When is art an intentional expression of respectful cultural appreciation and when is it an unconscious foray into cultural misappropriation?

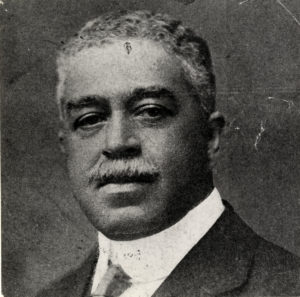

These were some of the deep questions raised in Deep River: The Art of the Spiritual, a classical sacred concert at the Washington National Cathedral in tribute to Harry Burleigh, African American classical composer, arranger and acclaimed baritone. The program was presented in collaboration with the PostClassical Ensemble, an experimental orchestral laboratory.

The last day of Black History Month was perfect timing to spark a much-needed conversation about cultural ownership at this moment in America’s history. With the “Black Panther” phenomenon still thrilling moviegoers around the world with its Afro-futuristic pride, “Deep River” was a glimpse into the soul of African American “sorrow” or “plantation songs” that left me wondering whether the Negro Spiritual had forfeited its authenticity for the glamor of the concert stage by a classic, Eurocentric presentation.

Circa early 1900s, Henry Thacker “Harry” Burleigh overcame racial discrimination to go on to become the personal assistant to the director of the National Conservatory of Music in New York City, the famed Czech composer Antonin Dvorak. It is interesting to note that Burleigh seems to have had little direct exposure to deep Southern culture, the origins of the Negro Spiritual. But nevertheless, he obviously felt a deep affinity with the music of his enslaved grandparents, despite having grown up among the predominantly white working class of the small town of Erie, Pennsylvania.

Attending the National Conservatory on a music scholarship, Burleigh used to sing Negro Spirituals while cleaning the halls as a janitor during his musical education. Dvorak heard Burleigh’s sonorous baritone voice and the unique rhythmic creativity that he gave to the songs. Burleigh’s arrangements prompted Dvorak to explore this musical genre as the catalyst for his own classical creations.

The “New World Symphony,” Dvorak’s seminal orchestral composition, included strong elements of Harry Burleigh’s astute musical creativity. Burleigh’s arrangements matched any of the high-brow music intellectuals of the day.

Harry Burleigh’s “Deep River” arrangement debut became an iconic presentation of a Negro Spiritual. And thus Burleigh was responsible for bringing the Negro Spiritual into concert halls around the world by famous singers and musicians who performed them in the early 1900s.

Burleigh also published his own songbook of hundreds of art songs that were the spirituals and romantic love songs well suited for the classically trained singers and musicians who popularized his works.

“Deep River: The Art of the Spiritual” as a musical concert was somber and solemn in its comportment from start to finish. I was not always certain whether this was a secular music concert or a mid-week religious service filled with sacred music in the Washington National Cathedral. Clapping hands felt somewhat awkward because of the religious atmospherics but the singing was beautiful, deeply fervent, and the acoustics of the cathedral sent vibratory waves of pleasing echoes throughout the sacred hall.

What was crystal clear from the start, however, was the powerful impact of Kevin Deas, bass-baritone soloist, upon the entire presentation. The Washington National Cathedral Choir, under the direction of Angel Gil-Ordóñez, entered the cathedral solemnly walking down the center aisle in long purple robes with Deas’ booming voice adding to the pageantry of the procession.

The entrance alone transported you to a time in history of reverence and intense religious fervor for battles fought and won in the name of tolerance. The program felt like a living, multi-media history lesson with full-bodied narration by local mezzo-soprano, Kehembe V. Eichelberger, and video scripts of plantation still art scenes and audios of Burleigh’s actual vocals presented by Peter Bogdanoff, video artist.

Most of the program was sung a capella other than the opening songs, “Sinner Please Doan Let Dis Harves Pass”, “Sometimes I Feel like a Motherless Child” and “Steal Away” with Kevin Deas solos accompanied by Joseph Horowitz on piano and Herbert Fletcher on flute.

The celestial Washington National Cathedral choir really needed no accompaniment as they sang a heavenly program of songs including “My Lord What a Mornin,” “O Holy God,” “Ezekiel Saw de Wheel,” “There is a Balm in Gilead” and “Go Down Moses.”

