One of the myriad things Lin-Manuel Miranda does so beautifully in Hamilton: An American Musical is his portrayal of the profound symbiosis among the Schuyler Sisters: Angelica, Eliza, AND Peggy. The sisterhood has captivated women across America. With a kind of defiant delight, fans quote Miranda’s wonderfully proto-feminist lyrics: “I want a revelation,” and “include women in the sequel.” Teens strike the sassy peace-sign/snap pose of the trio’s reprisal: “Work!” With this as their pop culture vernacular, Miranda may well be responsible for a whole generation of young women now determined to “be part of the (national) narrative.”

Of course, art interprets a life story for its humanist statements. How much of what Miranda presents about the sisters is true? Let’s start with what is: Eliza.

Miranda’s dedication to accurately dramatizing history shows best in his portrait of Alexander’s loving wife. “Who lives, who dies, who tells your story?” For Hamilton, it is unquestionably Eliza, and with poetic justice, Miranda ends his musical with Eliza center-stage.

Without her devotion to organizing his papers, Hamilton could easily have been relegated to the trash-heap of political scandal or tangential founding fathers – (we don’t discuss many of them enough, including the Schuyler Sisters’ father, Philip). Interestingly, in gathering his correspondence, Eliza saved Angelica’s letters to Alexander, but not her own – a lack Miranda represents in her heart-wrenching reaction to the Maria Reynolds affair, the tour de force “Burn.”

Perhaps the real-life Eliza worried her letters couldn’t match his eloquence. Few could. Hamilton’s missives are exquisite – lyrical, laced with classical references, angsty idealism, braggadocio, and an endearing vulnerability. (Read them here.) In his love letters, Hamilton often chided Eliza for not writing him more frequently and more candidly. (His are quite candid! So much so his children felt the need to edit them for posterity’s eyes.)

Angelica’s letters, on the other hand, went toe-to-toe with Hamilton’s in philosophy and clever flirtatiousness. The comma-play, for instance, that Miranda presents in “Take a Break,” (which he has jokingly called “comma sexting”) was actually an implied endearment penned by Angelica, known admiringly by her contemporaries as “the thief of hearts.”

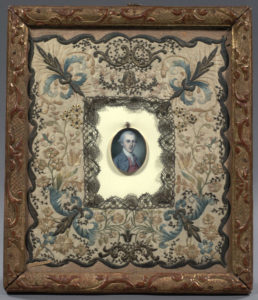

Family letters that do survive reveal the younger Eliza could be prone to bouts of anxiety. That fact makes even more extraordinary Eliza’s surviving with such dignity and strength her son’s death and then Hamilton’s public infidelity, reputation-suicide, and fatal duel. Eliza does live another 50 years, raises their remaining seven children alone and in poverty (one debilitated with crushing depression), builds an orphanage, raises money for the Washington Monument, and keeps Hamilton’s Revolutionary legacy alive. Fellow aide-de-camp, Tench Tilghman—who seemed a bit smitten himself with the middle sister of the “dark-eyed, amiable” Schuyler trio—aptly dubbed Eliza “the little saint of the Revolution.” The frame for Alexander’s portrait she embroidered as her wedding present is a lovely symbol of what Eliza saw as her life’s work.

Eliza was an accomplished artist in other mediums as well. We know that because Hamilton refers to her miniature portrait of Peggy when he writes and begs the younger Schuyler sister’s help in courting Eliza. Saying he has already formed “a more than common partiality” for Peggy’s “person and mind” from Eliza’s painting and descriptions, Hamilton playfully begs Peggy, as a “nymph of equal sway,” to come distract the other aides-de-camp so he can monopolize Eliza. That’s right, in real life it was Peggy (not Angelica) who was Alexander’s confidante in romancing Eliza at that fateful “Midwinter’s Ball,” February 1780.

Here’s where Miranda diverged a bit from fact: Angelica was already married and the mother of two toddlers when Alexander Hamilton entered the tightknit circle of the Schuyler Sisters.

Although that fact may upset diehard Angelica-fans, to be fair, there are only so many details, characters, and subplots that can be crammed into a two-and-a-half hour musical! Miranda’s condensed version of the Revolution’s history and founding fathers is nothing short of miraculous. Also, his Schuyler Sisters song encapsulates so well the giggly, Jane-Austen style us-against-the-rascals-of-the-world bond among the three girls. Given Hamilton’s long intellectual love affair with Angelica, it was appropriate for Miranda to focus on her and minimize Peggy’s role.

