the black body. We were one of the first productions of that play, so there were no right or wrong answers at all. And Psalm really gave us free reign to create. Again, once I saw the movement that Tony Thomas II, our choreographer, was putting on us, I said, OK well this is the scope that we’re working in so I’m going to play in it. And that was really fun because I was able to go back to a lot of my athletic vocabulary.

In Lobby Hero at 1st Stage in 2016 you played a guard in uniform, and whereas these other parts were lyrical, this one was anything but. I remember thinking, my gosh Justin Weaks is playing burly.

That character takes up some space. He’s a man of authority.

Completely different from what I had seen you do.

I loved doing that play in part because I know that if one reads the script and reads that role, I’m not the first actor you’d think of.

Very counterintuitive casting.

Yeah. But before I even got to the dialogue of the script, the role felt very familiar: William, late twenties, black, Jeff’s supervisor in a high-rise apartment building in Manhattan. So we have a black guy in his late twenties who’s the boss of a man who’s also the same age and white, and he’s the youngest security captain in the history of this company. And that says a lot about this man and what he has to do physically to assert himself in the room. I can’t hide the fact that I’m a small-framed person.

But nobody thought about that watching that performance. In The Christians at Theater J in 2016, you played a preacher man.

I grew up in the church. That was a lot of fun.

Were you channeling preachers you knew?

A bit, yeah. I was playing an associate pastor named Joshua and my youth pastor when I was growing up was named Joshua, so I took a lot of inspiration from him. It was kind of a nostalgic process for me, thinking back to the days when I was in church three days a week.

But it came again from inside, like from a fire in your belly.

That one was very familiar.

The role of Jonelle in Charm at Mosaic in 2017—tell me about how you found Jonelle.

She’s nineteen. Her gender expression is complicated, and the history the playwright gives her is fascinating. There’s an intelligence, a confidence, and a freedom that she moves through the world with that I certainly didn’t have at nineteen. I was like, well I get to just play; I get to really explore the feminine elements of my personality on stage. Getting to know her turned out to be a kind of freeing and liberating experience for me as an actor.

Going from seeing you as William the guard—brusque and burly and totally believable as such—to then seeing you as Jonelle, I thought, my god he just reinvents himself, and he tracks some kind of deep pathway of gender understanding.

I appreciate you saying that. It was a fear of mine when I was coming out of school as an undergrad. I was afraid— I was reading plays and I wasn’t seeing myself in a lot of the work I was reading, and I worried. I said, well a) am I going to work professionally? and b) I don’t want to be boxed in, I don’t want someone to see me as a fresh-faced person and that’s what I’m stuck in. And what’s been so incredible about working in Washington is that here is a community that has been open to seeing me in all these different ways, and I’m really able to stretch my instrument in that way in this town. And I think that’s a rarity. I don’t think actors get that experience a lot.

The most recent play I’ve seen you in is Still Life With Rocket, this year at Theater Alliance, where you played Nathan, the son of an elderly mother. You were skittering all over the stage at the beginning.

That was a young guy too.

And then there was that tender physical relationship between the son and the mother when your character is bathing her.

When you first enter the theater and are introduced to Nathan there’s a sense of imagination and excitement that you see when he’s by himself—then what it’s like when he’s caring for his mother while she’s declining in her mental health.

There’s a segue here to your next play.

Yeah, there is.

You’re now at Studio playing a character named Felix in Curve of Departure. I read the play last night, to prepare for this interview, and I have to confess it had me choked up and tearing. It snuck up on me, then it was like its soul flooded. And the part of Felix even on paper is extremely rich emotionally. There’s a lot going on under his surface. It’s a role that seems to call for a subtler, less physicalized expression.

There was a lot of table-work discussion on this play. We had about five days just talking about the history of these people.

Tell me about Felix’s relationship to the other characters in the play.

Felix is the only character who has a personal relationship with the other three people. There’s his mother, Linda. And there’s his grandfather, Rudy. And his boyfriend, Jackson. Cyrus, Felix’s father, has just died, and Felix has been convinced by his boyfriend that he should go to the funeral. So Felix and Jackson have left their home situation in LA and Felix is really introducing his boyfriend to his mother and father figure essentially for the first time.

What have been some of the challenges in rehearsals?

