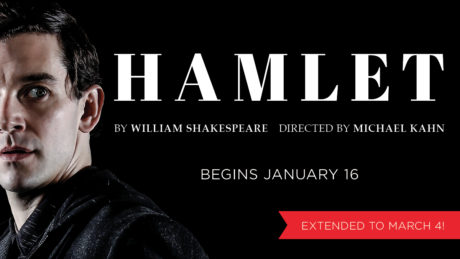

When I had a chance to ask Michael Urie some questions about his performance as Hamlet, I learned he can hold forth as insightfully as the character he plays. Well, maybe minus the verse and plot. But still, for anyone who has seen Urie in the production Michael Kahn directed at Shakespeare Theatre Company—or for anyone in the future curious about this uber-talented actor’s take on the role—what follows will fascinate.

And if you haven’t seen Urie’s Hamlet yet, hurry. The show closes March 4.

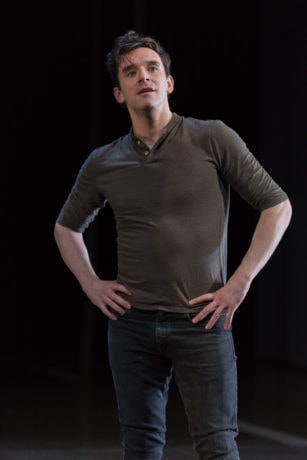

John: I found your performance thrilling, and what has stayed with me most about it is your unselfconscious expressivity, the virtuoso fluidity of your voice and your physicality. It really felt liberating to watch.

Michael: Well, thank you. I’ve heard versions of that. One of my favorite comments was somebody who was way up in the balcony, because as you know, that’s an enormous theater. And somebody up in the balcony said to me that they really enjoyed the physicality of the performance, and that I must have been a dancer. And I get that a lot. People often think that I’m a dancer. I’m not, at all.

But I take it as a great compliment because I think that physicality on stage, especially in a big theater, is important. On screen, TV, or film, you tell a story with your eyes and your words and your face. And on stage, if you have a big face like I do, you can use your face. But not everybody can see your face. It has to be done with your voice and your body. And so, to hear from somebody up in the balcony that they were getting some story from me physically is very gratifying. Because I think about them up there all the time. I think, My gosh, they’re so far away. I hope they’re getting this.

In this production, the play starts with a soliloquy of Hamlet’s. The guard scene with the ghost of Hamlet’s father comes later. It’s like a cold open. I thought that was dramatically brilliant, and it meant your performance had me at hello. But there’s no onstage action yet that you might use to motivate you. What’s going on for you before the play begins? Are you picturing events that have affected Hamlet’s state of mind?

Yeah, I imagine that this is me, Hamlet, shortly after the wedding of my mother and my uncle, and I just don’t know what to make of it. I’ve been at school. I’ve been told my father’s dead, and that my uncle’s going to be king, and I come home. I don’t really care that I’ve been passed up for king. That’s not really ever been anything, and I’m so shocked that my father’s dead, and so upset that my father’s dead. And the text supports that he doesn’t really have ambition to be king.

It isn’t until later in the play that you get a sense that he regrets not being king, and he wishes he was. Or, that he should have been, and that perhaps he’s done Denmark a disservice by not being king. And so I think at the beginning, he’s so sad that his father is dead, and then so angry that his mother married his uncle, who he hates. And he has no one to talk to.

He loved his father. He loved his mother. But now, he doesn’t understand either of them. And so he turns to the audience. Obviously, it’s not actually the audience, but in the world of a play, and certainly in the world of Shakespeare, characters do turn to the audience to share their inner thoughts.

And I agree: Michael Kahn’s idea to put that speech at the beginning was totally brilliant. Because usually you sit through the entire first ghost scene and the entire first Claudius scene, which in our production is a press conference, and then you find out what Hamlet’s so upset about. And you’ve heard about what’s going on, over and over again. The king is dead. The queen is still the queen, and the uncle’s now the king and all this stuff. You’ve heard about it, but you don’t get Hamlet’s point of view until the very end of that second scene.

