[CLICK HERE to read all 18 dispatches in chronological order.]

Chapter 18: The Living Moment, July 21 7pm

Returning to a theme running through prior chapters, Daisey spelled out America’s founding sins: “The fundamental elements of this nation’s history are not what we were taught. America is a grand attempt at democracy built on two pillars, genocide and slavery. We broke every treaty. We invented racism. History is written to hide what really happened.”

“Obama was not a radical revolutionary,” said Daisey. “He was dedicated to rolling back the Reagan revolution.”

“Powerful ideas tend to be radical,” Daisey said. “You need radicals. They move the center to change.” And centrism had “sapped energy from the Clinton era.” So Obama and the Democratic party were unprepared when a new radical revolution arose on the right in the form of the Tea Party.

Fox News had for 25 years been “metasticizing the culture,” Daisey said. Under Rupert Mudoch’s hire Roger Ailes, the network deliberately “exploited the myth of objective journalism.” Aisles had figured out that “people will not challenge what shows up as TV news even if it’s propaganda.” As “other networks don’t challenge” what was going on, Fox News became “the dominant force in news.”

The consequence of that dominance was to hobble the Obama presidency. “The power of Fox News and talk radio gives Republicans the idea to start primarying people”—meaning Tea Party Republicans began to replace moderate Republicans in Congress. Eventually “the Tea Party becomes absorbed into the party,” advocating for extreme tax cuts and “willing to be destructive to government itself.”

Daisey had earlier talked about how nonvoters have become the dominant party in electoral politics. Now, he said, “Republicans are becoming nihilistic like the party of apathy. They want to do something radical to damage the machine as much as possible. These are the birth pangs of a white nationalist party.”

Obama and the Democratic party did not get what was happening. They tried to collaborate across the aisle. But Obama’s “technique of calling Republicans to the table” was not going to work, because “you can’t negotiate with that nihilism.” Meanwhile “the new playbook of Republicans” was to quash everything of Obama’s they could.

Daisey ran through what came down:

Obamacare, the Affordable Care Act, barely made it out of Congress watered down, with its provision for single-payer health coverage gutted.

During the Merritt Garland Supreme Court nomination fiasco, “Obama needed to go to war” but “does not put up a fight.” Garland was as moderate a nominee as could be but Obama was was “outmaneuvered” by “the insane bad-faith sea turtle” Mitch McConnell.

Citizens United defined corporations as people, which ushered in unfettered spending of “soft dark money in elections.” Obama “waffles with al-Assad in Syria.” Under Obama there is a “massive expansion of the secrecy state,” which limits the right of the press—and which Trump will later inherit.

Finally Daisey comes to a bright spot: “Marriage equality becomes settled.” And how that happened holds a lesson: “The equation changes with the logarythmic effect,” which is when people rise up en masse until power has to accommodate.

The Black Lives Matter movement coincided with the ubiquity of phone cams. “People can now film cops abusing and killing.” The technical advance becomes “an end-run around media” at a time when “journalism is collapsing.” Today, with social media, “we are all journalists and publishers.”

Meanwhile, angry at Obama and disillusioned with government, the radical right was gaining momentum—increasingly enamored of “strongman leaders, fascism, and white nationalism” and “gerrymandering” its way to minority rule. “They are rotting out democracy from inside.”

And then Daisey pivoted from the past to the future with a dire prediction: “White nationalism has consumed the Republican party. The system that allows Trump to take root will outlast him. Getting rid of Trump will not save you. There will be someone after him who is smarter, who will play the same angle. Looking at the arc of history tells why this moment is important. If there isn’t a cultural balance to fascism, we will fail.”

Still looking to the future, Daisey returned to the topic of the climate in the context of a record-breaking heat wave. “There’s not much time left. The earth is burning. People are now scared of the heat.” Daisey has read the entire 11,000-page IPCC report, which has already eliminated a best-case scenario and warned of next-worsts. If “a catastrophic runaway greenhouse effect” occurs, nothing we do can reverse it. Our “cognitive dissonance”—which has already prevented acknowledgement of the nation’s “racism, sexism, and classism”—now keeps us oblivious to “the end of this world.”

Then Daisey wrapped together what has been happening historically in American politics and the ahistorical climatic event we now face. “When temperatures break at the equator, those people will go north and south to survive.” It will be “the the largest migration in human history” with “millions of people flooding here.” When that happens, Daisey said, “authoritarianism will be the order of the day.”

Daisey spoke personally of the meaning Howard Zinn has had for him, likening Zinn to the grandfather he wishes he had. And Daisey read a passage from the last revision of Zinn’s book where he explains why he wrote it. The line that seemed to connect directly to Daisey was this: “I had no illusions about ‘objectivity,’ if that meant avoiding a point of view.”

To that point Daisey quoted himself, a passage that he once spoke aloud during a monologue and a journalist recorded and reported:

Before we go any further, I wanted to tell you—just this once—that I am an unreliable narrator. I am made of dust and shadows. I am telling you things now, and I will tell you more things. You will never know my secret heart. You will think you hold it in your hand, that you know the depths of me. And you know nothing. You will never know me. And I never wanted you to. That’s not why we’re here. That’s not why we ever came here to this place. And you should know the truth: That there are no reliable narrators.

Daisey did indeed let us know something of his secret heart in the final moments when he disclosed the personal reason he did this show. It’s his story to tell, on stage or to friends in life as he wishes, so to put its specifics on the record would seem a spoiler and breach of confidence. In broad outline, though, it was a very moving story about performing a self he knew himself not to be—and what drew him to create this 18-chapter A People’s History was that America too presents a face to the world that is belied by who it really is.

“I wanted to put my arms around history,” Daisey said. “I wanted to find out if change is possible.”

One could sense in Daisey’s intense candor at the end a burning hope for radical recovery—for himself, for our nation, and for the earth.

Chapter 17: The Chimes At Midnight, July 20 8pm

Its code name was Operation Paperclip.

At the end of World War II the U.S. secretly extracted more than 1,600 scientists and engineers from Germany and brought them here to develop America’s rocket program, which led to, among other things, ICBMs and the Apollo. Many were Nazis, including Wernher von Braun, known as the father of modern rocketry.

“The moon project is possible because we worked with Nazis,” observed Daisey. “Nazis put our asses on the moon.

“Is there a more vibrant sign of white supremacy?,” Daisey wondered.

“Power doesn’t care” if it compromises ideals, he said. “What power needs to do is erase resistance.”

Daisey also commented on the oppressive heat wave we are in. “It’s hot because we’re fucked,” he said. “The world as you know it is ending.” The latest IPPC report—all of which Daisey has read—is “a death warrant.” The scenario that global temperatures will rise 1.5 degrees is no longer tenable. It’s going to be 2 degrees minimum, maybe more. Every degree increase in temperature doubles how much water the atmosphere can hold—hence the day recently when a month’s rain fell in one hour. “The environment is out of balance. There’s not going to be balance again.”

A climate catastrophe is coming, “the straw initiative” won’t stem it, and we are not paying attention because “we are very good at not looking at ourselves.” We are in denial about the climate catastrophe in the same way we are in denial about the nation’s foundational history in genocide and slavery. Meanwhile “the president and a whole party are full-blown racists and fascists.”

“A liberal,” Daisey said, “is someone who has the best ideas about what needs to be done as long as sacrifice is not required.”

Then Daisey picked up the history of America according to Zinn where the last chapter left off:

It was clear as Clinton ended his two-term presidency … that the Democratic candidate for president would now be the man who served him faithfully as Vice President, Albert Gore. The Republican Party chose as its candidate for President the Governor of Texas, George W. Bush, Jr. known for his connection to oil interests and the record number of executions of prisoners during his term in office.

Although Bush, during the campaign, accused Gore of appealing to “class warfare,” the candidacy of Gore and his Vice President, Senator Joseph Lieberman, posed no threat to the superrich. A front-page story in the New York Times was headlined “As a Senator, Lieberman Is Proudly Pro-Business”…

Gore’s tactic of capturing conservative voters continued what Clinton had begun, though Gore was in an awkward dilemma: he had to run on Clinton’s record and distance himself from Clinton at the same time. The campaign messaging about a Gore presidency, Daisey joked, had to be “Like it used to be only better, and with less penises.”

