“When did money become the thing—the only thing?” asks an ambitious young financial journalist in her opening monologue. She then answers her own question: “The mid-eighties. 1985 to be exact…. It was like a new religion was being born.” What follows is a riveting economic epic that Playwright Akad Akhtar calls “a ritual enactment” of “the origins of debt financing”—the crafty new religion’s credit creed.

As we learn, that journalist, Judy Chen (a briskly tenacious Nancy Sun), is researching a book that if published “would torpedo every piety of this new faux-religion of finance.” So hang on tight, because this show is going to be (as they say of the market) volatile.

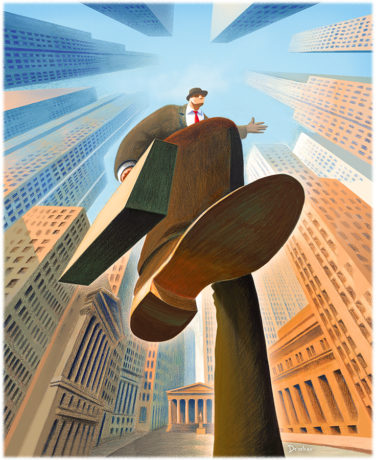

Performed in the round on the Fichhandler stage, Junk is a sleek look at the slick world of the high-rollers, wheeler-dealers, and pecuniary schemers whose machinations made fortunes and changed the course of American finance. It takes place when high-yield junk bonds came into being—new investment and buyout maneuvers that manufacture debt in order to create wealth. Making money from its absence sounds counterintuitive to folks familiar with ordinary forms of borrowing: car payments, student debt, mortgages, and the like. But Junk makes us privy to a new trade secret of the super-rich.

The protagonist of Junk is a cunning trader named Robert Merkin. “Debt is an asset,” he is quoted in a Time magazine cover story about him. Though modeled loosely on Michael Milken, the inventor of junk bonds who made billions then did time for his crimes (after which he still had billions), Merkin is not written as a money-grubbing bad guy. As played by the lanky and likable Thomas Keegan, he’s an amiable fellow, a decent family man, well-liked by his associates (though distrusted by his adversaries and competitors). To his credit he has a sensitivity to income inequality that though capitalist to its core is sincere:

MERKIN: The only real way to get rid of racial prejudice in this country is to make wealth available to everyone. Because the only thing we care about more than race in America? Is wealth.

And he is very open about what he’s up to, as he tells the inquiring journalist:

CHEN: You’re known for calling debt an asset. To a lot of people … that idea of debt having value is confusing.

MERKIN: What is debt, but the promise to pay? From that promise, everything else flows. Debt is the nothing that gives birth to everything.

CHEN: That’s very abstract.

MERKIN: Is it? What’s money? Debt on a piece of paper. That’s all a dollar bill is. The US government’s promise on paper to honor the face value of this debt.

CHEN: Right.

MERKIN: And how does the US government honor that debt?

CHEN: It sells Treasury Bonds.

MERKIN: It sells debt to honor debt. Uncle Sam sells bonds to create money. That’s what we’re doing. Selling bonds to create value.

The storyline of Junk—what Merkin is up to right now—centers on his attempt to take over a steel company that is listed on the Stock Exchange, which would be a coup for him. He intends to risk none of his own money; instead, he’ll raise funds from investors whom he’s made megawealthy, and use the steel company’s own cash flow as collateral to borrow the purchase price.

This makes the antagonist of the story the chief executive of that steel company, Thomas Everson, Jr. Played with a poignant earnestness by Edward Gero, Everson is a principled man. He has diversified the company into other profitable divisions in order to save the money-losing steel business that he inherited. The suspense in Junk’s sometimes dizzying plot is whether Merkin’s hostile takeover will succeed, which would mean he’d shut down the profit-sinkhole steel division and put 15,000 people in rural Pennsylvania out of a job.

Junk has a cast of 17, a few of whom double, so we meet a lot of characters. Remarkably, we get to know each of their stakes in the story. Here are the major ones.

Merkin’s circle of staffers and clients includes Israel Peterman, an eager corporate raider whom Merkin taps to front takeover money (played with wired vigor by Jonathan David Martin); Raul Rivera, a lawyer in Merkin’s firm (a smooth and savvy Perry Young); Murray Lefkowitz, a man for whom Merkin has made millions but who now fears to gamble (a touchingly anguished Michael Russotto); and Boris Pronsky, a man literally indebted to Merkin who proves his downfall (a curiously agitated Elan Zafir).

