Now into his second year leading IN Series, the itinerant company based at the Source Theater, artistic director Timothy Nelson has not been shy about challenging opera’s status quo.

“I believe that changing perceptions about the who, what, why, and how of opera is the only way that opera has a future, so what I am really saying is that I want this company to be at the forefront of helping opera survive,” he said during a media briefing earlier this year.

To mostly critical acclaim, so far this season Nelson has presented a deconstructed version of Puccini’s Madama Butterfly that addressed racism, and a commissioned work combining the Blues with Shakespeare’s The Tempest that focused on what it means to be enslaved.

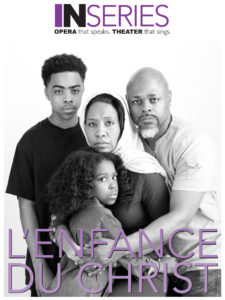

Next up is a look at what it’s like to offer what he calls, “radical and abundant hospitality” to refugees through the use of Berlioz’s L’enfance du Christ (The Childhood of Christ), co-directed by Nelson and Steven Scott Mazzola. Infrequently heard, the work is about the Holy Family’s flight into Egypt after Herod has declared all infant boys to be killed. In a Nelsonian twist, the oratorio will be staged in the Foundry United Methodist Church sanctuary with a professional and community choir directed by Stanley Thurston, as well as soloists, instrumentalists, and the church’s famed and recently refurbished organ.

Each performance includes guides who will lead interested audience members through nonspeaking roles as prophets, immigration agents, migrant workers and their families, angels, and hosts who welcome refugees. Following each performance, there will be an “action fair” offering social justice resources.

Leading up to the December shows, IN Series is holding Sunday gatherings to discuss social justice, art as spiritual practice, and how the act of making art can heal communities.

Recently, I sat down with Nelson, a protégée of the iconoclastic American director Peter Sellars, to learn more about the show and his vision for the future of opera.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Whitney M. Fishburn: There is a lot going on in the way you’ve envisioned L’enfance du Christ. I am not sure I have my arms around it. Can you explain the logic of it?

Timothy Nelson: Tell me about it! [laughs]. There is a lot going on. Berlioz conceived of the work as a triptych. If you look at it linearly, it’s in three parts. The first part is Herod’s dream and the massacre of the innocents, the center section is the flight into Egypt and resting on the way, and the final part is the family being welcomed into Saïs, which is the end.

Then it has an epilogue, which is told by a narrator who opens the piece by saying I will now tell you a story of the faith, and how when it’s all darkness, love blossomed for your fellow man. At the end of it, he says now let’s look forward to what’s going to happen, which is the resurrection and the forgiveness of mankind, but he opens it by saying, ‘Thus by the hands of an infidel was the Son of God saved.’

We never know the good we are doing, and who we might be saving.

But what about the logic of all the moving parts?

If you think of it as the triptych, then you’re focused on the center, which is the journey.

And we all get to take that journey if we’re part of the process. It’s that collective healing through art experience you talk about.

Yes. I want audiences in DC to be a part of the process of making opera, and in that way, demystify it and make it a spiritual experience. L’Enfance du Christ sits at the nexus of justice, art, and spirituality. I believe making art is a spiritual practice. As artists, we hope what we do changes the audience, but we know it changes us.

How do you define spirituality?

Good question. For me, it’s an experience that awakens, without needing an acknowledgment or understanding of what one is awakened to, but you know that feeling when something comes alive in you and for me, that is spiritual. That could be laughing with friends, great food, or being alone in the mountains, but it is that ineffable feeling.

In all my reviews lately, I try to address the deeper question I think everyone who loves opera should be asking: What is the point of it? Is it entertainment first, cultural second, the other way around, or something in between. What are your thoughts?

I loathe the idea of opera as entertainment. I don’t think being an audience member should be easy. You should be working as hard as the people on the stage, and then we meet somewhere in the middle. It’s like what the Greeks intended live theater to be: a place where the upper and lower echelons of society would come together to find solutions for problems.

Worship that is unconcerned with justice is vulgar, my pastor has said. For me, the same is true for art that isn’t concerned with justice. Opera has the potential to be the most powerful art because it combines everything. Music speaks to places words can never go. People can ultimately be moved by opera in ways they can’t with just theater, even Shakespeare, but we do that so rarely with opera.

How do you respond to critics of your innovations?

The comment that upsets me the most, although it’s so ridiculous it doesn’t really upset me, is that I don’t respect the composer. I always start with listening to the composer. I start with listening to the music for some truth that is beyond the text, beyond stage direction, beyond the setting, beyond everything.

Sounds like jazz.

Yes, I treat opera that way. In opera, we always assume that the text is telling the truth. For example, in Don Giovanni, he is seducing the women, so he must not be feeling anything for them, that it’s all just about sex. That is clearly not what Mozart’s saying with the music. When directors stage that scene, they stage the text instead of listening to the music and hearing the love and pain in Giovanni. He is not a monster. He is hurting. So, when I do it, I start with the wound. All the pain Giovanni causes is because he knows he is dying and he is acting out of this incredible anger of the unfairness of it.

You left an acclaimed career directing opera in Europe. What brought you to Washington?

The day I decided to move back was the day Trump was elected. I couldn’t live with myself watching from the cheap seats over in Europe where making art is easy, where there is a lot of money for it, and where there is a high standard of living. I wanted to come back and feel like I was making a difference.

Do you think Washington audiences want to be challenged the way you intend to challenge them?

I think we all want to be challenged, we just don’t know it. It is possible to offer challenging works that also make people feel so edified, they don’t care [that it was hard work]. It’s hard to sell new interpretations in this city because there is so much theater, and it’s the theater audience that I want. People need to be convinced that theater that makes them work harder is actually more worth it to them. And it will take years to convince them of that. That’s okay.

Running time: Approximately 90 minutes with no intermission.

L’enfance du Christ by Hector Berlioz also will feature Kerry Wilkerson as Herod and the Father; Elizabeth Mondragon as Mary; Jarrod Lee as Joseph; set design and art installation by Jeff Rivers and Yacine Fall.

Pre-show discussions:

November 10, 2019: Faith and Justice with Rev. Mark Schaefer

November 17, 2019: Faith and Art with Kevin Newell

November 24, 2019: Turning, Turning, with Sufi Whirling instructor Bedi’a and Beatbox artist Shodekeh

L’enfance du Christ will run December 7th, 2019 – December 14th, 2019, presented by IN Series and Foundry United Methodist Church, 1500 16th Street NW, Washington, DC. To purchase tickets, go online.