As parts of the nation settled in to hear 45 read the script of the State of the Union address, and other parts assiduously ignored the same, balletomanes and ballet goers in the Washington area welcomed a program of new and recent choreography from American Ballet Theatre (ABT) to kick off its annual Kennedy Center Opera House season. I’ll leave comments on the SOTU to the political pundits, but can proclaim wholeheartedly that, on the heels of a tough year for ballet companies, from shrinking budgets, to rising touring costs, tighter visa restrictions for foreign artists, and year-end revelations of sexual harassment and abuse in companies large and small, the state of ABT is strong. In fact, I haven’t seen the company as a whole dance this well since its heyday in the mid-1980s, when premier danseur Mikhail Baryshnikov served as artistic director.

Tuesday evening’s program of four works – three by living male choreographers created in the past decade – showcased the company’s commitment to building repertory for the 21st century, instead of recycling the tried and true of the past. Though none were world premieres, these offerings demonstrated a high level of sophistication that demanded far more from the typical “story ballet” crowd that fills the Opera House on Saturday nights and weekend matinees for the “Swan Lakes,” “Giselles” and “Le Corsaires” that the company can churn out.

Artist-in-residence Alexei Ratmansky has been a prolific dancemaker, creating pieces for his current home company, ABT, as well as for New York City Ballet, the Bolshoi Ballet in Moscow, which he directed from 2004-2008, and many others. His choreography demonstrates an astute awareness of the classical underpinnings that remain integral to the art form, but he has a fresh take on how these classic steps get put together and, more essential, how dancers perform them. “Serenade after Plato’s Symposium” shows that he’s in top form, creatively, intellectually and technically. The work is among his best, featuring seven of the company’s male principals in unexpected and consequential solos that focus on new their distinctive personalities and putting them far enough outside their comfort zone to allow them to shine.

Ratmansky takes self-assured inspiration from a less-well-known, but by no means lesser, score from Leonard Bernstein. “Serenade after Plato’s Symposium” is a violin concerto (here marvelously played by Kobi Malkin), joined by strings and percussion, especially deep timpani. The composer crafted it in 1954 after a Platonic dialogue and you can hear the questions and answers in the score, as well as the distinctive voices of the participants. Ratmansky follows both the intellectual tenets and the emotional currents Bernstein put into play, placing his dancers in conversation, giving them singular solos – danced monologues – and drawing them together into a larger discursive group, Platonic discourse embodied.

The work for seven men is filled with smartly executed Ratmansky-isms – complicated but pure bits of footwork that showcase the swiftness of feet and legs in a fashion not often seen in new ballets that too often focus on hyperextensions, and gymnastic-like tricks or other elements peripheral to the choreography. But Ratmansky loves and honors the ballet dictionary, the vocabulary that dates back to the French court. The more complicated and honed the footwork is, the more interesting it makes the choreography. And the more interesting the choreography, the better the opportunities dancers have to step up to the plate and hit it out of the park. Atop this evolving base of old and new, he allows for a sense of open expressiveness in the upper body, emphasizing epaulement – the shifting placement of the shoulders and head to enliven and add dimension to the dancers’ interpretations. For this “Serenade,” they really use everyday conversational hand gestures – widespread and open arms with palms up, a questioning shrug, an emphatic fist, an accusatory forefinger – which are more than decorative, they’re essential to the work’s development and purpose.

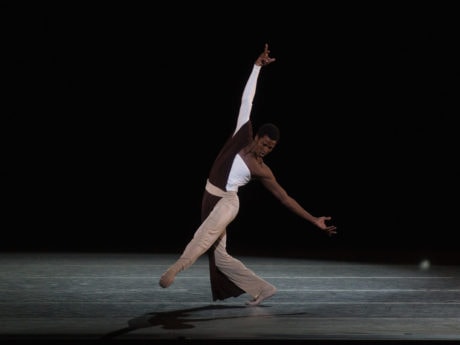

Most striking in “Serenade” is the luscious attention to detail from the dancers, from soft-footed landings following soaring jumps, to gentle bourrees – a quick gliding step most often associated with women dancing en pointe – to sequences of freshly executed pirouettes, full body reverses, and a simple repose. Here Ratmansky gives his men equal opportunity to showcase their softer, feminine sides in choreography that allows for a different dynamic and level of attack than is typically expected of male ballet dancers. The men are draped and swathed interestingly in muted tones of gray, beige, rust, black and crisp white, the varied costumes by Jerome Kaplan suggesting the one-shouldered classic Greek toga. Brad Fields’ lighting, too, assists in distilling each of the seven singular performances, and also adding special effect upon introducing the one woman in the cast.

This “Serenade” is a men’s dance: by, about and for men. But it’s also a dance about Love – not cupids and cute Valentine hearts and happily ever afters. This is Platonic love, a divine inspirational connection to the idea of Eros, a transcendent, non-sexual love that rises above the banality of happy endings. Bernstein’s inspiration was the Platonic symposium – an intellectual conversation where the ultimate truth and beauty are in service of Eros.

Interestingly, Ratmansky has avoided any homoerotic undertones in his danced “Symposium” – instead providing heartfelt camaraderie, friendly sparring, frustration, joviality, even disruption. It’s an idyllic universe of music, dance and ideas. They cuff one another like playful lions, but they also question, shrug, clasp hands, brush off and draw in their compatriots as Ratmansky pulls from non-verbal gestures that allow an easygoing verisimilitude. As shifting configurations of twos, threes, fours and the entire group evolve, some dancers peel away to recline, Greek style or to sit on the sidelines regarding their brothers in debate. There’s a real-world feeling to this conversation – or symposium – and the oversized tilted placard states in Greek letters just that, “symposium” at the start of the ballet. By the end it is upturned and becomes a cloud or canopy, hanging above the dance space.