The degree of difference in the corporate support of the two presidential candidates can be measured by the $220 million raised by the Bush campaign and the $170 million raised by the Gore campaign. Neither Gore nor Bush had a plan for free national health care, for extensive low-cost housing, for dramatic changes in environmental controls. Both supported the death penalty and the growth of prisons. Both favored a large military establishment, the continued use of land mines, and the use of sanctions against the people of Cuba and Iraq.

Without the existence of small donations that we have today, Daisey noted, leftist ideas and candidates had no chance. People now making micro-donations are a sign of health for accountability.

It was predictable, given the unity of both major parties around class issues…, that half the country, mostly at lower-income levels, and unenthusiastic about either major party, would not even vote.

A journalist spoke to a cashier at a filling station, wife of a construction worker, who told him: “I don’t think they think about people like us. . . . Maybe if they lived in a two-bedroom trailer, it would be different.” An African American woman, a manager at McDonald’s, who made slightly more than the minimum wage of $5.15 an hour, said about Bush and Gore: “I don’t even pay attention to those two, and all my friends say the same. My life won’t change.”

Daisey reiterated that the electoral college was installed to protect slavery, “to prevent too much democracy,” and “there was ample time to get rid of it.” But on that election night in Florida, the electoral college produced a tense standstill.

Bush had this advantage: his brother Jeb Bush was governor of Florida, and the secretary of state in Florida, Katherine Harris, a Republican, had the power to certify who had more votes and had won the election. Facing claims of tainted ballots, Harris rushed through a partial recounting that left Bush ahead.

An appeal to the Florida Supreme Court, dominated by Democrats, resulted in the Court ordering Harris not to certify a winner and for recounting to continue. Harris set a deadline for recounting, and while there were still thousands of disputed ballots, she went ahead and certified that Bush was the winner by 537 votes. This was certainly the closest call in the history of presidential elections. With Gore ready to challenge the certification, and ask that recounting continue, as the Florida Supreme Court had ruled, the Republican Party took the case to the U.S. Supreme Court.

“The Supreme Court loves states rights,” said Daisey. “In normal times they would not even have taken the case.” But these were not normal times.

The Supreme Court split along ideological lines. The five conservative judges (Rehnquist, Scalia, Thomas, Kennedy, O’Connor) … overruled the Florida Supreme Court and prohibited any more counting of ballots. They said the recounting violated the constitutional requirement for “equal protection of the laws” because there were different standards in different counties of Florida for counting ballots.

“So what, they had different numerical systems?” Daisey joked. “Some with an abacus, some with imaginary numbers?”

The four liberal judges (Stevens, Ginsburg, Breyer, Souter) argued that the Court did not have the right to interfere with the Florida Supreme Court’s interpretation of state law. Breyer and Souter argued even if there was a failure to have a uniform standard in counting, the remedy was to let there be a new election in Florida with a uniform standard.

The fact that the Supreme Court refused to allow any reconsideration of the election meant that it was determined to see that its favorite candidate, Bush, would be President. Justice Stevens pointed this out, with some bitterness, in his minority report: “Although we may never know with complete certainty the identity of the winner of this year’s presidential election, the identity of the loser is perfectly clear. It is the nation’s confidence in the judge as an impartial guardian of the rule of law.”

“This was when democracy got fucked,” said Daisey. It was “a major breaking point. Five motherfuckers committed an administrative coup in bad faith.”

Bush, taking office, proceeded to pursue his pro-big-business agenda with total confidence, as if he had the overwhelming approval of the nation….He pushed tax cuts for the wealthy, opposed strict environmental regulations that would cost money for the business interests, and planned to “privatize” Social Security by having the retirement funds of citizens depend on the stock market.

Then 9/11 happened.

Daisey began the story personally, with his own traumatizing memories of fleeing on foot from the cataclysm in Lower Manhattan in order to make it across the Brookyn Bridge, then turning and watching behind him as the towers fell.

It was an unprecedented assault against enormous symbols of American wealth and power, undertaken by 19 men from the Middle East, most of them from Saudi Arabia. They were willing to die in order to deliver a deadly blow against what they clearly saw as their enemy, a superpower that had thought itself invulnerable.

“The world was on our side then,” Daisey said. We and the world could have “come together in pain. Instead terrorism was turned into a tool for power to get what it wanted.”

President Bush immediately declared a “war on terrorism” and proclaimed: “We shall make no distinction between terrorists and countries that harbor terrorists.” Congress rushed to pass resolutions giving Bush the power to proceed with military action, without the declaration of war that the Constitution required. The resolution passed unanimously in the Senate, and in the House of Representatives only one member dissented — Barbara Lee, an African American from California.

“Terrorism is still being used to justify U.S. military actions. Since then we have never not been in a war in this century,” said Daisey. And there isn’t the same popular impetus to protest America’s war-making as there was when there was a draft.

It should have been obvious to Bush and his advisers that terrorism could not be defeated by force. The historical evidence was easily available. The British had reacted to terrorist acts by the Irish Republican Army with military action again and again, only to face even more terrorism. The Israelis, for decades, had responded to Palestinian terrorism with military strikes, which only resulted in more Palestinian bombings. Bill Clinton, after the attack on U.S. embassies in Tanzania and Kenya in 1998, had bombed Afghanistan and the Sudan. Clearly, looking at September 11, this had not stopped terrorism

“Terrorism,” said Daisey, “is a figleaf to give an open authorization to do whatever power wants.”

Furthermore, the months of bombings had been devastating to a country that had gone through decades of civil war and destruction. The Pentagon claimed that it was only bombing “military targets,” that the killing of civilians was “unfortunate … an accident . . . regrettable.” However, according to human rights groups and accumulated stories in the American and West European press, at least 1,000 and perhaps 4,000 Afghan civilians were killed by American bombs.

This, said Daisey, is white supremacy thinking “brown people are not worth shit.”

Suddenly overcome with emotion, Daisey recalled his own fury at the time, the trauma of being near ground zero that now expressed itself in rage. The fun he was having at the beginning had turned to remembered pain.

Mostly the media were all on board.

The head of the television network CNN, Walter Isaacson, sent a memo to his staff saying that images of civilian casualties should be accompanied with an explanation that this was retaliation for the harboring of terrorists. “It seems perverse to focus too much on the casualties or hardships in Afghanistan,” he said. The television anchorman Dan Rather declared: “George Bush is the President. . . . Wherever he wants me to line up, just tell me where.”

The United States government went to great lengths to control the flow of information from Afghanistan. It bombed the building housing the largest television station in the Middle East, Al- Jazeera, and bought up a satellite organization that was taking photos showing the results, on the ground, of the bombing.

Mass circulation magazines fostered an atmosphere of revenge. In Time magazine, one of its writers, under the headline “The Case for Rage and Retribution,” called for a policy of “focused brutality.” A popular television commentator, Bill O’Reilly, called on the United States to “bomb the Afghan infrastructure to rubble — the airport, the power plants, their water facilities, and the roads.”

This was “war advocacy for genocide,” said Daisey. “We will need to kill 100,000 people to avenge what a couple brown guys did.”

Congress passed the “USA Patriot Act,” which gave the Department of Justice the power to detain noncitizens simply on suspicion, without charges, without the procedural rights provided in the Constitution. It said the Secretary of State could designate any group as “terrorist,” and any person who was a member of or raised funds for such an organization could be arrested and held until deported.

“If you call something terrorist, you can do anything,” said Daisey. Largely “the tools are used against people of color” and always “to prove a point about our masculinity.”

The second Iraq war was waged on the pretext that there were weapons of mass destruction there—because “we want to do imperialism but with plausible deniability”—but no such weapons were ever found.

The day Daisey learned that disclosure hit him hard. Still feeling the trauma of 9/11, he “felt fractured” by what “my own government had done,” he said. “That’s the day I became radicalized.”