I’ve never done a play in real time before. This play is done completely in a 60-minute scene and then a 25-minute scene, no intermission. So you see these people’s lives uninterrupted. The time of the story is ever pressing forward. And it’s been a challenge to rehearse the play in chunks, because so much of what’s going on emotionally is directly connected to the moments before.

What’s your favorite moment of the play?

I love the moments between Felix and Linda, the mother-son moments—just really tender, nuanced. Ora Jones, who plays Linda, is a thrill to work with. And the way Rachel [Bonds] has constructed the language, there’s a fluidity to it, and once we start speaking it, it really rolls off the tongue and feels conversational. There are sections of the play that feel very personal, very real.

There’s so much love in the play. And it’s so refreshing to see that Felix’s sexuality is no big deal, it’s like a new normal.

Yes, yes.

Felix’s mother tells him, “You know damn well that I love and accept you, baby.” And later she tells Jackson, Felix’s

I love that scene between Linda and Jackson.

Felix’s and Jackson’s relationship is so sweet and tender.

Yeah, it is. I think it’s a big one for both of them. If Felix has been in relationships before, they’ve been very short-lived.

Felix and Jackson have been together about a year and a half, right?

Yeah. This is his first real relationship. His first love. It’s the same for Jackson.

There are big disclosures in the play, and there’s a very moving conflict between Felix and Jackson that I won’t give away. But it’s never about “Oh-my-god-someone-in-

Not at all.

That’s just not what’s going on. Not for the grandfather. Not for the mother.

She says, “I’ve come so far with you.” There’s some history behind that mother-son relationship with his sexuality. But the play really just accepts these people in this family as they are.

The play made me mindful of the fact that we’re living at a time when this very okay love relationship between two young men can appear completely normal onstage—but if in a sequel they want a wedding cake, the Supreme Court might say a baker can refuse them, or if there’s a film version that opens up to outside, they might get beat up for holding hands. So there’s this world inside the motel room where this play takes place that’s very special and loving.

Yeah.

What are your feelings about the contradictions in this moment that we’re living in, in this country and this city? And how do those feelings connect for you with your sense of who Felix is?

During an early event for donors where the cast talked about the play, a group of Howard students came as well, and one of them asked, “So why this play? Why now?” I think part of it is the family aspect of it. Family can look any way. It’s not defined by how one looks or the blood running through one’s veins; it’s much bigger; family is much more profound than that. And we’re seeing all different types of families in 2017 America. And I always come back to the title of the show. It comes from a poem by Sharon Olds called “First Thanksgiving” that talks about a mother welcoming her daughter home from college during Thanksgiving break. And it talks about what a curve of departure is: When you catch a bee and then release it, there’s a period of disorientation—it curves out to find its way forward. And that curve out is the curve of departure. And I can’t think of a better mirror to hold up to our country right now when it feels like we are in a very intense period of disorientation, and we’re trying to figure out how we move forward out of this. How do we move forward, and how much do we empathize with one another? How much do we give to people we don’t necessarily owe things to? How much of our hearts do we give in the fight for progression and the fight to move forward? And that’s what the play is. The first scene is the disorientation, and the second scene is: How do these people move forward out of this moment and move on with their lives? These four people’s lives have been moving like a fast freight train, and then Cyrus’s death happens, which causes them to be in this room and deal with what’s been happening out there in a way that they wouldn’t have been able to do, because: Life, it happens so rapidly and it rolls. In a way, that death gave them a gift.

One last question. Your bio says “The Revolutionary Theatre” by Amiri Baraka changed you. How so?

I came across that essay in college, in a time when I was very conflicted about what my role would be as an artist in the theater. I was trying to find my footing about what it meant to be a black queer man in the theater and what stories I can tell. That occupied a lot of my thoughts as a younger person—also about what theater meant to me, what acting meant to me, what I wanted in life, what I wanted in art. And I read that essay, and it really opened me up to what my responsibility is as an artist and what my job is— to crack my soul open, for other people to see theirs.

Running Time: About 80 minutes, with no interission.

Curve of Departure plays through January 7, 2018, at The Studio Theatre – 1501 14th Street, NW, in Washington, DC. For tickets call the box office at (202) 332-3300, or purchase them online.