Right to Be Forgotten is a play written from the outside in. By that I mean, its intention is to illustrate a legal issue: the tension in U.S. law between privacy and freedom of speech, a tension exacerbated by the internet. To lend that abstract conflict accessible emotional resonance, Playwright Sharyn Rothstein has crafted a human interest storyline about a young man named Derril.

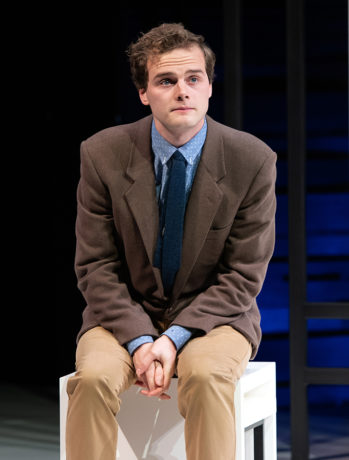

Derril (played arrestingly by John Austin) is haunted by online trash talk about a mistake he made ten years ago when he was a socially awkward 17-year-old. Derril is now a socially awkward grad student in literature who wants one day to teach. He knows his searchable past could derail his career. The plot turns on his efforts to get that youthful indiscretion expunged, or de-indexed, so that it no longer shows up when his name is Googled. He does not deny the mistake, which involved a female classmate. He just wants it digitally forgotten so he can move on.

[READ Bob Ashby’s review of Right to Be Forgotten.]

Rothstein’s script is razor smart. There are acerbic laugh lines aplenty and the story and stakes are clear as day. The production directed by Seema Sueko zips by like a high-tech legal procedural. Shawn Duan’s projections turn Paige Hathaway’s set into a manic smartphone screen; dazzling computer code floods the stage. The characters are precisely drawn and incisively performed. And I wanted very much to follow along with the play’s outward argumentation about how big tech companies cloak themselves in the first amendment to maximize profits from wholesale violation of people’s privacy.

But instead, I found myself watching Right to Be Forgotten from the inside out. By that I mean, my attention was commanded by Rothstein’s invented story centered on Derril, not the argumentation it was intended to illustrate. I wanted to know: What exactly did Derril do, and at what cost to the classmate to whom he did it?

In the first scene, Derril tells a young woman, Sarita (appealingly played by Shubhangi Kuchibholtla): “The me you meet online is going to terrify you.” They are on a sort-of first date; there is a sort-of attraction between them. Suddenly Derril blurts out a confession that his name is not what he told her it was; he has been using a pseudonym so his past shame won’t show up in search. And Sarita is promptly put off.

So not only could Derril’s online disgrace kibosh his career; it’s going to quash his love life. Thus motivated, Derril seeks out Marta (a delightful Melody Butiu), a shrewd privacy-rights lawyer, in hopes of getting that past erased. Marta proceeds to draw out of him the “he said” of what he did. And the script proceeds to position Derril as its hero, the aggrieved party.

Ten years ago Derril became besotted with a young woman classmate named Eve who had stood up for him when he was bullied and taunted for being gay. (He’s not.) He fast got a crush on her and kept following her and showing up at her house. He was not stalking her, he says, and he is not a criminal, he says; he just wanted to be near her—over and over for months. Marta is promptly suspicious of his hair-splitting.

Derril’s dilemma is that soon after his not-stalking-not-crime-committing, someone posted online a damning blog detailing his persistent unwelcome behavior. The blog went viral, and women added comments about men who had done unwanted things to them as well. So Derril’s name online is mud.

Marta, a sympathetic civil-rights activist at heart, takes Derril’s case. For the moment Derril’s conception of his dilemma is not the fact of what he did; it’s that it got exposed and damaged his reputation. In a move to repair it—and in one of the play’s many sharp twists—Marta concocts a PR scenario whereby Eve would go public forgiving Derril. Thus there comes a scene between Derril and Eve (an amazingly moving Guadalupe Campos), in which Derril is tasked with asking Eve for forgiveness. But the scene turns wrenching as we learn along with Derril that what he thinks he did does not approximate how Eve, to whom he did it, experienced it.

Promotion for Right to Be Forgotten has been at pains to frame what Derril did as a “mistake” and an “indiscretion,” and Rothstein’s script itself couches his misdeed as an enamored youth’s excess of infatuation with no malicious intent, not a smidgen of sexual predation. Then in that pivotal scene between Derril and Eve, this inside story’s stakes and Derril’s character arc take an abrupt turn.

Not to give too much away, but for the first time in the play we see Derril have to reckon with what his behavior did to Eve. He has to get out of his own head and hear out her heart. And he listens. And it changes him.

We don’t see the change in Derril right away. But there comes a scene a little later when he makes a decision motivated by that empathic learning that is expressly in Eve’s interest, not his own. Derril’s choice comes as a surprise, we don’t see it coming, but it is immediately credible and it lifts the stature of his character before our eyes. I so admire that moment and how Rothstein has prepared for it. It is the moral apogee of the play and for me the main reason Right to Be Forgotten needs to be seen. That moment needs to happen more in life.

That said, if I step back and look at Right to Be Forgotten from the outside in, to see how the Derril/Eve narrative is functioning to dramatize a contest between free-market capitalism and human-rights-based regulation, I get a little…annoyed. And the reason is that in the #MeToo era, it has become very problematic to treat sexual politics as a parable about something else—for instance to tell a story about unwelcome behavior by a man toward a woman and make it about his reputation online not her injury in life. In the real world (remember the Kavanaugh hearings?), exactly such gaslighting has been employed to protect perpetrators and impugn victims. Conflating the right to be forgotten online with a right to be forgiven is nonsense. I know of no moral universe in which forgiveness is an entitlement.

Rothstein gets this, I believe. If she didn’t, she would not have scripted that powerful moment when Derril gets what he did to Eve. Ironically, though, that inside moment exposes what’s muddled in the play’s outside argument: It deals only with harm to reputation. And that’s a very myopic and privileged notion of the real-world harms being done to people online. Or for that matter in life.

Running Time: 85 minutes with no intermission.

Right to Be Forgotten plays through November 10, 2019, in the Kogod Cradle at Arena Stage, 1101 Sixth Street SW, Washington, DC. For tickets, call 202-488-3300 or go online.