After killing 1.1 million Iraqis to avenge 3,500 Americans lost on 9/11, “we pulled out, abandoned them, leaving that nation splintered,” having prepared the way for when “ISIS will rise up.”

Daisey attributed the government’s failed response after Hurricane Katrina to the same indifference. “In Puerto Rico, it was even more bluntly racist.”

Touching mordantly on the financial housing crash, he said, “Who knew then that unregulated greed would lead to chaos?”

“There’s no savior coming,” Daisey said. “We have heard the chimes at midnight—meaning the hour of death. Time is short. Maybe by listening to voices of actual people we can find a way forward.”

Chapter 16: The Limits Of Imagination, July 19 8pm

The chapter title refers to the fact that “our capacity to hope is dependent on our ability to imagine something different.” And he gave two examples of how imagination boundaried what people thought was possible: the time black political leaders considered Bill Clinton “the first black president—never imagining there would ever actually be a black president” and the time the gay community never imaged same-sex marriage would be legal.

The “power of the logarithmic wave”—when people rise up and act—”can upend things we don’t expect to change,” said Daisey. What else is it, he wondered, “we don’t see that’s not far away?”

In his youth Daisey “was a big fan” of Bill Clinton “after the Reagan/Bush 12-year hegemony of bullshit,” and Daisey campaigned for “the man from Hope.” But those whom Daisey has called “the party of apathy” were unmoved. “There were more people not voting than voting.” From Zinn:

Clinton had barely won election both times. In 1992, with 45 percent of the voting population staying away from the polls, he only received 43 percent of the votes, the senior Bush getting 38 percent, while 19 percent of the voters showed their distaste for both parties by voting for a third- party candidate, Ross Perot. In 1996, with half the population not voting, Clinton won 49 percent of the votes against a lackluster Republican candidate, Robert Dole.

Perot, a wild-card disruptor and a billionaire, was ahead of his time, as witness the president today. And Dole, said Daisey, was a vestige of “old Republicanism” from before Republicans began “race-bating to win elections.”

There was a distinct absence of voter enthusiasm. One bumper sticker read: “If God had intended us to vote, he would have given us candidates.”

Daisey cited again the fact that when all Americans are polled (not just registered or likely voters), the idea of a universal heath care system has a 75 percent approval rating. But the idea has no traction in Congress. From Zinn:

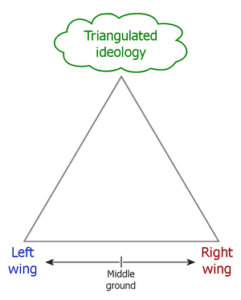

Despite his lofty rhetoric, Clinton showed, in his eight years in office, that he, like other politicians, was more interested in electoral victory than in social change. To get more votes, he decided he must move the party closer to the center. This meant doing just enough for blacks, women, and working people to keep their support, while trying to win over white conservative voters with a program of toughness on crime, stern measures on welfare, and a strong military.

He showed the same timidity in the two appointments he made to the Supreme Court, making sure that Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Stephen Breyer would be moderate enough to be acceptable to Republicans as well as to Democrats. He was not willing to fight for a strong liberal to follow in the footsteps of Thurgood Marshall or William Brennan, who had recently left the Court. Breyer and Ginsburg both defended the constitutionality of capital punishment, and upheld drastic restrictions on the use of habeas corpus. Both voted with the most conservative judges on the Court to uphold the “constitutional right” of Boston’s St. Patrick’s Day parade organizers to exclude gay marchers.

In this period “the Democratic Party transforms itself into party of big business,” and its message to labor unions, people of color, and women was: you have no option but to stay on board with us. Meanwhile Clinton kept showing off his toughness for the Republican base:

Running for President in 1992 while still Governor of Arkansas, he flew back to Arkansas to oversee the execution of a mentally retarded man on death row.

…

The “Crime Bill” of 1996, which both Republicans and Democrats in Congress voted for overwhelmingly, and which Clinton endorsed with enthusiasm, dealt with the problem of crime by emphasizing punishment, not prevention. It extended the death penalty to a whole range of criminal offenses, and provided $8 billion for the building of new prisons.

As Clinton “doubles down on punishment to look tough to the Republican base,” this crime bill “starts to energize the idea of private prisons.” The bill’s harsher sentencing adds 1 million to the total of incarcerated individuals. And yet when violent crime goes down, the prison population increases, a trend “fueled by racism.” In the words of a criminologist quoted by Zinn:

“About 70 percent of prisoners in New York State come from eight neighborhoods in New York City. These neighborhoods suffer profound poverty, exclusion, marginalization, and despair. All these things nourish crime.”

“The crime bill is not about rehabilitating neighborhoods.”

In this period, Daisey said, Clinton also threw people off welfare rolls and made them seek jobs that were not to be found. “The social safety net frays and vanishes.” Clinton’s “centrist coalition to dominate politics” has a downside that still impacts us today: “The Democratic party becomes diffuse, loses what it stands for. And as Democrats occupy the center, the other party moves toward the radical right.”

The Soviet Union falls in early 1990 and the cold war ends. This means the U.S. doesn’t have a super power to oppose, and its postwar pretext for increasing military spending is gone. Clinton’s response is to diminish the military slightly but sell munitions abroad. Daisey quoted from Zinn a newspaper report:

Next year [1995], for the first time, the United States will produce more combat planes for foreign air forces than for the Pentagon, highlighting America^ replacement of the Soviet Union as the world’s main arms supplier. Encouraged by the Clinton administration, the defense industry last year had its best export year ever, having sold $32 billion worth of weapons overseas, more than twice the 1992 total of $15 billion.

In arming the world during the Clinton presidency, said Daisey, “we created another Vietnam.”

Daisey then touched on catastrophic military policies in Somalia (where, a journalist reported, “American and UN officers made clear that numbers of Somali dead did not interest them, and they kept no count”) and Rwanda (“where famine and murderous tribal warfare were ignored”).

There was a UN force in Rwanda that might have saved tens of thousands of lives, but the United States insisted that it be cut back to a skeleton force. The result was genocide — at least a million Rwandans died. As Richard Heaps, a consultant to the Ford Foundation on Africa wrote to the New York Times : “The Clinton administration took the lead in opposing international action.”

When, shortly after, the Clinton administration did intervene with military force in Bosnia, journalist Scott Peterson…commented on the difference in reactions to genocide in Africa and in Europe. He said that it was “as if a decision had been made, somewhere, that Africa and Africans were not worth justice.”

In the mid-1990s, Daisy said, a politics arose known as neoliberalism: “the idea that we can seem to keep our values but we no longer believe the government can really solve problems.” It was, said Daisy, “apathy made policy.”

Internationally, the U.S. secured “a control network” that Daisey termed “new colonialism”:

The World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, both dominated by the United States, adopted a hard-nosed banker’s approach to debt-ridden Third World countries. They insisted that these poor nations allocate a good part of their meager resources to repaying their loans to the rich countries, at the cost of cutting social services to their already-desperate populations.

And with globalism, “we made a decision that we didn’t care about protecting American jobs.”

According to the business magazine Forbes, the 400 richest families owned $92 billion in 1982, but thirteen years later this had jumped to $480 billion. In the nineties, the wealth of the 500 corporations of the Standard and Poor’s Index had increased by 335 percent. The Dow Jones average of stock prices had gone up 400 percent between 1980 and 1995, while the average wage of workers had declined in purchasing power by 15 percent.

“There is no equality here, no reckoning,” said Daisey. “This is the Clinton legacy.”

Then the chapter took a turn that left the audience stunned in silence. Reading from a 2017 article in The Atlantic by Caitlin Flanagan, Daisey said:

Yet let us not forget the sex crimes of which the younger, stronger Bill Clinton was very credibly accused in the 1990s. Juanita Broaddrick reported that when she was a volunteer on one of his gubernatorial campaigns, she had arranged to meet him in a hotel coffee shop. At the last minute, he had changed the location to her room in the hotel, where she says he very violently raped her. She said that she fought against Clinton throughout a rape that left her bloodied. At a different Arkansas hotel, he caught sight of a minor state employee named Paula Jones, and, Jones said, he sent a couple of state troopers to invite her to his suite, where he exposed his penis to her and told her to kiss it. Kathleen Willey said that she met him in the Oval Office for personal and professional advice and that he groped her, rubbed his erect penis on her, and pushed her hand to his crotch.

