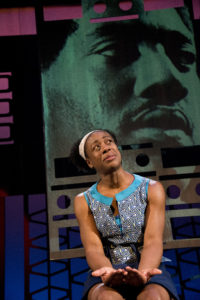

Erika Rose’s performance in Queens Girl in Africa is awesome to behold. She plays the playwright’s teenage self, named Jackie, plus her parents, school friends, and others, with an incandescence that won’t stop. The coming-of-age story tells of the time in the 1960s she and her family lived in Nigeria. It picks up the storyline that began in the playwright’s Queens Girl in the World, which took place in New York City and was performed three years ago by Dawn Ursula.

The first Queens Girl play was commissioned for the first Women’s Voices Theater Festival by Ari Roth when he was artistic director of Theater J. Now artistic director of Mosaic Theater Company, Roth commissioned the second Queens Girl play for the second Women’s Voices Theater Festival. So externally the plays are of a piece, but within them is an even deeper connection.

Between my memory of seeing Ursula as Jackie and now seeing Rose as Jackie, it was as though I had witnessed a continuous self, or a transmogrification of the same soul, first in one exquisite embodiment then in another.

Though Queens Girl in the World and Queens Girl in Africa each stand alone, taken together they are a beautifully theatricalized bildungsroman, a sweeping moral memoir of “How I came to know who I am” that makes the audience want to know Jackie too. Which is also to want to know the voice of the author.

The life depicted onstage in the Queens Girl cycle was adapted by Caleen Sinnette Jennings from her own. Jennings, a professor of theater at American University, was a member of the original Welders, which produced her Not Enuf Lifetimes, a play I admired enormously. When I asked if I could interview her to know more about her writing of the Queens Girl plays, she generously agreed.

John: The storytelling in the Queens Girl cycle is personal and political at the same time. How are the two plays connected for you?

Caleen: When I wrote Queens Girl in the World, I considered that my one semi-autobiographical play. I had made up my mind I was not going to write anything like that again.

Fortunately for us you changed your mind.

It was Ari who convinced me. I told him, I said no I’m really not interested. And he took me to breakfast, so be careful if he invites you to breakfast.

They say life is lived forward and understood looking backwards. That kind of looking back is very emotional, and I had never written anything like this before, so I had a tremendous amount to learn. Just going from narrative to dramatic writing was difficult. There are characters that I conflated and things that I omitted and that were cut for time’s sake.

One of the things I always tell my playwriting students is: Don’t write anything autobiographical, because as you’re living your life, life happens to you, but in the theater, you have to have a protagonist that’s active and that does things. And really you’re not aware of what you’re doing when you’re living your life. You’re just having things happen to you and you sort of respond. So with Queens Girl in Africa, looking back and trying to answer the question that Ari, the director [Paige Hernandez], the dramaturg [Faedra Chatard Carpenter], and the actor [Erika Rose] kept asking me—But what did YOU DO?—was difficult and intense and interesting.

The thing Ari said that convinced me to write Queens Girl in Africa was: You’ve learned so much in the first process. Give yourself a chance to apply what you’ve learned a second time. And that’s really what happened.

I certainly did not feel wise at the time. If you had spoken to me in fall of 1968, I was still worrying about: my canines are crooked and my feet are too big. So in writing the play, it was tricky to balance and frame artistically what you now understand about what you were going through and experiencing at the time. I couldn’t have articulated any of this to you then, but I understand it now.

All the teenage angst-y things about boyfriends and crushes and such is delightful, and both Dawn and Erika were wonderful playing that teenage self. And what for me was so rare is that the plays dramatize something very elusive, which is self-knowledge about oneself in the world politically. It was a continuous coming-of-age, coming-to-race-consciousness narrative, as I saw it. And I’ve never seen first-person theatrical storytelling quite so clearly frame a life in terms of the social-political landscape.

Well, you know, my parents and my grandparents had a lot to do with my sense of self. Ours was a house where we read and debated and watched television and talked about it. I went to Elizabeth Irwin High School, where we read The New York Times in class and talked about what was in the news, and we were assigned community service that we had to do, so we were encouraged to think of ourselves as citizens who had responsibility.

