Among the rich offerings in The Kennedy Center’s Artes de Cuba festival were two extraordinary works of theater, each performed but twice: The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant, from Teatro El Público, and 10 Million, from Argos Teatro—both companies based in Havana. I saw Petra at its first performance, in time to post a review before its second (“a zippy-campy live-action cartoon befitting someone certifiably crazy in love,” I called it). Impressed with Petra, I then decided to check out 10 Million, which I caught at its second performance. And wow, what a provocative double bill!

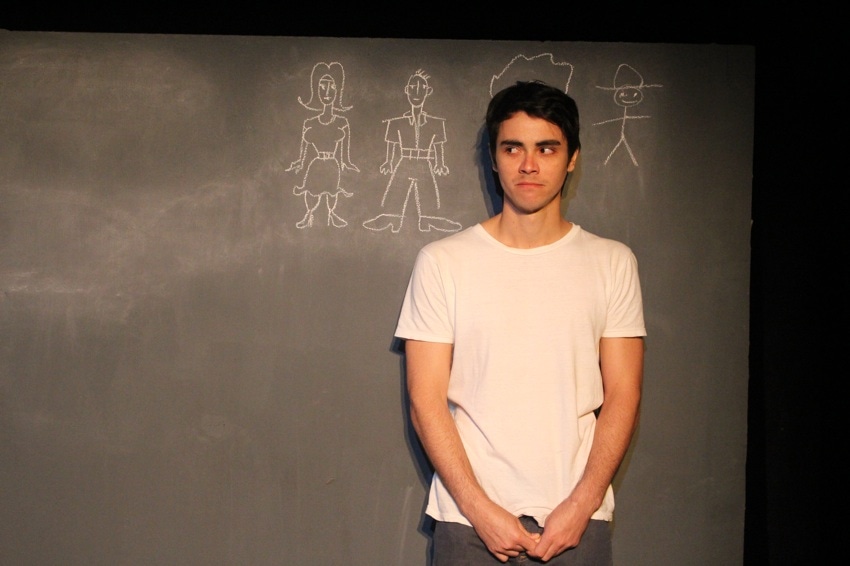

If I could have reviewed 10 Million in time to urge more people to see it, I would be raving about the performance of Daniel Romero as He, the central character. 10 Million—which takes its name from Castro’s overreaching target for the 1970 sugar harvest of 10 million tons—is an autobiographical theater piece created by the renowned Cuban Writer-Director Carlos Celdrán. The set (designed by Celdrán) is stark, uniformly gray, stepped platforms and a back wall that serves as a chalkboard. There are three others in the cast: Maridelmis Marín as Mother, Caleb Casas as Father, and Waldo Franco as Author. All have passages of first-person and narrative direct address to the audience, so we get to know them each as characters and as actors, and all are excellent. But Romero is the magnetic young man who commands our attentive concern, propels the emotional momentum, holds together the whole show—and not just because he strips down for onstage costume changes. He compares to a younger Gael García Bernal and he may be even better.

But wary that “here’s what you missed” recaps of short runs can be a frustrating read, I’ve chosen instead to reflect on the experience of seeing the two works sequentially: On that point what struck me most was how dramatically, openly, and differently they each handled a central character’s gender nonconformity—and how relatedly sexual politics played out in each work’s theatrical world.

The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant is the story of an unrequited same-sex obsession set in a world of high fashion, and 10 Million is a coming-of-age story about a probably queer boy set against the Cuban revolution. Both works have origins in a gay artist’s autobiography. Petra is based on the 1972 film that thinly disguised German filmmaker Ranier Maria Fassbinder’s own unrequited sexual obsession with a young man. The play 10 Million is explicitly about several decades of Celdrán’s life beginning as a preteen in the 1960s.

In style of presentation, the two works could not be more different. Petra is done in outlandish and gaudy drag, its emotions over the top; 10 Million is relayed intimately and dreamlike, its emotions couched in the personal voice of Celdrán’s journal. Yet between the two works is a resonance about gender dissonance that still plays in my mind.

There are several nesting boxes of gender variance in Teatro El Público’s production of Petra: a gay man’s story first told in a film through lesbian characters has been adapted for the stage with the female characters played by men. As in nearly all drag, when men playing female are performing male projections of women’s lives, Petra on stage entails a degree of microaggressive misogyny costumed as admiration. The presumptive upside of such theatricality, or so the argument goes, is that by revealing gender to be performativity, it destabilizes hegemonic gender. The counter-argument is that by exploiting misogynist tropes, drag serves to congeal gender hierarchy. This debate has raged for decades and I raise it not to resolve it but to point out that viewed in the context of a society suffused with toxic macho, the sexual politics in Teatro El Público’s Petra are flamboyantly against the gender grain.

In 10 Million, the character He is the child of a bitter divorce. We first meet him during one of the months in summer when his Mother has agreed to let him visit his Father. The boy’s relationship with his Father is portrayed as loving and deeply tender; the boy’s relationship with his Mother, strained and borderline abusive. She is a rising star in the Revolution, a beautiful, domineering, and driven woman captain, who disdains what she perceives as weakness in her ex-husband for his disinterest in politics. Mother’s antagonism toward Father leaves the boy fearful and ashamed, and things take a turn for the worse when she determines that the boy himself needs to be toughened up on account of “his strange behavior.” The play never actually says the boy is gay but it doesn’t need to. He is shipped off to an all-male boarding school for “therapy” where he is all alone, “the new one, the weird one,” and thrust into boxing matches and other brutalizing means to make him man enough for the Revolution. In one of the play’s many telling scenes, the boy is instructed to draw a man and a woman on the chalkboard. He draws stick figures. As if to humiliate him, the teacher then draws a female with breasts and hips and a male with broad shoulders.

For most of 10 Million, the Mother as written is a cold-hearted ballbreaker who tries to turn her son against his Father. “A woman with power is stronger than a man with power,” she says. Celdrán gives the Mother a passage near the end when she speaks of her disappointment in the Father and her regret that she married him with what seems intended to make her character somewhat sympathetic. But for the most part she’s anything but, and since she is Celdrán’s creation, his report is all we have to go on.

What’s fascinating to me is the way both Petra and 10 Million both play into and upend gender norms. Neither goes so far as to be what I would call revolutionary, but seen in the context of the Cuban Revolution, nor are they status quo.

I cannot say whether the programming choice to pair these two works was made so that if experienced side-by-side they would stimulate a mental conversation about revolution and gender. That’s certainly not what I would have expected to come out of Cuba, given the country’s reputation for not being particularly LGBTQ friendly! But if opening DC audiences’ eyes to a newly opened Cuba was at all a festival objective, count it a smashing success for at least this one theater lover.

Running Time: Two hours, with no intermission.

10 Million played two performances, May 19 and 20, 2018, at Argos Teatro performing at The Kennedy Center’s Family Theater – 2700 F Street, NW, in Washington, DC, as part of the Artes de Cuba festival, which runs to June 3, 2018.

For tickets to upcoming events, call the box office at (202) 467-4600, or Toll-Free: (800) 444-1324, or purchase them online.