To realize how much white America loved minstrelsy is a reckoning painful or shameful, depending on one’s ancestry. Minstrel shows were never meant for people of African descent to see; they were intended for white eyes only, and white people flocked to them.

In the guise of popular entertainment, minstrel shows functioned as anti-Black propaganda plain and simple. They spread degrading stereotypes of Black people to parts of America even before Black people got there. To find a modern-day equivalent one would have to join in the jingoistic jeering at a stadium Trump rally. “At one point,” says an actor in Theater Alliance’s theatrical clapback, “minstrel shows were bigger than baseball.”

Douglas Turner Ward’s 1965 Day of Absence: A Satirical Fantasy “was conceived for performance by a Negro cast, a reverse minstrel show done in white-face,” he wrote. Theater Alliance has expanded on the concept and staged the classic one-act preceded by cast-written sketch comedy—satires that roast and refute the prejudice to which minstrel shows pandered. And the subversive dramatic action begins the instant one steps inside the theater.

[READ Andrew Walker White’s rave review of Day of Absence.]

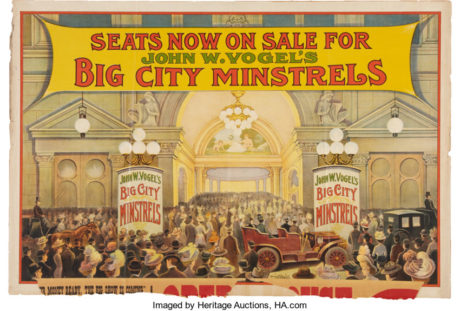

Standing eight feet high are massive historical posters for minstrel shows. They are disturbing to look at; one wants to hurry past them. Yet there is something strangely compelling about them, for they have been colorized with a painterly patina that attracts the eye even as the underlying imagery repels. Stepping further into the theater one sees a proscenium’s worth of such posters, suspended around the stage like a sideshow of grotesques rendered picturesque.

I do not recall a set design that so emphatically frames the esthetic and politics of the performance to follow. Here everything about minstrelsy is turned on its head. Here on in-your-face display is the iconography of white people’s historical derogation of Black people. And here simultaneously is its subversive reversal, a cooptation for opposite purpose, the conversion of artifacts of hate into objects of political art—and ultimately an insistence that the white gaze perceive itself.

The signs called for in Ward’s script were the “jumping off point,” Scenic Designer Jonathan Dahm Robertson told me. And “to stay true to the minstrel performance,” that idea evolved into posters from the period. “They were all incredibly easy to find,” Robertson said. “There’s a ton of them out there. We focused on ones with white people in blackface. Then we found a few just absolutely grotesque caricatures of Black individuals and Black performers. And we picked a balance.”

To control the color of each poster, Robertson prepared renderings showing how they should look when finished. Once printed out in black and white on a large format printer, the posters were mounted onto wood and became vast canvases for Scenic Artist Bridget Willingham to paint on.

“I had some freedom, like the texture,” Willingham told me. “The posters are very grungy. I was playing around with the paint and I would show it to Johnny and I was like, Is this too dirty? And he was like, No that looks perfect.”

Willingham shared with me her personal touch in the posters’ aged and weathered look. “For me when I was painting them I was heavily uncomfortable,” she said. “I didn’t know the show, and I was painting this very racist imagery. And the reason it was uncomfortable for me is because I don’t believe in these things. And I think I overloaded on the dirt—a lot of brown scumble everywhere—because I was trying to cover it up.

“When I learned what the show was about and the message they were trying to give to the world,” Willingham continued, “I felt better and more comfortable with painting them.”

Similarly Robertson shared that “when the cast first saw the posters, they were taken aback by them. But then they were impressed at the intention.”

That double-take reaction to the posters—which audiences can readily relate to—is a measure of the power of the design now on exhibit in Theater Alliance’s production of Day of Absence. One must look twice. Once to see in this imagery the hateful roots of American racism. And once again to see the artful way these reclaimed, rerendered posters frame an extraordinary evening of Black-centric subversion that should not be missed.

Running Time: One hour 40 minutes, with no intermission.

Day of Absence plays through November 3, 2019, at Theater Alliance performing at Anacostia Playhouse – 2020 Shannon Place SE, in Washington, DC. Purchase tickets at the box office, or go online.