Everson is advised by two women: Maximilien (“Max”) Cizik, who was Everson Sr’s investment banker for twenty years (a no-nonsense Lise Bruneau) and her colleague Jacqueline Blount, a young, brainy, top-of-her-class lawyer (a briskly proficient Kashayna Johnson).

Akhtar’s script features four super-smart major women characters who are consistently respected as such. Besides the journalist Chen and Emerson’s advisers Cizik and Blount, there’s also Amy Merkin, Robert Merkin’s wife. She and he met in business school, and she’s his financial collaborator and confidant; she knows how to work the market just as well as he does, if not better. They’re teammates—in love, new parenthood, and wealth accumulation. And she is played by Shanara Gabrielle with a keen intelligence that makes their scenes together some of the most electric in the show.

Another laudable layer of Akhtar’s script is its handling of race and ethnicity. Chen is Chinese Amerian; Rivera is of Cuban extraction; Blount is African American; and Merkin, Peterson, and Cisek are Jewish. Unsettling undercurrents of prejudice surface at unexpected turns.

Among Merkin’s foils (there are several, including in law enforcement) is a man named Leo Tresler. Leo is a ridiculously rich private equity expert with a very low opinion of Merkin, as Chen learns when she interviews him for her book. As played with ingratiating entitlement by David Andrew Macdonald, Tresler makes moves on Chen that lead to a sexual payoff at her place. In another of Chen’s very share-y chats with us, she admits that it wasn’t his going down on her that got her off; it was when she fantasized about his enormous financial power.

Later Leo explains the meaning money has for men:

TRESLER: A man is a funny thing, Judy. A man is what he has…. Everybody wants to say it’s something else. Something more noble. But it’s not. What a man has is what makes him in the eyes of the world, and in his own eyes…. And the last thing a man wants to feel is that there’s another man out there who has what he doesn’t, and that the woman he might be falling in love with knows it.

The way this sexual subplot informs the main plot about a hostile takeover is mindblowing.

Akhtar’s storytelling is fluid. Scenes are over and out. The story races apace like a stock market ticker. And Jackie Maxwell directs all in an unerring uptempo.

Set Designer Misha Kachman’s utilitarian set pieces, notably bright white tables, glide in and out. Akhtar’s dialogue is rat-a-tat-tat percussive. It’s as if the playing area is a trading floor for barbs and retorts. Many scenes are phone conversations, but there’s not a phone prop in sight; Lighting Designer Jason Lyons isolates each actor in a harsh white spot and the effect is gripping. Costume Designer Judith Bowden handles the ’80s power suits and big hair with nuance and eloquence. Sound Designer Darron L West gets all the office-world noises just right; and during confidential scenes between Merkin and Pronsky in a parking garage, West creates the empty echo of their voices amazingly.

Junk is a perfectly on-point power play and a formidable achievement in dramatic and political storytelling. It offers profound insight into how the moneyed in America got us where we are. And it ends on a promissory note of iniquity and inequity to come.

Full cast (in alphabetical order):

Union Rep/Corrigan Wiley: Elliott Bales

Giuseppe Addesso: Nicholas Baroudi

Maximilien Cizik: Lise Bruneau

Kevin Walsh: JaBen Early

Charlene Stewart/Lawyer: Amanda Forstrom

Amy Merkin: Shanara Gabrielle

Thomas Everson, Jr.: Edward Gero

Mark O’Hare/Curt: Michael Glenn

Devon Atkins/Waiter: Dylan Jackson

Jacqueline Blount: Kashayna Johnson

Robert Merkin: Thomas Keegan

Leo Tresler: David Andrew Macdonald

Israel Peterman: Jonathan David Martin

Murray Lefkowitz/Maître d’/Counsel: Michael Russotto

Judy Chen: Nancy Sun

Raul Rivera: Perry Young

Boris Pronsky: Elan Zafir

Other credits

Director: Jackie Maxwell

Set Designer: Misha Kachman

Costume Designer: Judith Bowden

Lighting Designer: Jason Lyons

Sound Designer: Darron L West

Fight Director: Lewis Shaw

Dialect and Vocal Coach: Lisa Nathans

Casting Directors: Victor Vazquez and Geoff Josselson

Stage Manager: Christi B. Spann

Assistant Stage Manager: Rachael Danielle Albert

Production Assistant: Dayne Sundman

Running Time: Two hours, with no intermission.

Junk plays through May 5, 2019, at Arena Stage – 1101 Sixth Street, SW, Washington, DC. For tickets, call (202) 488-3300 or purchase online.