In the finale, young choristers from the Metropolitan AME Church, Woodrow Wilson High School, Oakland Mills High School, Long Reach Middle School, and Wilde Lake High School added a futuristic element to a program honoring a man from the past who brought the Negro Spiritual from the field to the concert stage. They closed the program with Kevin Deas adding solos to the full choirs on “Goin Home.”

Burleigh’s “Deep River” song was sung several different times during the evening. Its repetition seemed to highlight the intelligent musical potential of Burleigh’s arrangement of this old Negro Spiritual which lent itself to a variety of musical interpretations. Deas sang an arrangement alone, we heard an audio of Harry Burleigh singing it, and four other different arrangements including mixed chorus, male chorus, and another by the conductor, Angel Gil-Ordóñez.

To my ear, however, “Deep River” sounded pretty much the same regardless of who was the arranger. And this was perhaps the greatest challenge of this program — presenting only classical arrangements by an almost all white Washington National Cathedral choir that did not sound like Negro Spirituals.

The arrangements of this program were filled with emotion, spirituality and reverential respect but they still lacked the essence and the energy of the old-time Negro Spiritual. The vibration in the cathedral hall was heartfelt but the mood was too sad and somber to reflect the true Negro Spiritual as I have known them.

African Americans were sorrowful during their enslavement but in singing their spirituals they always looked beyond their suffering for better times to come. Negro Spirituals are quintessentially inspirational, uplifting and filled with hope. But I felt little of this in an overly solemn, strictly classical presentation of the genre. The program did not transport me to better times.

I left Deep River: The Art of the Spiritual asking myself, “Whose art?”

Running Time: One hour, with no intermission.

Deep River: The Art of the Spiritual with PostClassical Ensemble played for one night only on February 28, 2018, at the Washington National Cathedral – 3101 Wisconsin Ave., NW. Check their calendar for upcoming events. For tickets to upcoming Cathedral events, call the box office at 202-537-6200 or purchase them online.

Preach Rev. Harper! I felt like a ‘Sparrow’ in the rafters reading your ‘Tough Love’ review.

Ms.Harper’s understanding of the art form of the Negro Spiritual, married to her lived experience, prompts this criticism provided by her in equal measures encompassing and intelligent. Quite consistently, her writings are worthy of the highest levels of literary regard and scholarship. In my vew, not to be lost in the audience’s experience of the performances delivered at the National Cathedral on February 28th by the Post Classical Ensemble, is the didactic nature in construction of the programming, and the witness to Burleigh’s influence on a not-insignificant trajectory in American music, as expressed in so very many faith communities in our nation each and every Sunday. That many non-Negro or non-Black composers and arrangers would engage in the pathing from Negro Spirituals to American spirituals gives the finest testament to the monumental influence of Burleigh on the course of this important genre of the art form of the Negro Spirituals in 20th and 21st Century American music.

Thanks for the insightful review and I also agree with the comments made. A few small corrections: Burleigh did not start making spiritual arrangements until after he graduated from the National Conservatory of Music, so what he sang for Dvorak would have been just the spirituals as he learned them from his grandfather. The spiritual that we heard Burleigh singing was “Go Down, Moses” (which was the only recording he ever made) and not “Deep River”. And the program was 90 minutes long. I agree that Burleigh’s arrangements helped to influence many non-Black composers and to bring spirituals to a broad, worldwide audience. At the same time, in future iterations of this program, I think that PostClassical Ensemble might consider including more traditional styles of spiritual performance as well, i.e., call and response, fast and rhythmic, as well as the predominantly slow ones we heard at the concert. This inclusion would give a clearer sense of the source material that Burleigh was working from. And PCE has included Hungarian folksongs in their programs on Bartok, flamenco songs in their programs on Falla, and Mexican folksongs in their programs on Revueltas, so the precedent is there. I give them many kudos for putting on this program and broaching the topic of race and music, when so many music groups in the area are not doing so. I hope that it can continue to generate fruitful, if at times difficult, dialogue and discussion. They will continue programming on the topic of race in classical music on April 20-21 with two programs at Georgetown Universityy on Afro-British composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor and his visits to Washington from 1904-1908: http://postclassical.com/performances/ethopia/