And to put it front and center not only gives Hamlet license to not have to just brood all the time. You can know what’s wrong with him, and then see how he behaves publicly. Because of course, in Shakespeare, it really is all about public versus private. When there are soliloquies on the side, you get the private thoughts. That’s them being private and being personal. And then, they are often different publicly.

And a problem I’ve always found with Hamlet is that poor Hamlet can’t really be that until you find out what his problem is at the end of the second scene. Until Claudius’s big speech in Act 3—“Oh, my offense is rank. It smells to heaven”—Claudius doesn’t say anything bad. He’s concerned about Hamlet, but you don’t know why he’s concerned about him. And so, if you hear from me right away, I hate that guy, it gives the actor playing Claudius license to be charming and good and likable.

Michael Kahn has said he would not have done Hamlet if he couldn’t get you to play it, which I totally get, having seen the production. Why do you think it was your Hamlet that he wanted to build that production around?

Gosh, I don’t know. I know that when I did Buyer & Cellar, that one-man comedy about Barbara Streisand that I was in for a long time—

I saw it and loved it.

You did? Did you see it here?

Yeah.

Okay, so I think it was when Michael saw me do that play that he first had the idea, because a lot of that play was direct address. And I think he saw me in the Harman talking to the audience, and he thought, “Oh, that’s like Hamlet. Maybe he could play Hamlet.”

And then he saw me in another play called Homos, Or Everyone in America by Jordan Seavey, at the LAByrinth Theater in the West Village, which was about the ups and downs of a relationship between a writer and an academic, and I played the writer. And the character was very dextrous with language. It wasn’t a heightened language. It was actually very modern, but it was very technical. It was a lot of overlapping and a lot of talking at the same time or finishing each other’s sentences. It was a wonderful play, and it was actually in the lobby after Michael saw it that he asked me to play Hamlet.

And that play was funny, and it was cruel, and it was tragic. It had a lot of the elements that Hamlet has. So I guess when he asked me to do it, and as I prepared to start working with him, I thought, Okay. What is it about those two plays, which are wildly different, that make him think of Hamlet, and how do I attack our Hamlet with that in mind?

