I saw Jackie Sibblies Drury’s Fairview opening night at Woolly, and I cannot stop thinking about its originality—not only in form but in intent. I’m not writing about the production—my colleague Amy Kotkin did the DCMTA review—but if I were, there’s so much I wouldn’t want to give away that all I would say is: Just go see this play.

Woolly has done some brilliantly disruptive plays in the past. I’m thinking of Gloria and Kiss, which I loved, where midway through, the form of the play cracks open into a whole new theatrical dimension. Fairview goes even further. By my count it cracks open four times.

Fairview is explicitly about race, and as such it asks everyone who sees it to acknowledge their own. I’m descended from Norwegian and German immigrants, which in America translates to white. And I cannot recall anything in theater that so intensively makes a white audience member conscious of their whiteness as something that takes up space.

Fairview begins the first season programmed by Maria Manuela Goyanes, who has been on the job as Woolly’s artistic director for a year. In a warm phone call just after Fairview opened, I asked her how she was feeling. “Grateful and appreciative of the DC community,” she said. “Very embraced and excited to be here. Really appreciative of the staff.” And then we got down to an extraordinarily frank conversation about Fairview the play, race in DC, and what’s ahead at Woolly.

John: When you programmed Fairview, what were you thinking?

Maria: I saw the play in New York on the fourth preview, and I was blown away by it. This was before it won the Pulitzer, before people were talking about it. And I found myself having a transformative experience. I identify as Latina, but I’m very white-presenting. So I found the play to be thrilling and difficult and challenging. And I remember going up to Jackie [Sibblies Drury] afterward. I knew she was a Woolly playwright because we had done her We Are Proud to Present, her breakout play, not too long ago. I had just gotten the job at Woolly. And I said: Please let me do this in my inaugural season at Woolly. My instinct and intuition was: This is the conversation I need to be having.

I hadn’t even moved to DC yet. So when I did finally move to DC and talked to folks about the play and had my senior staff read it and started to get to know the city, I realized: DC was a majority-black city until recently. It’s still majority people of color. And I thought to myself, in terms of a season opener, it was important that people knew that Woolly was going to do thought-provoking work and challenging content—that finding me and having me take over for Howard [Shalwitz] didn’t mean we were going to be any less risky in the work we were doing.

But then I also thought to myself: What is the most urgent conversation I want to be having with my company of artists as well as with the audiences? And it felt like Fairview checked all those boxes in the most exciting way—and in a scary way. It’s a very bold move for the first show. And I think that says I’m doing something right when it comes to Woolly Mammoth.

When you programmed Fairview, in what sense did you see it as a play for white people and in what sense is it a play for people of color?

Well, here’s the thing I want to tell you: I don’t want to prescribe an audience’s reaction to the show because I think that can be harmful. And what do I know ultimately in terms of that? However, we are doing a community conversation after every performance for folks who want to process it, and in the community conversation we are breaking folks by racial affinity.

I intentionally programmed Fairview next to What to Send Up When It Goes Down, which I cannot wait for you to see, John. Remember in the monologue that Keisha the daughter has at the end of Fairview where she says:

Keisha: If I could tell the story I want to tell us,

my people,

my colorful people,

you would hear it

if I could tell it,

and it would be something like

a story about us, by us, for us, only us.

For Woolly Mammoth it felt like: Well, then, that’s what we need to do. If we were going to take the challenge of Fairview, then we need to program after Fairview a show that is specifically about and for and by black folks.

What to Send Up When It Goes Down is about healing from racialized violence. It’s by the Movement Theatre Company, which is run by all people of color. Great, amazing young producers. And it is a play that is speaking to one of the most urgent issues that is happening to black folks in this country, which is anti-blackness, which has been the case for now centuries. For me Fairview and What to Send Up When It Goes Down are really of a piece. Even though Aleshea [Harris] and Jackie weren’t writing these shows to be seen together like this, they are both speaking to something that I’m incredibly passionate about—and it felt like Woolly Mammoth needed to answer the challenge that Keisha gives us at the end of Fairview.

Keisha also challenges the white people in the audience to think about “what you can you do to make space for someone else.”

Yeah.

That line just went boom for me.

That was exactly the thinking. If Fairview is about folks learning how to make space, then how does Woolly Mammoth make space? And that’s something to do with the new lobby, with What to Send Up When It Goes Down, with the intentionality of our work with connectivity.

Fairview holds up to critical view how white people view representations of black people in a particular comic sitcom. It now strikes me that the same dynamic—spectatorship through an unself-consciously white lens—is what’s almost always going on whenever white people watch plays about characters of color, even in stories told by playwrights of color.

For instance, when Woolly did BLKS, which I loved, that was a play the black playwright [Aziza Barnes] deliberately intended to be by and for black people, yet it was being hugely enjoyed at Woolly by audiences that were majority white. After seeing Fairview, I’m now wondering whether white audiences were even seeing the play the playwright wrote.

I don’t identify as white, right? Even though I’m white-presenting. To me the challenge I think—for you, John, or any white-identified person—is how to actually start to be able to lift and name and acknowledge what slavery did in this country. I mean, you see what’s happening, right? You see we can’t pretend that racism only exists if you wear a hood. It’s something that is operating all the time, and it’s a system that we all live in. So to me part of that conversation is how do we make space for other stories. And the act of witnessing is a different act than the act of identifying with, you know what I mean?

Wow.