However, the real-life Peggy was just as smart, well-read, and spirited as the more famous Angelica. And of the three, Peggy was the only sister in the right place at the right time to witness the constant surge of spies, couriers, and Iroquois delegations to her father’s Albany library – which really was “the room where it happened” during the earlier years of the war.

Called “a wicked wit,” “endowed with a rare accuracy of judgment in men and things,” Peggy was a feisty “favorite at dinner tables and balls” and even dashed into the fray of an attempted kidnapping of her father – (who was GW’s right-hand man for espionage!) – to save her baby sister. She was fluent in French, had a romance with a French officer who was one of only eight people honored with a Congressional Medal during the Revolution and taught herself basic German by reading her father’s engineering manuals. One of Hamilton’s closest friends (James McHenry, of Baltimore’s Fort McHenry) criticized Peggy as being a “Swift’s Vanessa” – 18th-century code for a woman too keen on talking politics with men to be entirely likable! “Tell her so,” McHenry wrote Hamilton. “I am sure her good sense will soon place her in her proper station.”

“My Peggy” as Hamilton called her in letters to Eliza, (in which he dropped affectionate bits of gossip about his new little sister), never heeded McHenry. In that regard, Peggy was very like her eldest sister.

In answer to Hamilton’s letter, Peggy bodaciously rode out into the worst winter ever recorded in American history, through 4-to-6-foot snowdrifts and frost-bite cold to reach Morristown, NJ. Perhaps Peggy feared the man wooing her gentle middle sister was another dangerously charming rogue, like the man Angelica had fallen for three years earlier.

Angelica’s choice in husband is perplexing, frankly. In 1777, when her father was General of the Northern Army and desperately trying to counter a British invasion from Canada, Angelica eloped with a man who’d been sent by Congress to check her father’s accounts, accusing Schuyler of poor command. Needless to say, Schuyler didn’t much like the guy. Her suitor was also cloaked in mystery, having recently fled England, either to escape gambling debts or retribution for a duel, and adopted an alias, John Carter. It’s unclear whether the Schuylers knew this. In any case, Carter’s hasty emigration doesn’t come across as sincere revolutionary fervor promising Thomas Paine style “revelation.”

Eventually, Carter did play an important role in the Revolution, as commissary for the French Army. But he also amassed a fortune doing so. As such Carter would be a controversial patriot at best.

So why him? Angelica’s father “was loaded,” one of the richest and most influential men in upstate New York, so there was no need for his firstborn “to social climb” or “to marry rich” for the family’s sake. And in 1777, Carter didn’t offer any of that.

When she met Carter, the war’s battle lines had relegated Angelica to the frontier town of Albany. After enjoying years in the intoxicating roil of New York City, she was probably bored silly. Carter was handsome, with eyes to rival Hamilton’s legendarily luminous ones, and certainly London-sophisticated. Whatever courtship they had would have been breathlessly short. Clearly, Angelica was a tad willful, decidedly a romantic. So while Miranda may have changed the specifics of her early life to fit his musical’s time-constraints, he completely captures the yearning intellectual and scintillating conversationalist Angelica was and the quick, deep affinity she felt for Hamilton. Miranda’s presentation of the fierce loyalty among the Schuyler sisters, no matter what wedge a man might drive between them, is also spot-on.

If anything, the reality of Angelica’s youthful and impetuous marriage makes the intellectual magnetism between her and her brother-in-law even more poignant. She became his political muse (as well as Thomas Jefferson’s). Biographer Ron Chernow speculates that Angelica fed Hamilton’s mind while Eliza gifted him kindness and unconditional love. Peggy was a friend—perhaps the only woman in Hamilton’s life with whom he did not engage in double entendre. Lots of affectionate teasing, yes, but very much that of a knowing big brother to a strong-willed and vivacious younger sister. Hamilton, in fact, was with Peggy when she died, too young at 42. His loyally championing her husband’s candidacy for New York governor after her death is part of what led to Hamilton’s duel with Burr.

One last heartbreaking irony in Hamilton and Angelica’s relationship: Carter owned the pistols Hamilton carried to the duel that killed him—the same pair Hamilton’s son Philip died holding. Burr and Carter dueled in 1799, but both men survived, leaving the pistols to play their fateful place in history and the musical.

For DC Theater Arts’ complete “Summer of Hamilton” coverage, click here.