“I heard these accounts then,” Daisey said. “I thought they were slutty opportunists. But we just had a revolution about this two years ago, #MeToo.” Daisey now believes the women.

“If you don’t actively stand for the sovereignty of women, these are things that can happen. He treated women this way. He pursued policies that got us where we are.”

Later that night, Daisey tweeted:

There’s a moment near the end of tonight’s show, when I was reading an account of three sexual assault allegations against Bill Clinton that the air turns to glass—cold, hard, quiet, and crystalline. You can feel people assessing their choices and their biases.

Chapter 15: The Tyranny Of Wisdom, July 18 8pm

The title refers to the tyranny of conventional wisdom, which holds that no one person can make a difference, real change isn’t possible, yada yada. “Journalists are stewards of such conventional wisdom.” It is often “the objective voice of authority,” meaning “straight white men.”

“Yes, he’s racist!” Daisey shouted, as if so CNN could hear. “If the president and an entire party are racist, that’s a lot of people. Maybe it means…we’re a racist country.”

Recapping a main theme of A People’s History, Daisey spoke of America’s “two foundational sins,” genocide and slavery, “the beating heart of American exceptionalism.” And his audience was not off the hook. “We are all in this shit together. We are up to our necks in blood.”

Tonight was the 1980s, “a time of universal greed,” and throughout the chapter Daisey introduced exemplary stories of individuals who took direct action for change—”rebels and revolutionaries” who were part of “an unrepentant resistance that runs through this period.” He read from Zinn:

In September of that year [1980], Philip Berrigan, his brother Daniel (the Jesuit priest and poet), Molly Rush (a mother of six), Anne Montgomery (a nun and counselor to young runaways and prostitutes in Manhattan), and four of their friends made their way past a guard in the General Electric Plant at King of Prussia, Pennsylvania, where nose cones for nuclear missiles were manufactured. They used sledgehammers to smash two of the nose cones and smeared their own blood over missile parts, blueprints, and furniture. Arrested, sentenced to years in prison, they said they were trying to set an example to do as the Bible suggested, to beat swords into plowshares.

“You can’t know whether what you do will be a movement or laughed at,” said Daisey, a point made back then by Daniel Berrigan:

I know of no sure way of predicting where things will go from there, whether others will hear and respond, or how quickly or slowly. Or whether the act will fail to vitalize others, will come to a grinding halt then and there, its actors stigmatized or dismissed as fools. One swallows dry and takes a chance.

“You have to be informed by your own moral conscience,” said Daisey, now clearly nudging his audience toward becoming citizen activists themselves. “Conventional wisdom can change. If enough people do something, it becomes conventional wisdom.”

At a time when the nation was pouring money into weapons that could exterminate the human race, many people said no. From Zinn:

On June 12, 1982, the largest political demonstration in the history of the country took place in Central Park, New York City. Close to a million people gathered to express their determination to bring an end to the arms race.

Berrigan, after serving his jail term, went and did it again. He went back to the plant in King of Prussa, bled over everything, then was sent back to prison.

“Why don’t we do something like that?” Daisey asked not rhetorically. “We are the best people—who get to do nothing.”

Daisey cited an instance of conventional wisdom shifting:

In less than three years, there had come about a remarkable change in public opinion. At the time of Reagan’s election, nationalist feeling — drummed up by the recent hostage crisis in Iran and by the Russian invasion of Afghanistan — was strong; the University of Chicago’s National Opinion Research Center found that only 12 percent of those it polled thought too much was being spent on arms. But when it took another poll in the spring of 1982, that figure rose to 32 percent. And in the spring of 1983, a New York Times/CBS News poll found that the figure had risen again, to 48 percent.

Today, said Daisey, there are issues that have approval ratings of 75 percent to 80 percent, including medicare for all and taking money from weaponry to fund eduction. Yet no matter which party controls Congress, that people’s voice has not been taken seriously.

Meanwhile, “the world is burning, and there isn’t time.” Referring to the day last week when a month of rain fell on the DMV in one hour, he said, “Your weather is already broken.” Half the carbon now in the atmosphere was emitted since 1994; “half the damage is from then to now.” If the coming greenhouse catastrophe is to be prevented, according to the IPPC, it has to be done within 12 years. “We use the same tools to not look at it” that we use not to to acknowledge America’s founding crimes.

“It’s going to be us,” he said. “How are we going to be accountable? What if you dared to do something?”

Daisey returned to his theme that the Democratic and Republican parties are both outnumbered by “the party of apathy and nihilism”—50-plus percent who “literally don’t believe in America.” From Zinn:

Because our peculiar voting arrangements allow a small margin of popular votes to become a huge majority of electoral votes, the media can talk about “overwhelming victory,” thus deceiving their readers and disheartening those who don’t look closely at the statistics. Could one say from these figures that “the American people” wanted Reagan, or Bush, as President? One could certainly say that more voters preferred the Republican candidates to their opponents. But even more seemed to want neither candidate. Nevertheless, on the basis of these slim electoral pluralities, Reagan and Bush would claim that “the people” had spoken.

Daisey noted that during this time Democrats controlled Congress, and they could well have eliminated the Electoral College but didn’t—so it “bit us in the ass” in 2016.

Daisey touched swiftly on the Iran-contra affair as “a lens into how we shape scandal” and to make a point about how “when your government gaslights, you it’s authoritarianism.” From Zinn:

The whole Iran-contra affair became a perfect example of the double line of defense of the American Establishment. The first defense is to deny the truth. If exposed, the second defense is to investigate, but not too much; the press will publicize, but they will not get to the heart of the matter.

…

The limits of Democratic party criticism of the affair were revealed by a leading Democrat, Senator Sam Nunn of Georgia, who, as the investigation was getting under way, said: “We must, all of us, help the President restore his credibility in foreign affairs.”

Also during this period “Roger Ailes comes to power” and remakes Fox News to mimic the other networks—because “if you control the frame, you control everything.” It was a media manipulation that was to “erode belief in an objective worldview and the sense there was any objectivity.”

The year 1992 marked the 500th anniversary of Columbus’s instigation of the invasion of Native land. And no longer, Daisey noted, is Columbus Day revered as it had been.

The largest ecumenical body in the United States, the National Council of Churches, called on Christians to refrain from celebrating the Columbus quincentennial, saying, “What represented newness of freedom, hope and opportunity for some was the occasion for oppression, degradation and genocide for others.”

“It was time when churches stood up against fascism,” said Daisey, in implicit contrast to Evangelicals’ enabling of it today.

The National Endowment for the Humanities funded a traveling exhibition called “First Encounter,” which romanticized the Columbus conquest. When the exhibition opened at the Florida Museum of National History, Michelle Diamond, a freshman at the University of Florida, climbed aboard a replica of one of Columbus’s ships with a sign reading “Exhibit Teaches Racism.” She said: “It’s a human issue — not just a Red [Indian] issue.” She was arrested and charged with trespassing, but demonstrations continued for sixteen days against the exhibit.

“God bless that woman,” said Daisey. “If most of us protested this way, things would change. Power can’t stand against that.”

The publication Rethinking Schools, which represented socially conscious schoolteachers all over the country, printed a 100-page book called Rethinking Columbus, featuring articles by Native Americans and others, a critical review of children’s books on Columbus, a listing of resources for people wanting more information on Columbus, and more reading material on counter-quincentenary activities. In a few months, 200,000 copies of the book were sold.

A Portland, Oregon, teacher named Bill Bigelow, who helped put together Rethinking Schools, took a year off from his regular job to tour the country in 1992, giving workshops to other teachers, so that they could begin to tell those truths about the Columbus experience that were omitted from the traditional books and class curricula.

“You can be Bill Bigelow,” said Daisey. “Direct action is how change happens.”