I got the sense there were playwriting lessons that you built into both works and we might not be aware of them, but the playwriting teacher in you was leaving behind gems of information, and if anyone was going to write a story about themselves with as much political perspicacity as you’ve shown, these are the things to keep in mind.

Well, any playwriting lessons in the play were not conscious because I was struggling to learn how to write it as I wrote it. So I don’t feel as if I left any hints or tips. Luckily I had an amazing dramaturg, Faedra, and Paige and Ari who encouraged me and helped me shape the piece. I give great props to them. My original script was 150 some pages, and we cut it to around 60.

In the first part, Jackie talks about writing as helping her “make peace between the Erickson Street Jackie and the Irwin School Jackie”—meaning who she is in the mostly black Queens neighborhood where she lives and who she is in the mostly white elementary school she goes to in Greenwich Village. Then in part two she goes with her parents to live in Nigeria and asks “Am I afraid of Africa? … Who will Africa Jackie be?” And there’s this shocking moment when she realizes that she—as an American not born in Africa—is being called a word that means “white foreigner.”

Yeah.

My heart just sank. And in that moment I saw this powerful arc you had created about who Jackie conceives herself to be and who she’s perceived as: which Jackie is she? It was the kind of storytelling that keeps you completely absorbed but also, if you step away, it stands out as emblematic: like, everyone should be able to have that kind of self-awareness of who one is and who one is in context. It became more than storytelling; it became a parable that we could all learn from.

Well, you know, every teenager thinks something’s wrong with them, every teenager thinks: I don’t fit in because something is wrong with me, or: there are so many aspects of my personality, I’m not even sure which one is the real me. So if there’s one thing I would like people to take away with them it’s the moment Jackie discovers when she’s doing theater: Oh, my gosh, I can be three different Jackies in one body!

I went through adolescence decades before we had the term code-switching. So at the time I just thought I was crazy. But everybody has to adapt depending on where they are, what they’re doing. And that was a revelation to me. So I hope one of the things people will take away is: no, you’re not crazy; you’re adapting to circumstances, many times circumstances that are very difficult, but it’s all part of who you are. Claim all of your multiple selves.

One of the things that sets the Queens Girl plays apart from other coming-of-age stories is that the drama of Jackie’s self-understanding and emergence isn’t just about intra-family dynamics. There are historical events that crash into the storyline: the Baptist church bombing in Birmingham and the assassination of Malcolm X in part one; and in part two, the assassination of Dr. King, the race riots in America, and simultaneously the tribal war in Nigeria. At one point Jackie realizes, “The tribes don’t like each other.” I found that historical contexting of Jackie’s personal-growth narrative powerful: like a lesson for all.

I always tell my students: tell your story with as much detail as possible, because the thing that you don’t expect other people to understand—and the things you think: this will be boring, nobody will get this—are sometimes the things that really resonate with people. If you had asked me a month ago: are people going to respond to these things? I would have said: I absolutely have no idea.

Most people don’t think of themselves as being impacted by historical events the way Jackie so clearly does. That’s what’s so beautiful about her story: it shows us how events in the world become part of us.

I think that was also the flavor of the times. As boomers in the sixties, we were told we were special and we were going to change the world. Also: Don’t trust anybody over 30. One of things that sometimes makes me sad is that students I teach often don’t have that sense of empowerment; they’re too worried about finances, they’re wrestling with health issues, they’re worried about their families who are paying for their education, they’re worried about things like insurance. I didn’t even know what insurance was when I was 18. I had time to be an idealistic wannabe activist.

There’s another level of the plays, which is as a parable of exemplary parenting. Your parents saw a matinee of Queens Girl in Africa the day before it opened, and you were there in a talkback with them. What was their reaction?

Well, I got a little emotional at one point during the post-show discussion, because somebody asked me: How does it feel to have your parents here? And I said: I hope this will be a tribute to the gift they gave me. They enabled me at age 18 to see myself as a citizen of the world. [Jackie’s mother] Grace keeps saying to Jackie: You’re strong, you are smart. When I look at the kinds of things they taught me, I’m so grateful. My parents are Depression-era babies. So a lot of what you see in the two parents in the play is a reflection of their upbringing. They’re 93 and 92 now. They came and were very appreciative. And wow, it was amazing.