To be able to see people with the fullness of their humanity, hopefully working toward creating greater empathy and understanding and more engaged citizenry in this country. That’s really what I think Aziza is doing for young twenty-something, queer, fem black women, you know, black folks. And BLKS is just like a day in the life: Look at what we have to deal with, think about, and be in conversation with. Acknowledgement of it is the first thing.

I’m mixed. My father is from Spain, from Hispanic culture and European culture, and my mother is Dominican. So I have to square my values and my intentionality having a deep understanding and analysis of what that means for me to move through the world. Certainly, my experience is different from black and brown folks, even in positions of power. I get to do things and be things because people don’t know where I come from. They don’t ask. They don’t assume those prejudices and biases come from the racist structures and systems that we live in. I have a lot of privilege in that way. So how do I move responsibly and intentionally? There’s just a lot of conversation to be had about it, no question.

Donna Walker-Kuhne wrote a really profound and practical book about multicultural audience development—

Are you talking about Invitation to the Party?

Yes. And it was based on her experience at The Public Theater in New York. So I wanted to ask you, since you have had experience working at The Public, what insights or lessons learned there do you think could be applied at Woolly in particular and in DC more generally?

Well first of all, let’s plug that book so that everybody reads it because Donna Walker-Kuhne is brilliant. A lot of the things she speaks about are foundational. The culture is shifting at great speed, and there’s great writing that is even more contemporary. The book by adrienne maree brown Emergent Strategy comes to mind. It’s a really amazing strategy book to help us do this kind of work. It’s like a little bit of a Bible for me. So I would also love to shout out that book.

The Public is such a larger scale than Woolly, and so for me what I want to lift here is that I feel really excited to have a local community that is as dynamic and rich and robust as Washington, DC, the DMV area. Woolly is a 265-seat house. I could actually know everybody in the audience on a particular night, which is a beautiful thing. And so I’m excited about those strategies that Donna talks about and that adrienne maree brown talks about and thinking about it at a hyperlocal level.

I know you asked me a question about The Public, but I want to bring it to Washington, DC, and the glory of being in a place where people are incredibly proud of being from this area. I’m getting to meet those folks and put some of these things into practice with this community and that’s tremendously exciting.

The aspiration that’s evident in the programming of Fairview makes me so excited about what you’re going to do next. I mean, it’s just a knockout season opener. It’s one of those plays that will alter people’s brain mapping.

Oh gosh I hope so, I love that.

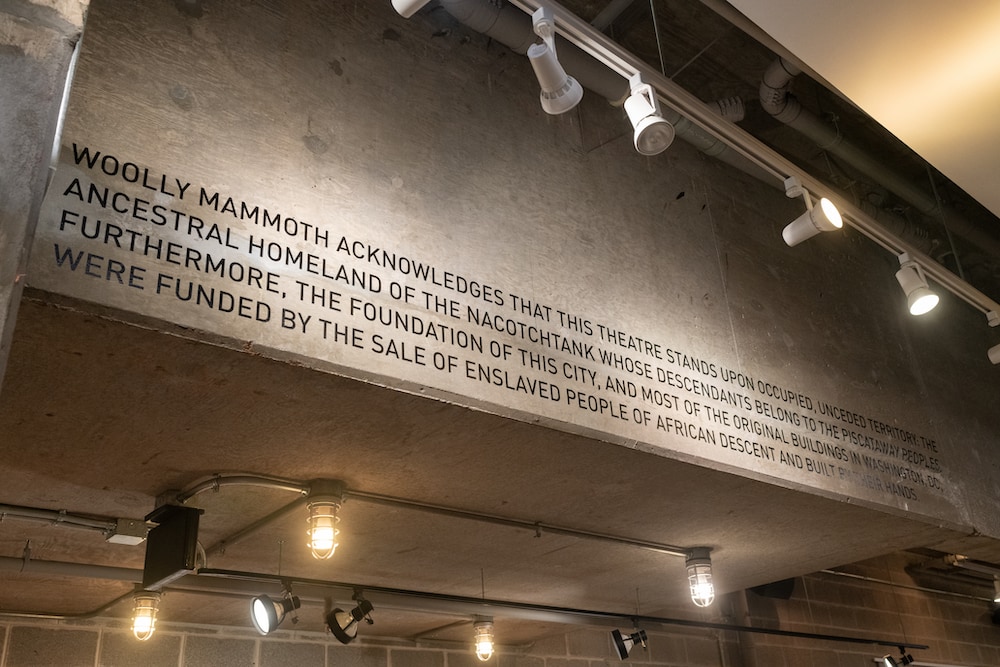

I attended the Woolly open house for its new lobby, which was the day after Fairview opened, and I was so moved by the new inscription on the wall. I just choked up looking at it as you read it aloud:

Woolly Mammoth acknowledges that this theatre stands upon occupied, unceded territory: the ancestral homeland of the Nacotchtank whose descendants belong to the Piscataway peoples. Furthermore, the foundation of this city, and most of the original buildings in Washington, DC, were funded by the sale of enslaved people of African descent and built by their hands.

It’s so consonant with everything you’re doing.

Thank you so much. It means a lot to me. And here’s the thing about all of the words up there on the entry wall, the land acknowledgement and the acknowledgement of the history of slavery: I hope it is not just going to be inspiring for folks who walk in, but also help us be accountable to those words. I hope that you as part of this DC artistic community will also help Woolly be accountable. It shouldn’t just be words.

Fairview plays through October 6, 2019, at Woolly Mammoth Theater Company, 641 D Street NW, Washington, DC. Purchase tickets at the box office or go online.

Running Time: One hour and 40 minutes, with no intermission.