Bringing this message home, Daisey quoted from the original ending of Zinn’s book:

The prospect is for times of turmoil, struggle, but also inspiration. There is a chance that such a movement could succeed in doing what the system itself has never done — bring about great change with little violence. This is possible because the more of the 99 percent that begin to see themselves as sharing needs, the more the guards and the prisoners see their common interest, the more the Establishment becomes isolated, ineffectual. The elite’s weapons, money, control of information would be useless in the face of a determined population. The servants of the system would refuse to work to continue the old, deadly order, and would begin using their time, their space — the very things given them by the system to keep them quiet — to dismantle that system while creating a new one.

“The guards of the system finally realize that they have to turn against it,” said Daisy. “You are the guards.”

The prisoners of the system will continue to rebel, as before, in ways that cannot be foreseen, at times that cannot be predicted. The new fact of our era is the chance that they may be joined by the guards. We readers and writers of books have been, for the most part, among the guards. If we understand that, and act on it, not only will life be more satisfying, right off, but our grandchildren, or our great grandchildren, might possibly see a different and marvelous world.

“I don’t know if that’s true, but God I hope that it is.”

Chapter 14: The Happy Ending, July 16 8pm

“Americans don’t understand performance,” Daisey said, introducing the evening. It’s a theme Daisey developed in his monologue The Trump Card, when he dissected the ominous performative aspect of the then long-shot candidate. “Social media is a performative art form.” And Trump has mastered the art in a way that far surpasses “the racist dog-whistling” that the Republican party has been doing for years. Ever since Trump “rode down the gold escalator” and “called Mexicans rapists,” racism has been the fundamental bond with his base.

But this time, with his tweet attack on four congresswomen of color, Trump really “pulled his hood off.” There was “shock but no surprise.” This is who he is and has been. And something “tipped” in the last 24 hours. Journalists are now actually calling Trump racist. (The House resolution to say so too was being debated as Daisey spoke.)

Calling Trump “openly racist,” “a narcissist,” “a psychotic demagogue,” and more, Daisey said we can expect that Trump has “more hoods to pull off”—because for Trump’s supporters, “his white supremacy is a feature not a bug.”

“Trump loves dictators because he is a dictator”; he wants his job go be like theirs.

Getting personal, Daisey addressed the half of his audience “who know what it’s like to be with an abuser. He will lie; he will manipulate.” Trump is “the embodiment of white male rage.”

“When the shit gets this bad,” said Daisey, “I’m like, impeach the motherfucker.” At which point half the house broke into applause.

[Chapter 1 is now available in full on YouTube.]

“The largest and most powerful political party in America is apathy,” said Daisy, back on plan. About 26 percent are Democrat; 24 percent are Republican; 50 percent don’t vote. “The high water mark” for voter participation in a presidential election was 1960, said Daisey, citing Zinn:

In 1960, 63 percent of those eligible to vote voted in the presidential election. By 1976, this figure had dropped to 53 percent. In a CBS News and New York Times survey, over half of the respondents said that public officials didn’t care about people like them. A typical response came from a plumber: “The President of the United States isn’t going to solve our problems. The problems are too big.”

“Apathy is sensible,” Daisey said. “People check out of the system because system doesn’t give a shit about what they want.” That’s on top of the “anger” and “disillusionment” left in the wake of Vietnam and Watergate, when Nixon “tried to suborn the system.” During the 2016 presidential campaign, Trump’s communications with Russia seeking dirt on Hillary turned into “Dumb Watergate—the same errors only stupider.”

Jimmy Carter, next up in Daisey’s plan, seemed “super nice” and was “good at performing who we wanted.” From Zinn:

His appeal was “populist”—that is, he appealed to various elements of American society who saw themselves beleaguered by the powerful and wealthy. Although he himself was a millionaire peanut grower, he presented himself as an ordinary American farmer. Although he had been a supporter of the Vietnam war until its end, he presented himself as a sympathizer with those who had been against the war, and he appealed to many of the young rebels of the sixties by his promise to cut the military budget.

But Carter’s international record was actually not nice.

Under Carter, the United States continued to support, all over the world, regimes that engaged in imprisonment of dissenters, torture, and mass murder: in the Philippines, in Iran, in Nicaragua, and in Indonesia, where the inhabitants of East Timor were being annihilated in a campaign bordering on genocide….

Once elected, Carter declined to give aid to Vietnam for reconstruction, despite the fact that the land been devastated by American bombing. Asked about this at a press conference, Carter replied that there was no special obligation on the United States to do this because “the destruction was mutual.”

And domestically, Carter was just as bad.

Unemployment remained officially at 6 or 8 percent; unofficially, the rates were higher. For certain key groups in the population — young people, and especially young black people — the unemployment rate was 20 or 30 percent.

It soon became clear that blacks in the United States, the group most in support of Carter for President, were bitterly disappointed with his policies. He opposed federal aid to poor people who needed abortions, and when it was pointed out to him that this was unfair, because rich women could get abortions with ease, he replied: “Well, as you know, there are many things in life that are not fair, that wealthy people can afford and poor people cannot.”

As Daisey has done in every chapter, he restated his major theme: the foundational pillars of America, genocide and slavery, and again this evening the residue of both came into sharp relief.

“I am compelled by laws of history to talk about Ronald fucking Reagan,” Daisey said mock seriously. Reagan won the presidency with just 26 percent of the vote and the press treated it as a landslide, the “Reagan Revolution.” From Zinn:

Unemployment grew in the Reagan years. In the year 1982, 30 million people were unemployed all or part of the year. One result was that over 16 million Americans lost medical insurance, which was often tied to holding a job.

The racism and white supremacy of the Republican party was coming more to the fore and Democrats were on board with it.

Democrats often joined Republicans in denouncing welfare programs. Presumably, this was done to gain political support from a middle-class public that believed they were paying taxes to support teenage mothers and people they thought too lazy to work. Much of the public did not know, and were not informed by either political leaders or the media, that welfare took a tiny part of the taxes, and military spending took a huge chunk of it. Yet, the public’s attitude on welfare was different from that of the two major parties. It seemed that the constant attacks on welfare by politicians, reported endlessly in the press and on television, did not succeed in eradicating a fundamental generosity felt by most Americans.

A New York Times /CBS News poll conducted in early 1992 showed that public opinion on

welfare changed depending on how the question was worded. If the word “welfare” was used, 44 percent of those questioned said too much was being spent on welfare (while 50 percent said either that the right amount was being spent, or that too little was being spent. But when the question was about “assistance to the poor,” only 13 percent thought too much was being spent, and 64 percent thought too little was being spent.This suggested that both parties were trying to manufacture an antihuman-needs mood by constant derogatory use of the word “welfare,” and then to claim they were acting in response to public opinion.

Unsurprisingly, the loyalty of both parties to capitalism was operative during this period.

The Democrats as well as the Republicans had strong connections to wealthy corporations. Kevin Phillips, a Republican analyst of national politics, wrote in 1990 that the Democratic Party was “history’s second-most enthusiastic capitalist party.”

The Reagan administration, with the help of Democrats in Congress, lowered the tax rate on the very rich to 50 percent and in 1986 a coalition of Republicans and Democrats sponsored another “tax reform” bill that lowered the top rate to 28 percent. Barlett and Steele noted that a schoolteacher, a factory worker, and a billionaire could all pay 28 percent. The idea of a “progressive” income in which the rich paid at higher rates than everyone else was now almost dead.

Daisey recalled protesting the Iraq war as a middle schooler, wearing a black arm band, and being beaten for it by other boys in the bathroom who called him names. “People would spit on me,” he said.

The end of the Iraq war turned out to be the happy ending promised in this chapter’s facetious title.

President George Bush was satisfied. As the war ended, he declared on a radio broadcast: “The specter of Vietnam has been buried forever in the desert sands of the Arabian peninsula.”The Establishment press very much agreed. The two leading news magazines, Time and Newsweek, had special editions hailing the victory in the war, noting there had been only a few hundred American casualties, without any mention of Iraqi casualties. A New York Times editorial (March 30,m1991) said: “America’s victory in the Persian Gulf war . . . provided special vindication for the U.S. Army, which brilliantly exploited its firepower and mobility and in the process erased memories of its grievous difficulties in Vietnam.”