On opening night, Jeffrey Cirio’s solo set the conversation in motion, Calvin Royal’s lush adagio — in his split personality half black, half white costume – let him stretch to his fantastic height. Gabe Stone Shayer seemingly invented new jumps and skips and leaps from thin air in an airborne section while littler Daniil Simkin was playful in his lightness and larger Alexandre Hammoudi seemed stoic. Blaine Hoven, in his white jacket, appears to lead, while bearded James Whiteside played up some of the more feminine steps — crossed Romantic-style wrists, bourrees — with tongue in cheek.

Then, like a deus ex machina, Eros appears in person, entering through a gold-lit opening in the back curtain. Eros (Devon Teuscher in a pale blue dress) dances a brief, entangled duet with before exiting, and this is, interestingly, the least compelling part of the work. The pas de deux is ordinary, while the men’s previous solos and duets were extraordinary, filled with sentiment, moments of softness and rigor.

This was the program’s gem, a keeper that should be well on its way to masterpiece status.

Alas, the revival of Jerome Robbins’ small but not inconsequential pas de deux “Other Dances,” originally made for the incomparable Mikhail Baryshnikov and Natalia Makarova in 1976, provided an example of what happens when a dance is mothballed and remounted without care to casting and attention to detail beyond the steps. Isabella Boylston and Cory Stearns managed the technical demands of Robbins’ highly evocative choreography without a glitch. They simply had no passion, either for one another, or for the poignant yet lilting Chopin pieces that suggest a lost Russian world of mazurkas, booted men, and aproned women, borscht and dachas in the woods, which the choreography acknowledges in the snappy heel closes, hands resting proudly on waists; toe and heel taps, and even – here, entirely too timid – an emphatic floor slap. Alas, neither dancer projected that soulful longing for each other or for bygone days. “Other Dances” evokes another time and place, when wearing one’s heart on one’s sleeve added life and zest to the piece. The Chopin was lovingly played on piano by Emily Wong.

Christopher Wheeldon’s “Thirteen Diversions” is a small piece, a collection of duets, made bigger by adding a 16-member corps behind the four solo couples. Wheeldon’s most memorable dance moments for me have been his duets – here he multiplied those by spreading paired couples across the stage as decorative ornamentation and filtering them in clumps. Danced to Benjamin Britten’s “Diversions for Piano and Orchestra, Op. 21,” the 13 variations melded into one another, while Fields’ lighting, opening with a triangular corner of the backdrop glowing and growing, before evolving into changing colors and temperatures as a bar of bright orange, then blue, then purple, bisected the wall horizontally.

French-American choreographer, former short-lived director of the Paris Opera Ballet, Benjamin Millepied dabbled in post-modernism with some outtakes from Philip Glass’s “Einstein on the Beach.” On a stage stripped of scrim, drops and all accoutrements, the dancers march across in a platoon, before the lights come down. Clad in gray tanks and black biker shorts from the rag and bone catalog, the dancers look small and inconsequential in Millepied’s pastiche of exercises and floor patterns for the large cast. Even megastars Misty Copeland and David Hallberg – recently back after a long recovery from an ankle injury – needed something more substantial to shine.

Intentionally the piece felt regimented, with much walking and dancing in unison, canon, and succession and much that likely required a traffic cop to keep order as lines crossed and bled in and out of one another. In the opening section, “Tremor,” Copeland pulls and prods Hallberg from the floor, they push palms against each other and each has a moment before the group overtakes them. Throughout there’s a push against the solo and partnered dancing as the group usurps the individual or couple. At times their mouths covered by black kerchiefs, it’s hard not to think of rioters or protesters, yet the work felt bland, not statement-making.

Much has been written about Millepied (spouse of Hollywood’s Natalie Portman) challenging ballet with something fresh and shocking. But these ideas, themes and barebones staging have a long history in modern dance. Perhaps some ballet audiences may experience shock and awe at the discomfiting usurpation of classical modalities and techniques, but it can’t possibly be that many. In the larger dance world this is rather ordinary. As lovely as it was to see Copeland and Hallberg, along with fellow principals Herman Cornejo, Hee Seo, Stearns and Teuscher, they weren’t able to shine in this dreary piece. It was hard not to wish for another Ratmansky work on this program, which began so promisingly.

Running Time: Two hours and 30 minutes, with two intermissions.

American Ballet Theatre: Ratmansky, Robbins, Millepied & Wheeldon played through January 31, 2018, at The Kennedy Center’s Opera House – 2700 F Street, NW, in Washington, DC. American Ballet Theatre: Whipped Cream plays February 1-3, 2018. For tickets, call the box office at (202) 467-4600, or toll-free at (800) 444-1324, or purchase them online.

My reactions to the Tuesday performance was identical to yours.

I also got to see the Wednesday night performance and would like to add that Other Dances with Sarah Lane and Herman Cornejo was pure ballet heaven with all the missing qualities you noted in your review.

Glad to hear it, lholxs. I was at Grupo Corpo’s performance on Wednesday, so, alas, missed Lane and Cornejo.

And I’m just going to leave this here: Baryshnikov and Markarov in “Other Dances.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dKYUAp9nxmc

I enjoyed your review very much although I didn’t see the performance. The youtube clip you left is one I’ve watched … hundreds of times! It’s the gold standard.

Opened in Chicago last night with Hee Seo and David Hallberg in Other Dances. It was completely lackluster as you described and void of passion. The onstage pianist I felt didn’t project, either for some reason. It was all so surprising. I look to the 1978 Gelsey Kirkland/ Baryshnikov version as the most beautiful thing I’ve ever seen.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4ApkdFh3VPQ

An excellent review. This was exciting, sexy, engaging, and thoughtfully education. Brava and thank you.