The pipeline in the title of Dominique Morisseau’s play is the “school-to-prison pipeline” affecting young African-American men. Fueled, as Studio Theatre’s dramaturgical notes explain, by a combination of in-school police officers, harsh zero-tolerance policies, and funding shortfalls, the pipeline progresses from the classroom to suspension or expulsion to juvenile court to adult prison, feeding the mass incarceration well documented by Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow.

But what does it feel like to be caught up in the entryway to the pipeline, the schools? That is the territory that Morisseau’s lyrical, eloquently expressive script explores.

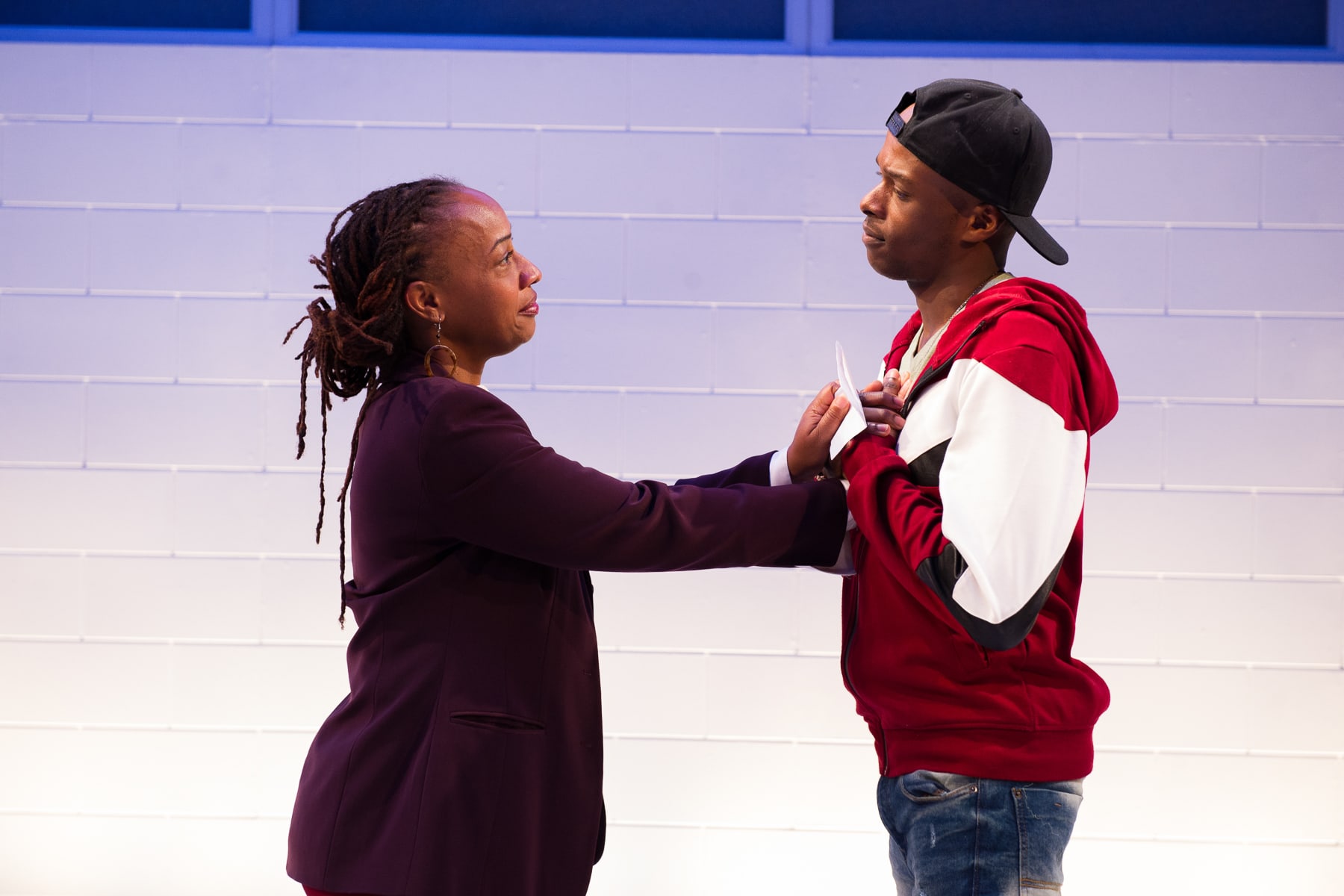

Nya (Andrea Harris Smith) stands at the intersection of two parts of this entryway. She is a teacher in an inner-city high school where resources are scarce, fights among students are common, and teachers are bone-weary. And she is the mother of a bright, angry, vulnerable teenage son, Omari (Justin Weaks). Nya and her ex-husband Xavier (Bjorn DuPaty) have placed him in an expensive, mostly white, boarding school upstate, hoping to insulate him from the perils of the city. Omari is in crisis: having shoved a teacher, his third disciplinary offense, he is in danger of expulsion or even criminal charges.