“Now we get our manhood back,” said Daisey. But…

A black poet in Berkeley, California, June Jordan, had a different view: “I suggest to you it’s a hit the same way that crack is, and it doesn’t last long.”

Chapter 13: The Problem That Has No Name, July 14 8pm

In the present chapter—its title borrowed from Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique—Daisey spoke of three revolutions that “exploded out of the culture” following on the Civil Rights Movement. What interconnects them is that each expanded the meaning of sovereignty for all people “treated less than human.”

This candor was evident as he touched on landmarks in the second-wave women’s movement. He acknowledged he did not know the problems women face directly and was not telling women in the audience anything they did not know. He was trying to reach men.

He began with a quote from Friedan that resonated with huge numbers of women who like herself were middle-class housewives who lived in suburbs formed by ’50s white flight.

The problem lay buried, unspoken for many years in the minds of American women. It was a strange stirring, a sense of dissatisfaction, a yearning that women suffered in the middle of the twentieth century in the United States. Each suburban wife struggled with it alone. As she made the beds, shopped for groceries, matched slip-cover material, ate peanut butter sandwiches with her children, chauffeured Cub Scouts and Brownies, lay beside her husband at night- — she was afraid to ask even of herself the silent question — “Is this all?”. . .

He went on to talk about the abortion-rights movement (“Power wants to control women’s bodies… Power does not want to come to the table because it knows it will lose.”) And he characterized Roe v. Wade as “a moderate decision,” not radical at all.

He quoted Congresswoman Shirley Chisholm:

The law cannot do it for us. We must do it for ourselves. Women in this country must become revolutionaries. We must refuse to accept the old, the traditional roles and stereotypes. … We must replace the old, negative thoughts about our femininity with positive thoughts and positive action. . . .

And he cited Susan Brownmiller’s classic Against Our Will, which inspired women to fight back against rape culture.

Often what passes for “a good man,” Daisey observed wryly, is just someone who’s “way less rapey than the other ones.” Then he told about the time he was in a bar and saw a man “being rapey” toward a woman. He was not a silent bystander; he intervened, effectively. And his description of how scary and necessary that act was sent a message to the men in the room.

Underscoring the intersection of racism, classism, and sexism, Daisey quoted a woman named Johnnie Tillmon:

I’m a woman. I’m a black woman. I’m a poor woman. I’m a fat woman. I’m a middle-aged woman. And I’m on welfare. …

Welfare’s like a traffic accident. It can happen to anybody, but especially it happens to women….

And that is why welfare is a women’s issue. For a lot of middle-class women in this country, Women’s Liberation is a matter of concern. For women on welfare it’s a matter of survival.

The second revolution Daisey talked about was the movement that began with riots inside “the prison industry.” In Zinn’s words,

Literature about the black movement, books on the war, began to seep into the prisons. The example set in the streets by blacks, by antiwar demonstrators, was exhilarating — against a lawless system, defiance was the only answer….

Such injustice deserved only rebellion.

Among the political prisoners who resisted was George Jackson, whose book Soledad Brother, written inside San Quentin, radicalized many. After Jackson was “shot in the back by guards while he was allegedly trying to escape,” there was “a chain of

rebellions” in prisons around the country.

The third revolution Daisey touched on was that of the First Nations, who were rising up, reclaiming their tribal identities, refusing to be absorbed into the white man’s culture, and demanding, among other things, their rights under treaties that the U.S. had broken with abandon. That any First Peoples survived at all was not what the early American genociders intended.

A dramatic galvanizing event of their resistance happened when 78 Indians occupied Alcatraz Island in San Francisco Bay. The action, in Zinn’s words, “burst through the invisibility of previous local Indian protests and declared to the entire world that the Indians still lived and would fight for their rights.”

Like the recent #MeToo movement, these revolutions in the ’60s and ’70s “came from interconnected networks from the bottom up,” Daisey said. And his intersection of this chapter’s three revolutions conveyed a powerful coherence: Men’s subordination of women is connected to the the prison industry’s subordination of black men is connected to the government’s subordination of First Nations.

Chapter 12: The Black And Silent Wall, July 14 2pm

The chapter would be begin and end with a wall. The first wall was the Malecón in Havana, where Daisey visited some years ago. The final wall was the Vietnam Memorial on the Mall. In between was a narrative of U.S. military and diplomatic blunders, mass killing, and overweening imperialism interwoven with the moving story of how a war affected a father-son relationship.

Daisey chose to start with the Bay of Pigs as “a stand-in for all the shit America has fucked up.” America “sees itself as a democracy that never invades anyone” although it has “upended democracies around the world.” During the postwar cold war with Russia, America was driven by the domino theory, worrying that countries would catch communism “like measles.” It was a naked power grab by capitalism.

“The essential soul of America is neurotic and conflicted,” said Daisey, and “America is ashamed that it didn’t solve Cuba problem.” A hundred miles from Florida, a tiny country had “defied an imperial power.” So the CIA hatched a plan to settle the score, and JFK signed off on it. The idea was to launch a fake resistance—mercenaries and Cuban ex-pats equipped with U.S.-made munitions—that would sail into the Bay of Pigs and “make a show of fighting.” Then a flotilla of warships nearby would attack Castro’s Cuba as if in backup support. (In previous chapters, Daisey had described this basic game plan: America, which believes itself to be never the aggressor, always arranges pretexts for its military exploits, “to trick the world into letting the U.S. invade.”)

Daisey read a passage from Zinn that underscored the hypocrisy:

Four days before the invasion — because there had been press reports of secret bases and CIA training for invaders — President Kennedy told a press conference: “. . . there will not be, under any conditions, any intervention in Cuba by United States armed forces.”

“The CIA is drunk on white supremacy,” said Daisey. “The CIA is the way America fucks the world.” The Bay of Pigs was a debacle.

An even greater catastrophe was America’s role in the Vietnam war. An overview from Zinn:

From 1964 to 1972, the wealthiest and most powerful nation in the history of the world made a maximum military effort, with everything short of atomic bombs, to defeat a nationalist revolutionary movement in a tiny, peasant country — and failed. When the United States fought in Vietnam, it was organized modern technology versus organized human beings, and the human beings won.

Step by step, Daisey traced how America got into that mess in the first place—through successive periods of colonialism by the French and Japanese alongside decades of resistance by the Vietnamese. And the shocker, the big takeaway, was that as documented in the Pentagon Papers, “both countries [North and South Vietnam] and both sides of this war were invented by us.”

The Gulf of Tonkin attack under Johnson was another fake incident intended to justify military intervention. American officials blatantly lied to the American public, exactly as happened with the Bay of Pigs invasion. Daisey pointed to a recent instance of the tactic: the drone shot down by Iran that nearly triggered a war. Trump ordered the military on high alert, an attack was imminent, and then he asked, “Is anyone going to die from this?” When told the expected casualty count, he backed off.

“God bless his chicken-shit heart,” said Daisey.

The United States, which hundreds of years before “genocided a continent,” hammered Vietnam as though to “eradicate them.” It was “total war.” To put the devastation in context, Daisey quoted Zinn:

By the end of the Vietnam war, 7 million tons of bombs had been dropped on ‘Vietnam, more than twice the total bombs dropped on Europe and Asia in World War II — almost one 500-pound bomb for every human being in Vietnam.

The estimated death toll was 3.1 million, for which the only rationale can be racism, said Daisey: “They are less human than you.”

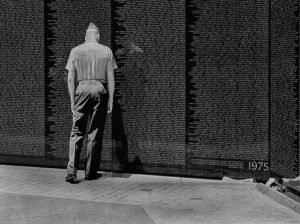

“I grew up with the fact of it, with what the war did to people,” Daisey said, because his father returned from Vietnam with PTSD. His father became a therapist who runs support groups for other service members with PTSD. Daisey has gone with his dad when they have taken groups to visit the “black glassy wall” of the Vietnam Memorial, which Daisey said is “a holy site for my father.” Daisey and his dad are very close. “But he left part of himself over there. He’s not entirely here.”