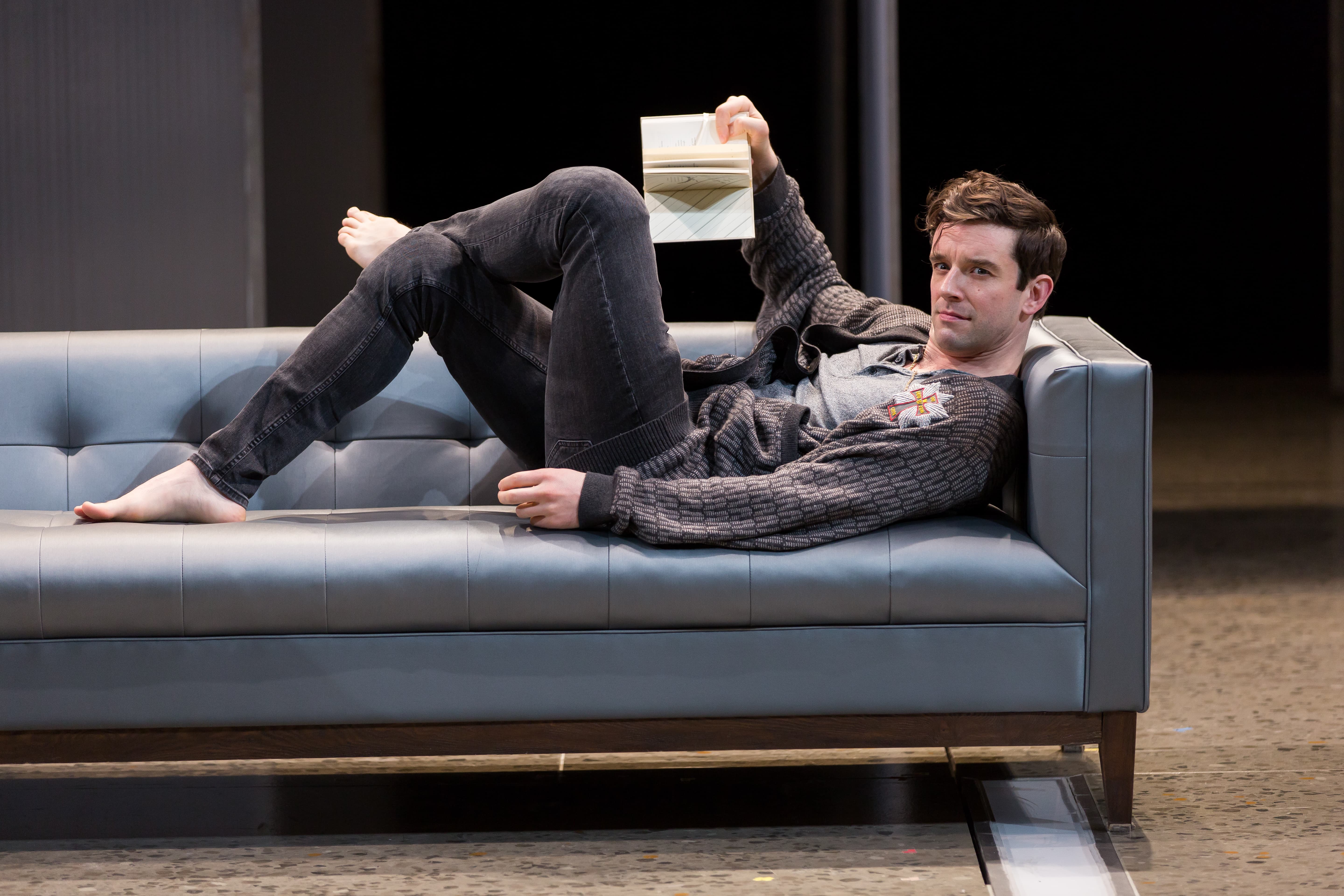

One of the things that struck me about your performance is that although textually the character is often taken to be inscrutable, you made Hamlet in person seem completely accessible and relatable, like a fresh start for experiencing the character.

Well, thank you, that’s an interesting observation. And I would say that that comes from the text. I know that Hamlet is often thought of as brooding and mysterious, but actually, you know, they call him sweet lord, sweet prince, sweet Hamlet. I actually think that the Hamlet that we don’t meet, that everyone has known, is a sweet guy. He’s sweet. They say sweet, and I think it means the same thing now that it did then. I’m sure it means other things too, but I think that he was a likable, kind, thoughtful person.

He has friends. They say that he’s liked by the people. His mother lives by his looks. And at the beginning of the play they say, Why are you still so sad about your father’s death? I think that there’s a change in him, and that the real guy is an accessible, charming guy who likes to talk to people and who is interested in argument. You know, he’s the kind of guy who will wander through a cemetery and go strike up a conversation with the grave digger. I think that’s Hamlet, and the fact that he is shrouded in black at the beginning of the play, and he is depressed, is what’s different.

That’s not the guy. That’s not Hamlet. He has become that because he’s so upset at the beginning of the play. So to me, the guy we meet at the beginning of the play is not the guy he’s been his whole life. And so that gives us license to fall into the other guy. He loves Horatio. That’s his friend from school, the guy he loves to talk about philosophy with. And then when Rosenkrantz and Guildenstern come in, he can fall into this old camaraderie that he had with these two where they would play with words. And then of course, he realizes: Oh, I can’t trust these two.

And the same thing when the players show up. He loves the players. He loves watching plays. And when the players show up, it is genuine. So it is not always through this mask of: he’s a depressed, brooding, moody guy. The depression and the angst is new. So that’s why I think Hamlet is able to go from the nunnery scene, where he’s filled with rage and violent with Ophelia, into the speech to the players, within a matter of lines, where he’s silly and funny and charming.

And I think Shakespeare is telling us, This is who this guy is; he goes from thing to thing.

