“This concert series is dedicated to Russian chamber vocal music, which is rarely heard in America,” states the program; a regrettably true state of affairs. The Russian Chamber Art Society (RCAS), whose motto is “music without borders,” memorably remedied this for the audience at the most recent of its concerts Friday night at the French embassy.

The program was carefully crafted, beginning with the more expected—three vocal pieces, sung by Bass Grigory Soloviov and accompanied by RCAS Founder and Artistic Director Vera Danchenko-Stern on piano and Anna Kusner on guitar. It continued, in a surprising but delightful jolt, with the unconventional: six wildly varied works, from a folk song arrangement to a selection from a Shostakovich operetta, by the Russian Trio (more on them below). Mezzo-soprano Susana Poretsky followed with three vocal pieces and was then joined by Soloviov in a duet. The second half both balanced and reversed the first, the groupings similar but the order switched.

From the opening selection, “Shine On, Shine On, Oh, Star of Mine,” a paean to a loved one by the mid-19th-century composer Pyotr Bulakhov originally written for tenor voice but subsequently popularized by basses, Soloviov, Kusner and Danchenko-Stern formed a musical, emotional and artistic partnership that would characterize the seven performers and their performances throughout the concert, and would find emotional consonance with the demonstratively appreciative and enthusiastic audience.

“Oh You, Night,” an unaccompanied folk song depicting one who is seeking rather than extolling love, gave Soloviov a chance to connect more directly with the audience, which he used to his advantage with a personally declarative tone enriched by a firm, controlled vibrato, ending in a ringing top note.

In I. Shyshov’s “Four Winds,” a surging, raging summons to the elements with a steady, “Volga Boatmen”-like beat, Soloviov’s emphatically thrusting arms, twisting mouth, fiery eyes and commanding voice, while ostensibly calling forth the springtime, also evoked a fiery darkness recalling the titular character in Boïto’s “Mefistofele.” Here, as always, her eyes as carefully trained on the singer as on the music and her own figuratively, yet almost visibly flying fingers, Danchenko-Stern, the master teacher aspect of her capacities coming to the fore, provided powerfully and invaluably intuitive support, while Kusner’s guitar-playing evinced a skill that seemed at once innate, attained and proficiently applied.

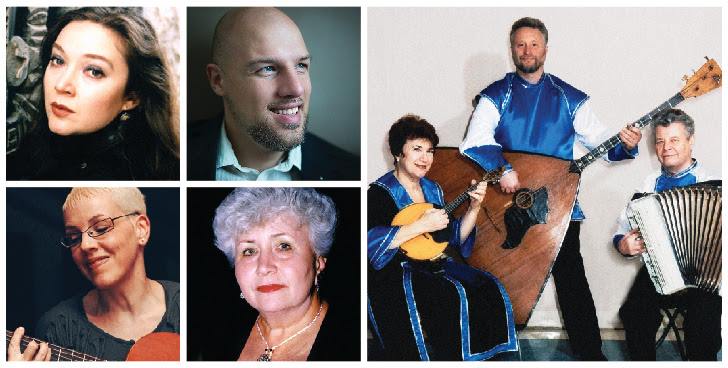

As did that of The Russian Trio’s three members: Tamara Volskaya, on the lute-like domra; Anatoliy Trofimov, on the accordion-like bayan; and Leonid Bruk, a visual standout in silky, electric-blue top with puffy white sleeves, his white hair coiffed in a pompadour, on the imposingly large, triangular contrabass-balalaika. From “Tyorskiye Chastushki,” an old Russian song, through Russian romances; from the famous (Tchaikovsky’s “March from The Nutcracker” and “Neapolitan Dance” from Swan Lake) through the less so (“Galop” from Dmitri Shostakovich’s operetta Moscow Cherry Tree Tower), the joy and agility with which Volskaya’s lightning-quick fingers strummed, picked and plucked was infectious, as was the intensely bouncy beat of Bruk’s balalaika, with Trofimov, his eyes never leaving Volskaya’s fingers, providing a quiet, steady pulse.

Opening with “The Burgundy Shawl,” Poretsky (in shades of dark red satin, as was Danchenko-Stern) impressed with an effective chest voice, which she would take to greater heights (and depths) in A. Aliabyev’s “The Beggar Woman.” Like the despairing lover in “Shine On,” the doubtful one in “Oh You, Night” and the desperately seeking solitary man in “Four Winds,” this woman is, by virtue of her plight, a sympathetic character. But she is more. Much like the immortal Norma Desmond in Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard, or the erstwhile opera singer Pellegrina Leoni in Orson Welles’s unfinished film The Dreamers, this sorrowful one was an actress who once led a charmed life, only to become ill, losing “her voice and vision” so that she now “wanders around the world alone.”

Poretsky and Danchenko-Stern, of course, had no need to find paradigms or parallels in Western literature to know this woman; Russian storytelling is a rich vein, a mother lode of characters and tales such as these. The singer and pianist conveyed the beggar woman’s story with declamatory skill and urgency, Poretsky’s voice rising and at times half-speaking, as if addressing the audience directly, drawing us, Danchenko-Stern a visceral and technical comrade-in-arms, compellingly into the drama. N. Shyriayav’s “To Love, Embrace and Cry Over You” was true to its name, as was Poretsky, whose deep, sumptuous tones brought home the anger and anguish of the song, as did a burnished, glowing high note.