The toll of U.S. service members who died in Vietnam is 52,000. To add the 3.1 million Vietnamese who died “would need 70 memorials,” said Daisey. “It would fill the Mall with a river of black stone.”

Even now “we have concentration camps at the southern border,” Daisey reminded us. “We are the same nation, these are the same systems, this is our heritage, this is who we truly are.”

Chapter 11: The Revolutionary War, July 13 8pm

The chapter’s title refers to the Civil Rights Movement, and Daisey’s telling of it turned personal from the start. “I can’t see my own racism,” he acknowledged—by implication on behalf of his mostly white audience as well. He admitted being embarrassed about his racism and feeling awkward about not knowing the right thing to do or say—an experience the white audience could also likely relate to. And then he challenged them by telling about becoming mindful about who he spends time with, and affirmatively making sure his friendships include people of color. It was a provocative preface to his stories about the black revolt in the ’50s and ’60s under the weight of white supremacy.

He quoted a 1930s poem by Langston Hughes:

What happens to a dream deferred?

Does it dry up

like a raisin in the sun?

Or fester like a sore —

And then run?

…

Or does it explode?

The Civil War did not bring freedom; reconstruction failed. And “black people were

fed up about being held down for so long.”

America by this time was a superpower—”with the power to erase human civilization.” Its cold war rival was another superpower, the Commuinist Soviet Union, which mocked the way America posed as as beacon of democracy but derogated black people. “Russia convinced the world America is a shithole country,” said Daisey.

“Power never ‘gives’ rights,” Daisey reminded us. “If power does it’s because it is forced to.” So it was that in the case of “the race question”—a blatant contradiction of America’s ostensible ideals—America was having a global PR problem, which is why Truman had to do something. He appointed a committee, and Daisey quoted from its CYA report as reprinted in Zinn:

We cannot escape the fact that our civil rights record has been an issue in world politics. The world’s press and radio are full of it. . . . Those with competing philosophies . . . have tried to prove our democracy an empty fraud, and our nation a consistent oppressor of underprivileged people. . . . The United States is not so strong, the final triumph of the democratic ideal is not so inevitable that we can ignore what the world thinks of us or our record.

Afterward Truman took the laudable step of integrating the armed services, but that too was power responding to pressure; he was getting heat from a progressive candidate he was running against.

Daisey quoted Rosa Parks three months after her arrest for refusing to obey the segregation law on a Montgomery bus: “When and how would we ever determine our rights as human beings?” The ensuing boycott sparked nationwide attention and was joined and supported, Daisey pointed out, by trade unionists and socialists.

Daisey also shared Dr. Martin Luther King’s stirring oratory:

We have known humiliation, we have known abusive language, we have been plunged into the abyss of oppression. And we decided to raise up only with the weapon of protest. It is one of the greatest glories of America that we have the right of protest.

If we are arrested every day, if we are exploited every day, if we are trampled over every day, don’t ever let anyone pull you so low as to hate them. We must use the weapon of love. We must have compassion and understanding for those who hate us. We must realize so many people are taught to hate us that they are not totally responsible for their hate. But we stand in life at midnight, we are always on the threshold of a new dawn.

It was then Daisey talked personally again about “what it means to have black people in your life.” He told of his boyhood friendship with Doug, who is black. They were fellow geeks into comic books and Dungeons and Dragons, and as they grew older Doug was to school Mike about his racism. Mike got into college prep courses; Doug did not. It wasn’t because Mike was smarter—Doug had prodigious knowledge of the universe of Marvel comic books. It was because Mike was white.

“They don’t give you a model” for how to work on your racism, Daisey said. “You practice human kindness and openness and you check yourself.”

The heat and intensity of nonviolent resistance caused power to “blink,” said Daisey, “but power did not concede.” The 1968 Civil Rights Act contained a section that was used as a tool to suppress black violence and rage. The law made it a crime “to organize, promote, encourage, participate in, or carry on a riot” and it defined a riot as any action by three or more people involving threats of violence.

After the historic 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, Dr. King turned his attention to class inequality and set out to form an alliance between black and white workers and communicate the connection between racism, war, and poverty.

It was “no coincidence” Dr. King was assassinated, Daisey said. He had been taped and blackmailed by the FBI. “He refused to be controlled, then is killed.”

Chapter 10: The American Kryptonite, July 13 2pm

The chapter was going to be about “the one good war”—when “we get to punch Nazis.” In fact for a long time, going back to 1936, “we made a point of doing nothing…not stopping Hitler but helping by doing nothing.” Not until Pearl Harbor did America leave the sidelines and join the conflict..

The delay was uncharacteristic, because “America doesn’t like to intervene but does it all the time.” Citing instances prior to Pearl Harbor, Daisey illustrated “the way our military creates intervention,” which is to “create intensity” and “escalate tension” in order to “goad other people to hit us first.”

This is not how America likes to think of itself, of course, and so a “narrative about sneak attack” has been the official line on why the U.S. got into World War II. Not coincidentally this was the same cover story floated to explain how the Mexican-American war began.

In fact in the weeks before Pearl Harbor, America instigated several “provocative acts toward Japan,” including “cutting off supplies.” President FDR was “a schoolyard bully,” said Daisey. “He wanted a war, and he creates it.” So there was the routine goading into conflict. “Then they hit us harder than we expected.”

After the Pearl Harbor attack, the U.S. in effect approximated the fascism it had gone to war to fight. Daisey quoted Zinn:

Franklin D. Roosevelt … signed Executive Order 9066, in February 1942, giving the army the power, without warrants or indictments or hearings, to arrest every Japanese-American on the West Coast — 110,000 men, women, and children — to take them from their homes, transport them to camps far into the interior, and keep them there under prison conditions. … The Japanese remained in those camps for over three years.”

Daisey read from Zinn about a 1945 article in Harpers that called the internment camps “our worst wartime mistake”:

Was it a “mistake” — or was it an action to be expected from a nation with a long history of racism and which was fighting a war, not to end racism, but to retain the fundamental elements of the American system?

The war was not fought on American soil. “We are far away from it; all the deaths are on other lands.” Countries there are “scarred by death.” After the war the full extent of the Allies’ saturation bombing became known. Its targets were not military; its purpose was to undermine the morale of the German people, and it culminated in the firebombing of Dresden, which left 100,000 civilians dead. As a consequence of wartime horrors, European nations are “now actively less imperialist.” Meanwhile America’s imperialistic military exploits, as in the Middle East, have continued apace, often over oil. Daisey quoted Zinn:

In August 1945 a State Department officer said that “a review of the diplomatic history of the past 35 years will show that petroleum has historically played a larger part in the external relations of the United States than any other commodity.”

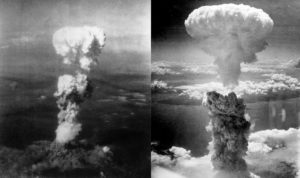

When in August 1945 America dropped two atomic bombs on Japan, there was a backstory rarely told, said Daisey: “Japan was trying to surrender,” meaning there “was no justification” for the destruction. “We used all the bombs we had.” If there were more, speculated Daisey, we’d probably have used them. “When we were out of bombs we accepted surrender.”

“That is the moment when America becomes a superpower,” said Daisey. “That is the moment that we have the power to destroy the world.”

Daisey returned to a theme running throughout A People’s History: “The essence of American exceptionalism is genocide and slavery. ” And he related it to the present chapter: “The Nazis are pussies compared to us.”

Another theme of the series been America’s “blind spot” about the facts of its past. And here Daisey called attention to how Americans “demonize the Nazis” and make Germany “the bogeyman”—”because we never talk about what we do to our own people. We can’t talk about the parts of ourselves that’s like them.”

And he reiterated how future generations will assess this time when “we fucked the planet. We sucked carbon out of the earth and sent it into the atmosphere.” The earth is burning from the heat. And, said Daisey, citing the IPPC report on global warming, “there is no good scenario.”

