The Rude Mechanicals production of The Merchant of Venice, now playing at the Greenbelt Arts Center, is an engrossing exploration of Shakespeare’s most controversial characters and the (still) relevant social issues they negotiated in the late 1500s in Venice. Director Claudia Bach uses a pared-down set and minimal props to magnify the nuanced dialogue. This technique elucidates both the complexity of the characters and the social dilemmas they face (whether the love within them can conquer the prejudice, hubris, greed, legalism, hatred, and hypocrisy that also lies within). In her director’s notes, Bach asks, “What if we moved aside the gold and silver caskets, the carnivals of Venice, the wealth of Belmont, and any and all preconceptions about what this play is about and what these characters are like?” Her answer is an honest and true representation of the complexity of the characters and the issues with which they wrestle, ones that we still grapple with more than 420 years later.

The plot pivots around a financial agreement between two merchants in Venice. Antonio, a Christian shipping merchant, wagers more than all he has on his dear friend, Bassanio, by taking out a loan from the other merchant, Shylock, a Jewish moneylender who has suffered prejudice from the majority Christians amongst whom he lives and is seeking revenge. Antonio’s fortunes are tied up in his shipping business with four ships at sea. Antonio borrows the money from Shylock and promises to pay him back with a pound of flesh if he can’t pay in cash in three months’ time. Bassanio then borrows the money from Antonio to woo Portia, a wealthy heiress who has to marry according to the wishes of her deceased father. Her father willed that the first acceptable suitor who chooses the correct from three possible chests, one gold, one silver and one lead, would become her husband. Portia hopes that Bassanio, a fellow Venetian, will guess correctly for she doesn’t want a foreigner for a husband. Meanwhile, Shylock’s servant Launcelot no longer wants to work for the Jew, and Shylock’s own daughter, Jessica wants to leave her father and elope with the Christian, Lorenzo.

While this is the crux of the drama, The Merchant of Venice is ostensibly a comedy and so love abounds. However, many of the romantic relationships that symbolize love contravene convention and the social issues and their solutions contravene love itself. Antonio is in love with another man; Bassanio is in love with Portia for her money; the Christian Lorenzo is in love with the Jewish Jessica; and love, that lofty “Christian” ideal that includes self-sacrifice, tolerance, spirituality, humility, and mercy, is at odds with everything else–and each of the characters seems to have only a little love and a lot of everything else within themselves. For example, we see Antonio’s self-sacrifice for the sake of Bassanio, who selfishly accepts Antonio’s sacrifice. But Antonio is only sacrificing for his own selfish desire of winning Bassanio’s love.

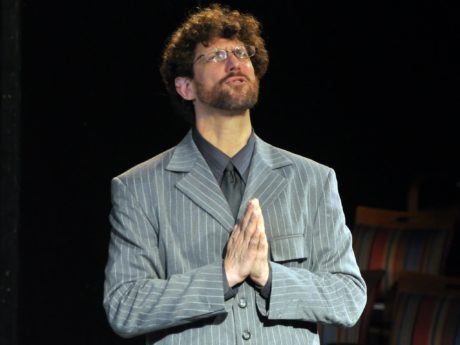

Compelling performances render elaborate sets and props superfluous. During the trial scene, Jaki Demarest (Antonio) sheds anguished tears as she prepares to give her pound of flesh and Joshua Engel (Shylock) masterfully transitions from merciless loan shark to defeated Christian convert in seconds. Engel’s evil laughter while suggesting to Antonio, “let the payment be a pound of your flesh,” makes his Shylock seem like the exact devil that his servant Launcelot claims him to be.

Allison McAllister (Portia), Sarah Pfanz (Gratiano) and Wes Dennis (Arragon) provide comic relief with perfect timing and gestures. McAllister performs an exceptional portrayal of a Portia who has become accustomed to being in charge of her household but is faced with gaining a husband from a flawed field of candidates. She uses sarcasm like a scalpel, cutting up her would-be suitors with acerbic remarks. After meeting two of the candidates who have come to try their luck at the chests of gold, silver, and lead, we laugh with her as she states, with a wry smile and a hand on her hip, “for there is not one among them but I dote on his very absence.”

Sarah Pfanz plays a boisterous and lively Gratiano, mischievously chiding Antonio for being melancholy, “Why should a man, whose blood is warm within, / Sit like his grandsire cut in alabaster?” Later, deciding on a whim to marry Nerissa, Portia’s maid, Gratiano states, “You saw the mistress, I beheld the maid.”

Wes Dennis’ portrayal of Arragon as he tries to decide which chest to open is highly entertaining what with his stomping of his feet and exaggerated posturing. His consideration of each word on the scrolls combined with the proper facial expressions creates not only an amusing, but also an enlightening scene.

The choreography for the opening ritualistic dance and the music selections at each of the chest opening scenes and intermission are excellent. The circular dance, something between a pagan sacrifice and musical chairs, is an apt metaphor for the prejudices against Shylock and Antonio. “You don’t own me,” is a fitting theme song for Portia and “Glitter and Gold,” by Barns Courtney, is seemly for the play overall.

This is not a classical interpretation of this play. All actors use American accents. The costumes consist of plain, black pants to signify male characters and long black skirts to signify female characters. The only props are five gilt and black painted chairs and three of the actors portray the three chests of treasure, signified by the applicable actor wearing a gold cap, a silver cap, and a gray cap.

But all of the elements in this production of The Merchant of Venice work in harmony to amplify the themes of complex human nature through dialogue and action. This allows the audience to ponder the meaning and weight of it, leaving it with much more than a pound of flesh. Instead, the audience gains a whole artistic and philosophical meal to chew on.

Running Time: Two hours, with one intermission.

The Merchant of Venice runs through June 30, 2018, at Greenbelt Arts Center – 123 Centerway, Greenbelt, MD. For tickets, call the box office at (301) 441-8700, or go online.