There was an ebullience in your performance as I saw it, and as I was interpreting what you were doing. Your performance is faithful to Hamlet’s antic disposition, but it also seems very true to a contemporary sense of personal freedom—in particular, freedom from those vocal and behavioral constraints by which masculinity is supposed to be performed. It’s like you’re portraying a freedom from the mask of manhood. And by the way, I’m not talking about whether Hamlet is being played gay, because you can be gay and stuck inside that mask. I’m talking about this other particular quality in your performance that so riveted me. It’s what I called earlier your unselfconscious expressivity and your virtuoso fluidity of the voice and the body. I think it’s something that profoundly illuminates the character and the play. Are you okay if we go there?

Sure, yeah. Sure, sure, sure. It’s an interesting idea.

After I saw your performance I got to thinking: If Denmark is a prison, so then, by extension, are these conventions of stereotypically dominant masculinity, which are represented in this production by all the cold gray ambiance, police state trappings, the Nazi-like imagery that shows up late in the play. By contrast, your Hamlet is an anomaly. In the script, he no longer fits in, he can’t and he won’t. But your performance makes that outsider status a form of resistance to and escape from the prison. It’s called hegemonic masculinity by academics, but you know what I’m talking about. You can disagree if you like. It won’t hurt my feelings.

Oh, I don’t. Claudius says, in his first scene with Hamlet when they’re trying to cheer Hamlet up and tell him to cast off his nighted color, he says basically: Of course, everyone loses their father; everyone’s father dies. And Claudius says, “But to persever in this obstinate condolement is a course of impious stubbornness. ’Tis unmanly grief.”

Ah.

Yeah. And I think that that is absolutely there.

You know, it’s debatable how old Hamlet is. But he’s definitely not college age anymore. If Yorick died three and 20 years ago, which is what the gravedigger says, and Hamlet remembers him, then he has to be at least, what, 26, 27? So I think he is some kind of perpetual student. He’s still in school. He’s not following in his father’s footsteps or he would be king. He would not have left Denmark. He would have stayed in Elsinore, and he would have been his father’s right-hand man. And I think because he loved his father, I think that his father supported this decision, and he said, Yes, go. Study philosophy. Go be a student. Go live your life. Go have fun. Go be yourself. And I think that Hamlet has been allowed to be himself.

And now, because he’s been absent, his uncle’s been able to usurp the throne. And so I do think that Hamlet has followed his own heart. And it is poetry, and it is theater, and it is philosophy, and even maybe religion. I think he’s a religious person too. But it’s not politics. It is not war. He has not regimented himself. He lived his life. He hasn’t been focused on the future of Denmark, or his political career or power. That’s what his uncle’s been trying to get. And here are all these buttoned-up guys in suits and security. And I think that he leaves Denmark because it’s boring. He doesn’t like it. I think that the Denmark he returns to is the prison.

Hamlet’s mother seems to really love Ophelia, and seems to really want for Hamlet and Ophelia to have been together. But nobody else does. And that is a forbidden love. Hamlet and Ophelia obviously care for each other very much. Whether or not it’s true love, whether or not he wanted to make Ophelia his queen, doesn’t seem to be interesting to Hamlet, and Hamlet doesn’t want to be king. And he doesn’t stay. He stays perhaps partially because of Ophelia. I think he sees Ophelia as someone that he can speak to, trust, until he can’t anymore, which is heartbreaking to him. But he’s not allowed to be with Ophelia in Denmark, so he has to go someplace else and follow his heart elsewhere.

Your Hamlet seemed to me someone who has not outgrown the emotional volatility of adolescence. I sensed a very contemporary sense of what that means: Feelings erupt, feelings do switcheroos. Plus, he’s not trapped inside heteronormative armor. So his soliloquies become a kind of emotional sharing that feels generationally very true. Does that sound to you like what you’re doing?

Yes, I think so. He’s still a student, and he is still eager to learn—all the things that come with being a student and being surrounded by different kinds of people, and being immersed in other cultures and other ideals. He says, “There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy.” I think that they spend their days arguing. They probably get high and argue about life and politics and religion, and all those things that students argue about.

And I think that because Hamlet is rich and privileged, he’s never had to do anything but that. And so I really think that that’s why he is so struck by all of this, because he’s not had to grow up yet. And he is forced to grow up by the actions of this play. And it ends up with him having to murder somebody, and I think going crazy. He of course pretends to be crazy. Like when the ghost says to him, “Taint not thy mind,” meaning: Don’t let yourself go crazy while you’re doing this. While you’re figuring out how to avenge my death, don’t lose your mind.