“Insane Nights” by A. Spiro featured a sort of dual duet: Poretsky and Soloviov joined by Danchenko-Stern and Kusner, and in a way that could not have been less true to its title: The voices blended beautifully, their textures and colors complemented by the instruments’ tonal fidelity, the performance made even more absorbing by their sonic diversity.

Poretsky returned to the stage after intermission with “Only Once,” by the early-to-mid-20th-century composer B. Fomin, another passionate evocation of love’s joys and pains. Poretsky shone, her voice richly dramatic, the top notes again clear and ringing, but here, verging on screaming—yet of the most technically and effectively deliberate, affectively heart-rending kind.

A feeling that was quickly offset (with Poretsky’s instantaneous attitude adjustment) by the gypsy song “My Friend, the Guitar,” which had a number of apparent native speakers, who may have appreciated nuances discernible only in the original, chuckling drolly. (For an English translation, think Joni Mitchell’s “Songs to Aging Children Come.”) What sold this writer was Poretsky’s bracing, rhythmic delivery laced with Piaffian rue, its pièce de résistance a spine-chilling high note.

For D. Pokrass’s “All That Passed,” Poretsky was accompanied not only by Danchenko-Stern and Kusner, but by Bruk on contrabass-balalaika, with all four musicians digging deep into their Russian roots, revealing an earthy, kozachok-like, well-nigh-irresistible intensity that had many in the audience clapping in time with its heavy, steady rhythm, erupting in cheers and applause at the end.

If seeing Shostakovich and operetta in the same sentence may seem unlikely for listeners accustomed to hearing works more characteristic of his neo-classical side, it may come as a surprise that his “Galop” would have been worthy of Offenbach. Here, Volskaya’s impeccably precise scales, trills and pizzicati, played with head-spinning speed at the zenith of the instrument’s reach, were awe-inducing. While Shostakovich’s “Festive Dance” (or Spanish Dance) from the 1955 Soviet film The Gadfly, is not, when played as written for a full orchestra, overly arresting, the arrangement devised for (and perhaps by) our company of three had heads swiveling and eyes and ears marveling, trying to stay abreast of the fast-paced sonic and stylistic shifts and instrumental hand-offs while reveling in the way such utterly disparate parts could be so essentially integrated, so ineluctably part of a whole.

But: speaking of film! Reading that the next number would be the same composer’s “Waltz from Jazz Suite” did not prepare this reviewer for what has come to be known by moviegoers as the theme from Stanley Kubrick’s 1999 film Eyes Wide Shut—or for the simple, classic elegance with which it was played. Just as having heard Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov’s daunting showpiece, “Flight of the Bumblebee,” once a staple of TV talent shows, did not lessen in the least the astonishment of hearing it performed not by one instrument but two, and neither of them with flexibly pluckable strings: Trofimov’s bayan and Bruk’s balalaika. It was as if the onetime showpiece had morphed over time into a showdown—between dueling bees. In contrast, the Siberian folk song “Welcome to My New House” offered a deceptively mellow lilt, which then slid suddenly into an off-key iteration and back again in a masterful display of the three players’ musicianship.

As were Soloviov’s three concluding folk songs further demonstrations of his own and Kusner’s. “There Goes the Three-horsed Sleigh,” yet another fiery lament for love lost, recalled the dynamic range and tone, the heartbreaking passion and intensity of the great Russian bass Feodor Chaliapin, ending in a startling hush. Its mood was swiftly swept from this listener’s mind by “Eh, Nastasia,” a musically and lyrically schizophrenic piece in which the singer graphically recalls, and Soloviov grippingly personified, the agonies and ecstasies of love. He and Kusner were so closely aligned as to be musical peas in a pod, from which at its rousing conclusion they popped, triumphant.

“Along Peterskaya Road,” a charming little ditty, gave Soloviov another opportunity to connect more personally with native Russian speakers: While the rest of us took great pleasure in his broad smile, expansive gestures and vocal prowess, a widely scattered segment of the audience laughed, some whooping uproariously (if, in respect for the venue, somewhat sotto voce) at things that sailed blithely by those of us who relished the experience but felt a bit like tots who’d snuck into a PG-13 movie: having a really awesome time, but a sneaking suspicion that we may have missed out on the really good parts.

No such ambivalence was aroused by the program’s closing songs, by the late-19th-century composers A. Dubuk by Boris Sheremetyev, respectively, and sung by Soloviov and the returning Poretsky—not just with, but to each other. In “My Sweet Heart,” the two singers played off each other to exemplary effect, alternately celebrating and castigating the other and themselves in a way that would have felt at home right on Broadway or at the Met (or the Warner or the WNO-Kennedy). With “I Loved You So,” the mood again shifted at lightning speed, serving as both summation and amplification of the program’s themes. Imbued with a warm and graceful nostalgia, the two voices—this time, in English—recalled in tender tones the love they’d shared, now wishing the same for each other, should there be one day another. Soloviov and Poretsky’s voices blended softly, gently; generously, and harmoniously, giving a long-awaited, well-earned and well-deserved repose to the “Restless Heart” to which the rest of the concert had paid earnest, exacting, and exciting tribute.

Running time: One hour and 40 minutes, with one intermission.

The Restless Heart: A program of Old Russian, Gypsy (Romani) and Folk Songs of Passion, Longing and Love was performed on Friday, April 27, 2018, at The Embassy of France, 4101 Reservoir Road NW, Washington, DC.