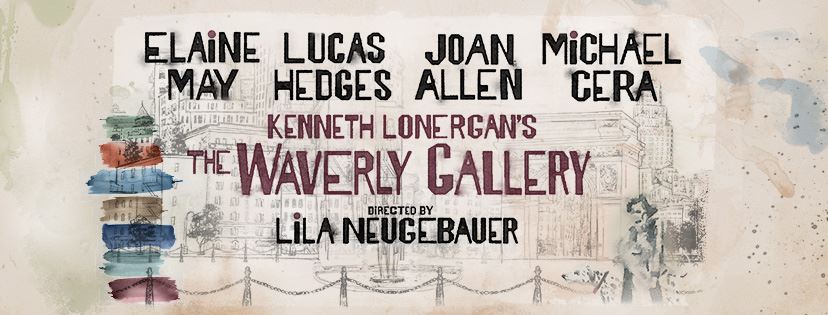

Now making its stellar Broadway debut at the Golden Theatre, The Waverly Gallery, Kenneth Lonergan’s award-nominated memory play of 1999, told from the perspective of a grandson reflecting on the growing senility and death of his grandmother, is one of those rare occurrences in art in which everything comes together perfectly and affects profoundly. It is brimming with real human experiences, emotions, and empathy, poignantly written, compellingly acted, seamlessly directed, and evocatively designed. It’s like watching the ebbing of life unfold right in front of you, but with the acuity and knowledge gained through hindsight.

As the play opens, we watch Gladys, in the eponymous Greenwich Village art gallery she’s operated for decades, yammering to a young man about some people she knew (one of the women, she reiterates, was “a nut”). She’s a bit forgetful and hard of hearing, as she tries to explain the nebulous relationships with risible long-windedness and redundancy. We’re not quite sure what their connection is, until she points out to him that her husband was his grandfather – as if he didn’t know. He is trying his best to be tolerant and reassuring, sometimes attempting to correct her faulty short-term memory (no, he doesn’t write for a newspaper, he’s a speechwriter for the EPA), as she happily rambles on. And so she does with his mother Ellen and her husband Howard in their apartment on the Upper West Side, and with Don, an aspiring artist from New England to whom she offers a show and a place to live in the back room of the gallery, until she has deteriorated to the point at which she no longer can – feeling “all mixed up” and dolefully admitting, “I don’t know what happened to me.”

In a brilliant return to the stage, Elaine May, under the superb direction of Lila Neugebauer, fully inhabits the role of Gladys, a former lawyer, activist, and socializer, as she steadily declines into increasing dementia and loneliness. Every forgotten word and clouded memory she grasps for, every facial expression, posture, and gesture she so naturally assumes, and every mental state and mood she portrays – from funny absentmindedness to full-blown panic – is precise, recognizable, and heartrending (especially for those of us who’ve had the experience of caring for elderly relatives whose faculties were failing).

Lucas Hedges is her grandson Daniel, who serves as the narrator, looking back on the last years of her life with a mixture of objectivity and sensitivity, as he confesses his frequent impatience and mishandling of her situation with newfound compassion and comprehension. His segments of direct-address narration, which are interspersed amidst the scenes of re-enactments, add immeasurably to Lonergan’s highly-personal vision of the universal theme of watching a loved one slip away and the helplessness of not knowing what to do or how to deal with it.

The well-orchestrated family dynamics are masterfully played out by Joan Allen as the short-tempered Ellen, whose anger, frustration, and inability to cope are apparent in every exasperated action and response to her mother, until she finally breaks down in tears from the overwhelming stress and responsibility, and the approaching dismal outcome. David Cromer as Howard contributes to the dysfunction, yelling too loud so Gladys can hear him and turning the conversation to Daniel’s unseen on-again off-again unrequited love interest, as they all engage in multiple conversations, with everyone talking at once, and no one, especially Gladys, truly being heard. Michael Cera rounds out the outstanding ensemble as the optimistic but unsuccessful artist Don, grateful for his unattended gallery opening, providing company, friendship, and support for Gladys, and erroneously convinced that her problems are not due to Alzheimer’s, but to a faulty hearing aid (which provides a running sight gag throughout the show).

Supporting the narrative is an effective and expressive design, with a shifting set by David Zinn that contrasts the tasteful and well-maintained apartment of Ellen and Howard with Gladys’s timeworn, dingy, and old-fashioned one, and her gallery (completely bereft of customers) hung with art that switches from mid-century abstraction to the subsequent return of realism. The advancement of time is also seen in projections by Tal Yarden that show the changing neighborhood, about which Gladys so often complains, as she, too, undergoes the inescapable transformations that come with aging.

The Waverly Gallery is funny till it’s not, and then it is devastating. You will enter Lonergan’s dramatic journey with laughter and leave wiping away the tears, and maybe, in the process, even develop a little more understanding of the challenges of growing old and become more patient with those going through it. This is theater that not only observes life, but can also make a difference.

Running Time: Approximately two hours and 10 minutes, including an intermission.

The Waverly Gallery plays through Sunday, January 27, 2019, performing at the Golden Theatre – 252 West 45th Street, NYC. For tickets, call (212) 239-6200, or purchase them online.