And immediately after Hamlet sees the ghost, he says to Horatio and Marcellus, Guys, I might pretend to be crazy. Don’t tell them I’m pretending. And then he overhears Polonius and his uncle and mother talking about how he’s gone mad, before he’s even had a chance to put this antic disposition on, really. They say, He came to Ophelia’s room and he was crazy. And to me, he came to Ophelia’s room right after he saw a ghost because where else is he gonna go? And he couldn’t tell her about the ghost. He couldn’t do that. He loves Ophelia. He couldn’t put her in that kind of danger. He couldn’t say, I saw my father’s ghost. Because that would not only put her in the middle of it all but she would have to go and tell somebody, Oh, my gosh, what’s going on with Hamlet? And indeed she does. She goes and says to her father, “I’ve been so afrighted. My lord, I’ve been so afrighted.” And Polonius says, Ah, this is why Hamlet is different. We’ve all been wondering why is Hamlet so different. And the mother’s like: I think it’s obvious. He’s upset about his father dying, and he’s upset about me getting married so quickly.

And they’re like: No, no, no, no; it can’t be that. It must be that he’s in love with Ophelia. And of course it’s not that. It’s what his mother said, and it’s what the ghost said. So in our production, Hamlet overhears this whole conversation. He overhears Polonius go to his uncle and mother and say, He’s mad for Ophelia’s love, and so this is how we can try it further. This is how we can prove it. We will get Ophelia to spy on him for us. And so in our production, brilliantly, I think, Michael Kahn has Hamlet overhear that.

And so then the antic disposition that he ends up putting on, that he says he’ll put on, is only to further the idea that Polonius and Claudius and Gertrude have, that it’s all about Ophelia. So in the fishmonger scene, when he’s teasing Polonius, it’s all about a daughter, it’s all about this daughter. And Polonius is like, Aha, it is my daughter. And he puts on the play, and he continues this charade. He thinks Ophelia’s being sweet to him when they meet up for the nunnery scene, but then she ends up giving the letters back, and he remembers, Oh, that’s right, this is all according to their plan.

So he has to destroy her for the benefit of the bug [an electronic listening device]. So he just perpetuates their idea by destroying Ophelia. And then at the play that he puts on, by humiliating her in front of everybody. “Lady, shall I lie in your lap? My lady, should I lie in your lap? I mean, my head upon your lap? I mean, with my head in your lap? Do you think I meant country matters?” That’s all just to humiliate Ophelia in front of them to perpetuate this idea that she has driven him crazy, so that they won’t assume it’s anything else.

And so then, the act of finding out, Oh my gosh, that ghost was real. Oh my gosh, my uncle killed my father. Oh my gosh, what am I gonna do? How am I going to avenge my father’s death? That, ultimately, tragically, I think, drives him crazy. So yes, it’s a good question. Is Hamlet mad or isn’t he, that is the question. The answer is: He’s not. He pretends to be. And then he is, because he goes mad.

I think that ultimately he goes crazy because he is tasked with this impossible task, and he misfires, quite literally, and kills Polonius when he hopes to be killing the king. And the act of murder drives him even further into madness. And then, when he is sent away, and he discovers that not only did he see the king see himself in the play, but now he’s seen proof that the king wants him dead, when he unseals Rosenkrantz and Guildenstern’s commission that says: Off with his head. He knows he’s right. He knows the ghost was right. He knows that he has to go back and save Denmark from this maniac. And that is when he is finally sane again.

So when he comes back, when he returns, and you see him with the gravedigger, he’s sane, and he’s ready to lead. And that’s the guy, unfortunately, tragically, that’s the guy that we needed at the beginning of the play. That’s the guy that could’ve stopped all this from happening. But through his own passions and his own privilege, he never grew up. And it wasn’t until all this horrible stuff happened that he had to.

And so when he says to Laertes before they duel, “It was not me that killed your father. It was Hamlet’s madness.” It was my madness, and if that’s the case, then my madness is my enemy too. And I think that’s all totally true, and that’s exactly what happens to him. And that’s what he believes. And in those final scenes, he is no longer mad.