The cryptic title about kryptonite became clear when Daisey told of a visit he made to Los Almos to see the crater where America’s first atomic bomb was detonated. Despite cleanup efforts, the site is still radioactive. The heat of the explosion—for a hot second it surpassed the surface of the sun—melted the sand and turned it into a green glasslike substance now called trinitite, pieces of which can still be seen. Daisey dubbed it America’s kryptonite, “our birthright,” because it is both so beautiful and so lethal.

Chapter 9: The Hunger That Waits, July 12 8pm

Between 1798 and 1895, American armed forces made more than a hundred overseas forays and interventions in the affairs of other countries. We don’t get told this in the default American history. Then as now, the pretexts given for these military exploits were not the real reasons. In Howard Zinn’s words, these “foreign adventures” were meant to “deflect some of the rebellious energy that went into strikes and protest movements toward an external enemy” and “unite people with government, with the armed forces, instead of against them.”

But the main reason for these exploits, Daisey told us, was that America needed to prove how powerful it is, to show other nations that it’s a world power. And “people who have to prove how powerful they are have to keep doing that.”

This was not the first time Daisey had personified America in terms that mapped to how insecure men act. Or as Daisey specified, America was acting “like a pent-up schoolyard bully, like an incel.” And further, Daisey said, America was so expansionist because it “had a fucked-up childhood”—its origin in genocide and slavery.

“The hunger that informs overseas adventures is key to who we are,” said Daisey, and his apt gendered psychographic for America could be heard in an editorial he quoted from Washington Post on the eve of the Spanish- American war:

A new consciousness seems to have come upon us — the consciousness of strength — and with it a new appetite, the yearning to show our strength. . . .Ambition, interest, land hunger, pride, the mere joy of fighting, whatever it may be, we are animated by a new sensation. We are face to face with a strange destiny. The taste of Empire is in the mouth…

The “we” in that editorial of course meant entitled white men, who could relate to it as could no one else. And at points in the chapter Daisey drew out a subtextual connection between America’s imperialism and men’s sexism. As in the previous chapter, he brought up the Kavanaugh hearings as an illustration of a man filled with rage that he is being accused, a rage that said, “How dare you question me?”

Women know this about men, Daisey said. “Women assess how likely a man will perform that rage.”

And then Daisey segued to disclosures about himself that seemed at times almost too honest for public performance. He told of his sexism and how it impacted a relationship such that he had to confront it and work on it. He gave as an example needing to learn to clean his own mess and clutter because he realized his expectation that his girlfriend would do it was sexist.

“Gentlemen, I began to clean up my shit,” he said.

At which point the audience burst into applause, which seemed to throw him. “Don’t applaud me!” he said.

Other historical topics that came up included the intense racism of the period. He quoted Zinn: “In the years between 1889 and 1903, on the average, every week, two Negroes were lynched by mobs — hanged, burned, mutilated.”

Daisey also talked about the massive income inequality, which is “a hallmark of America” and is worse now than then. Also the financial crashes throughout the 19th century, when “capitalism folds in on itself.” Also the literal hunger and desperation of people during the Depression. Also the coming climate catastrophe, “the end of this world that we now live in,” which “a society already good at not looking at genocide and slavery” is now also ignoring.

He closed with a poem written in the mid-thirties by Langston Hughes called “Let America Be America Again.” It said, in part,

I am the poor white, fooled and pushed apart,

I am the Negro bearing slavery’s scars.

I am the red man driven from the land,

I am the immigrant clutching the hope I seek—

And finding only the same old stupid plan.

Of dog eat dog, of mighty crush the weak. . . .

O, let America be America again —

The land that never has been yet —

And yet must be — the land where every man is free….

Chapter 8: The City That Was Free, July 11 8pm

Daisey began the chapter with a question, “What does it mean to be free?” And (jumping ahead to the end) the titular “city that was free” turned out to be Seattle, where for five days in February 1919, a general strike by 100,000 workers brought the city to a standstill.

In between that opener and that closer was an engrossingly annotated overview of “20th-century wonders and horrors,” with a focus on the rise of the labor movement.

But first some preliminaries about Daisey’s own employment history. As a teen in northern rural Maine, he once had low-paying work behind the meat and deli counter of a convenience store. Hunters would bring in deer to a shack out back to be bled and gutted. Daisey’s job was to squeegee the floor and dispose of the viscera. Anyone who had been following A People’s History was likely not surprised when Daisey read in those entrails America’s history of genocide, racism, slavery, and sexism.

With ICE anti-immigrant raids promised on Sunday, it was a particularly disconcerting moment for Daisey to explicate how white supremacy infects us (meaning ourselves and our nation) and the way we develop a “defensive shell that inures us to the issues of the world…that makes you not feel things.”

Except, of course, entitled white men are entitled to feel a conspicuously privileged kind of outrage, a characteristic “I don’t deserve this” indignation. “I call that a Kavanaugh,” Daisey cracked.

Flashback to the bad old days when the workweek was 70 to 80 hours and child labor was the norm. In 1907, a poet reporting on New York City sweatshops wrote in Cosmopolitan magazine (not the Cosmo we know today):

In unaired rooms, mothers and fathers sew by day and by night. . . . And the children are called in from play to drive and drudge beside their elders. . . .Nearly any hour . . . you can see them — pallid boy or spindling girl — their faces dulled, their backs bent under a heavy load of garments piled on head and shoulders, the muscles of the whole frame in a long strain. . .

The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in 1911—when 146 workers were burned or crushed to death—gets a mention in U.S. history textbooks. But typically left out of the narrative, said Daisey, is the activism that began two years before when the workers got together and voted to strike. They did strike. And police paid by factory owners struck back.

Workers were organizing for their lives, and unionization was growing—but even in unions inequality was institutionalized. Daisey quoted Zinn:

Shortly after the turn of the century there were 2 million members of labor unions (one in fourteen workers), 80 percent of them in the American Federation of Labor. The AFL was an exclusive union — almost all male, almost all white, almost all skilled workers. Although the number of women workers kept growing — it doubled from 4 million in 1 890 to 8 million in 19 10, and women were one-fifth of the labor force — only one in a hundred belonged to a union.

Black workers in 1910 made one-third of the earnings of white workers [and were] excluded from most AFL unions.

A new direct-action mobilization nicknamed the “Wobblies” (the Industrial Workers of the World) aimed to create one big union “undivided by sex, race, or skills.” It started at a convention in Chicago in 1905 of two hundred socialists, anarchists, and radical trade unionists from all over the country. Daisey quoted from Zinn an address by a leader at that gathering:

Fellow workers. . . . This is the Continental Congress of the working-class. We are here to confederate the workers of this country into a working-class movement that shall have for its purpose the emancipation of the working-class from the slave bondage of capitalism. . . . The aims and objects of this organization shall be to put the working-class in possession of the economic power, the means of life, in control of the machinery of production and distribution, without regard to the capitalist masters.

Others who spoke included Eugene Debs, the leader of the Socialist party who was to run for president, and Mother Mary Jones, after whom the progressive magazine is named. The radical Wobblies’ constitution laid it on the line:

The working class and the employing class have nothing in common. There can be no peace so long as hunger and want are found among millions of working people and the few, who make up the employing class, have all the good things of life.

“I know you’re not radicals,” Daisey joshed. “I won’t condemn you for that, because you’d do that yourself.” But never one to avoid reminding his audience we are implicated by our privilege, Daisey did a riff on the 401(k) as an example of what makes one a member of “the investing class.”

“Power is clever,” said Daisey, but “agitation causes power to blink, negotiate.” For instance, he told of activist efforts that resulted in the FDA and FTC—”regulation to protect people that would not have shown up but for organized agitation”—because “if something becomes a wave and starts to grow, power freaks the fuck out.”

A tangent about “the rotten orange pumpkin in charge of the country” thrust the themes in this chapter into the present. “He goes to dictators and admires their power. He tells them he loves them because he does love them.” In his “venalness and stupidity,” he is the “least-deep person,” Daisey said; “he would be more dangerous if he weren’t as stupid.” But “someone smarter is coming,” Daisey warned, and if we think what Trump has unleashed will be over when he’s gone, we are “fools.”