Nya fiercely seeks to protect her son. She interrogates him, his girlfriend Jasmine (Monica Rae Summers Gonzalez), Xavier, herself – what has happened, and why? How to prevent Omari from being sucked into the pipeline? To which director Awoye Timpo adds “Who are we? Who do we want to be? And how on God’s green earth are we going to get there?” Asking hard questions that lack definitive answers is central to the play.

The educational system itself comes in for hard scrutiny. Represented by Nya’s colleague Laurie (Pilar Witherspoon), profane and brimming with frustration, and Dun (Ro Boddie), a school security officer trying against heavy odds to keep up with his job’s demands, the play portrays a system struggling to keep its head, and those of its mostly minority students, above water. Meanwhile, the implicit biases of Omari’s private school disserve students of color.

Morriseau explicitly relies on the tradition of African-American literature to make her points, repeatedly referencing a brief Gwendolyn Brooks poem, “We Real Cool,” about young black men: “We Real Cool. We/Left school. We/Lurk late. We/Strike straight. We/Sing sin. We/Thin gin. We/Jazz June. We/Die soon.” Later in the play, as Omari tries to explain to his father the incident in which he pushed his teacher, Omari refers to Bigger Thomas, the protagonist in Richard Wright’s Native Son. Why did the white teacher single him out to explain the character’s motivation? At the same time, Omari seems in part to embody a comment by James Baldwin that “No American Negro exists who does not have his private Bigger Thomas living in his skull.”

There’s a much older literary tradition that underlies the structure of Pipeline, that of classical Greek tragedy. As in, for example, Medea, key events happen offstage. The audience does not see Omari’s confrontation with the teacher, Laurie’s breaking up a fight, or the strains that led to Nya’s divorce. What creates the play’s dramatic tension is less the events themselves than the characters’ reactions to them and each other.

In conveying that tension, the play creates a consistently high level of emotional intensity. Timpo and the cast maintain that intensity in a way that never descends into scenery-chewing. When there is a quiet moment, it has all the more impact, as when Omari tenderly takes a cigarette from his mother and snuffs it out.

When the intensity and pressure focused on a character become too great, something breaks: Omari pushes his teacher, Laurie whacks a fighting student with a broom, Nya suffers a panic attack, and Xavier almost wordlessly retreats from his son’s indictment. The characters are under unremitting stress from their environment, including its built-in racism, and such a break can happen almost anytime, without warning.

The mother-son relationship is at the center of Pipeline, and Smith and Weaks portray it in all its complexity. The supporting characters get their moments to shine as well. DuPaty conveys Xavier’s corrosive distance from his son, Laurie’s burnout is palpable in Witherspoon’s performance, and Gonzalez’s final monologue, mourning the loss of a first love while maintaining her hope for the future, is a gem.

Arnulfo Maldonado’s set, with its shiny white floor, spare institutional back wall, and few furniture pieces, establishes the barren tone of the institution in which Nya works, as do the generally white tones in Jesse Belsky’s lighting design. Sarita Fellows’ costumes – Xavier’s electric blue suit, the informal work attire of Nya and Laurie, the transition of Omari’s dress from prep school uniform to streetwear – underline the actors’ characterizations. A highlight of Fan Zhang’s sound design is the whispered underscoring of lines from Brooks’ poem, in one case doubled by Alexandra Kelly Colburn’s projection of the close-up of a mouth uttering the words.

Both Ben Brantley’s review of the original New York production and Studio artistic director David Muse’s program note use the word “fatalism” to describe the attitude of Pipeline’s characters. I respectfully disagree. They do not exhibit the hopelessness, indifference, resignation, or yielding to inevitable, pre-ordained fate properly associated with that term. As presented in this production, they are unillusioned about the power of the obstacles they face, but they stay in the fight and never stop trying to understand.

They get no final answers. Nor does Morisseau provide any for the audience. When, at play’s end, Omari presents Nya with a list of instructions, focusing on providing enough space for him, and implicitly all his peers, to develop in their own way, the last item on his list is left blank, for the audience to fill in. The lights come up full and bright across the stage for the first time, the lighting cue saying as much as the words about the show’s ultimate direction.

Running Time: One hour and 35 minutes, with no intermission.

Pipeline plays through February 23, 2020, at Studio Theatre, 1501 14th Street NW, Washington DC. For tickets, call the box office at 202-332-3300 or go online.