I’d like to talk a bit more about your voice, because in performance it’s so beautifully not butch. You know the way a lot of men will try to talk at the bottom of their pitch range until their vocal cords just wear out, and they get hoarse and gravelly? But for your Hamlet, the whole pitch range is available to you, almost lyrically, all the time. There’s just no boundary that you’ve placed on it. And I love that about it, the freedom of expressivity that it represents. What’s that like for you in performance?

I wouldn’t say that it’s a particular choice. It’s a choice in that I feel like that’s the way to speak this language, and I feel like he is a character who goes through major changes through the course of the play. Emotionally he’s wildly different from scene to scene. And to not employ a variety in voice is, I think, impossible. So to me it is a product of following the thoughts.

When I was at Julliard, we spent many hours in voice classes, finding ways of making clear the text. And a lot of that is vocal variety. And Shakespeare, as you know, is filled with parentheticals and filled with comparisons, filled with metaphor, filled with antithesis, and you can’t just stay on one note all the time if you’re going to do a parenthetical.

When you start a speech and there’s not a period for ten lines, you have to figure out how to get to that period. We would do this exercise where the line was “Shall we all, Valentine do stop chattering, come into dinner?” And we would be urged to find a way with vocal variety to make that very clear. So it would usually be something like “Shall we all (Valentine, do stop chattering) come into dinner?”

We would do exercises like that all the time at school, and I used those things all over this play. It’s constantly in this play. A great example is when I’m throwing Ophelia around in the nunnery scene, after I realize that we’re being spied on, and I say, for the benefit of whoever’s listening, “I say we will have no more marriages. Those that are married already, all but one shall live. The rest shall keep as they are.” And that’s a lot of different thoughts in that one little speech. And if I don’t go all the way up and down my register, I don’t know how else to convey it.

The way I saw your physicality—which that balcony audience member said was like a dancer—was that there was just simply no expressive gesture that you had to censor in order to present as a guy who has no affinity with anything feminine. That was not a concern. By contrast Claudius, in his voice and bearing, is very much the man there in that way.

Yeah.

Sometimes when a male actor is being particularly expressive on stage—especially if it’s not treated in some convention like drag or something—I sense some people in the audience are really taken by it, and some people are a little bit wanting to be at a remove from it, like they’re unnerved.

The things we’re talking about aren’t specific choices I’ve made. They’re just the way it comes out of me. What I do know is that audiences at Hamlet laugh at the famous lines. They just can’t help it. When they hear, “There’s something rotten in the state of Denmark,” they laugh. When they hear, “Get thee to a nunnery,” they laugh, even though those are not funny lines. And I find they also will laugh at things that aren’t funny because they get them. And I think that there’s something about clarity that is amusing to people, and they delight in it. Shakespeare is not easy, and a lot of audiences, especially adults, come to see Shakespeare with a wall up to an extent, because they know it’s gonna be hard. And they delight in understanding things.

And I think that’s something this production does. When the lights come up and you see a guy in a security-guard jacket watching TV monitors, you get it. And they delight in that and they laugh at that. They think, Oh my gosh, I get this.

And so I think perhaps this vocal variety and physical storytelling that you’re picking up is occasionally delighting people and making them laugh, and they might perceive it as being funny. But what it really is, is they’re just getting it, and it’clear to them. And perhaps I’ve been given license to be free by Michael Kahn and by our production, and that’s how it’s coming out.

I think it’s very exciting, what you’re talking about. If it means that any boy or young man that comes to see this play thinks, I can be a man and not have to use the lower register of my voice and keep my arms at my side, then I’m very excited by that.

Running Time: 3 hours, including one intermission.

Hamlet plays through March 4, at the Shakespeare Theatre Company, performing at Sidney Harman Hall – 610 F Street, NW, in Washington, DC. For tickets, call (202) 547-1122 or go online.

LINKS:

‘Buyer & Cellar’ at Shakespeare Theatre Company by

Schmoozing with Michael Urie About ‘Buyer & Cellar’ at Shakespeare Theatre Company by