Near the end of Queens Girl in Africa, Jackie gets accepted into Bennington, which at that time was a very interesting place to be political. Will we find out what happens to Jackie there?

I’m resisting, but Ari announced to the audience that he’s taking me to breakfast.

Lastly, I want to ask you something from your perspective and stature in the theater and the community as an esteemed elder—which I take to be a mark of honor and I hope it fits you that way too.

I fear that’s a little hyperbolic, John. But it warms my heart to hear you say that.

Well, I think a lot of people think of you that way, and I know some of them because I’ve met some of your students. And I can also sense the wisdom that suffuses the work of yours I’ve seen. So my question is: From that perspective, what do you see as the biggest challenges regarding representation in DC theater of the voices of women and people of color? And what would you like to see happen that hasn’t yet?

Well, I think important things are happening. To go to the theater and see [my former student] Jonelle [Walker]’s play [TAME.] last year was just so incredibly exciting for me. We represent such a wonderful span of ages—from boomers, to millennials, to gen-x—and I see these young folks writing their own plays and forming their own companies and speaking out about how things need to change.

They have these questions: why do things have to be like this? what if we did this? what if we did that?

DC embraced us Welders. In any other city it could have been: well, who do they think they are? And the established theaters could have said: well, let ’em go off and try; see how far they get without us. Instead, it was a full-on embrace and cheerleading that was unbelievable. And now to see Welders 2.0 come into its own, I think I see more movement than obstacles.

I see an understanding of the fact that individual artists have to take more responsibility, and theater establishments when they open up and embrace the agency of young artists will only continue to grow, and audiences will reflect the generational differences. I think everybody is coming to the realization there are certain things that have to be done to make theater continue to be relevant. There are some really smart people here. And I think DC is way out front in terms of doing some of those things.

Women’s Voices Theater Festival happened way before #MeToo. We’ve got all these fabulous universities. We have the Fringe Festival. We have Kennedy Center Page-to-Stage. DC is really an ideal place to examine what the key issues are and what people are doing to solve them, to get out ahead of some of the obstacles in the way of theater professionals.

It is a very exciting place to be at this very exciting time.

It is. I know of very few places where people would say: Yay, a new play that’s never been done; let me go and see a preview before it’s reviewed, on the coldest day of the year. It was astonishing to have 130 people come to a preview of Queens Girl in Africa on a night that was absolutely frigid for a play that nobody had any guarantee would be any good at all. And people came and wanted to talk. That’s pretty special.

Running Time: 100 minutes including a 15-minute intermission

Queens Girl in Africa runs through Sunday, February 4, 2018, at the Atlas Performing Arts Center, Lang Theatre – 1333 H St NE, Washington, DC 20002. For tickets, call the box office at (202) 399-7993 ext 2 or purchase them online.

WVTF Playwright Spotlight: Caleen Sinnette Jennings

Caleen Sinnette Jennings is Professor of Theatre at American University in Washington, DC. She received the Heideman Award from Actor’s Theatre of Louisville for her play Classyass, which was produced at the 2002 Humana Festival and has been published in five anthologies. She is a two-time Helen Hayes Award nominee for Outstanding New Play. In 2003 she won the award for Outstanding Teaching of Playwriting from the Play Writing Forum of the Association of Theatre in Higher Education. In 1999 she received a $10,000 grant from the Kennedy Center’s Fund for New American Plays for her play Inns & Outs. Her play Playing Juliet/Casting Othello was produced at the Folger Shakespeare Theatre in 1998. In 2012, Ms. Jennings’ play Hair, Nails & Dress, was produced by Uprooted Theatre Company of Milwaukee and by the DC Black Theatre Festival. Her most recent publication is Uncovered, in the 2011 Eric Lane and Nina Shengold anthology Shorter, Faster, Funnier. Dramatic Publishing Company has published: Chem Mystery, Elsewhere in Elsinore: the Unseen Women of Hamlet, Inns & Outs, Playing Juliet/Casting Othello, Sunday Dinner, A Lunch Line, and Same But Different. Ms. Jennings is also an actor and director. She received her BA in drama from Bennington College and her MFA in Acting from the NYU Tisch School of the Arts.