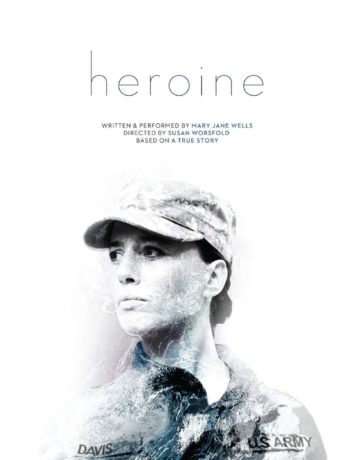

Post-Play Palaver is an occasional series of conversations between DC Theater Arts writers who saw the same performance, got really into talking about it, and decided to continue their exchange in writing. That’s what happened when Senior Writers and Columnists David Siegel (In the Moment) and John Stoltenberg (Magic Time!) saw the U.S. premiere of Heroine at The Kennedy Center.

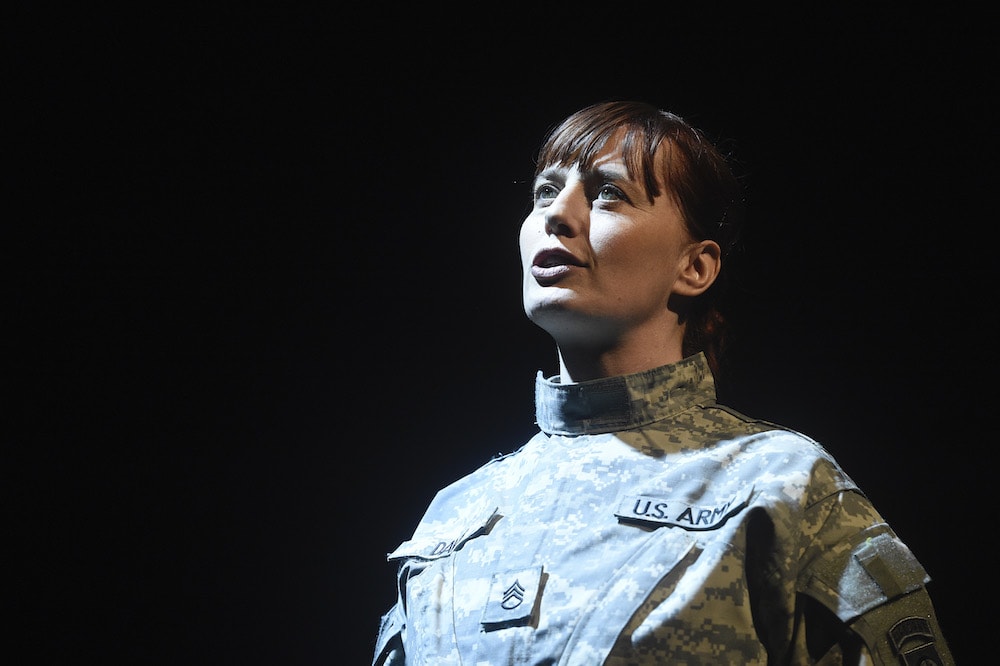

A hit at Scotland’s Edinburgh Festival Theatre, Heroine was written and performed by British actor, writer, and voiceover artist Mary Jane Wells. She performs alone on stage wearing a U.S. Army camouflage uniform. In a 2017 interview, Wells described her show in these blunt and personal terms:

Heroine is a one-woman show based on the true story of Danna Davis, who is a personal friend. She served as a lesbian soldier in the U.S. Army for ten years during “Don’t Ask Don’t Tell.” The only woman in her entire company, she is also a survivor of MST [military sexual trauma]. She worked her way up to be a squad leader and one of her assailants was placed in her squad.

When she led a dangerous mission into a combat zone in the Middle East, both he and Danna were practically the only ones to survive it, because she carried him home on her back.

It is an incredible true story that explores who you have to become to heal and move on with your life, and what you have to give up to forgive.

David: Leaving the performance of Heroine at The Kennedy Center, I was in silence. I had just witnessed and taken into my very core a harrowing production about the horror of sexual violence and the absolute terror of being in wartime military service. I needed time to process all that I had witnessed. There are so many layers to unpack for what is not a relaxed performance for anyone with a beating heart.

John: The scene where Wells enacts Danna Davis’s gang rape by fellow soldiers was searing, almost too hard to take in. “We’re gonna make a real woman of you,” she quotes an assailant saying to her. I cannot imagine how that scene landed for rape survivors in the audience. (Davis prefers to say of herself not that she is a survivor but that “I am a rape exister.”) The trigger warnings that precede the show are there for good reason.

Besides Wells’s excruciating depiction of sexual assault in the military, another thing really struck me: The fact that Davis’s rape happened during Don’t Ask Don’t Tell (DADT) meant that if she ever reported it, she could be outed as a lesbian and dishonorably discharged from the military service she felt so committed to—meaning her assailants knew they could get away with it.

“I wanted to rape them back,” she says.

A post-show panel of experts made clear that even as rates of reporting have risen, incidents of sexual assault in the U.S. military have been steadily increasing. Also, despite the end of DADT, there still is a stigma on being LGBT that inhibits reporting. So Heroine is in no way dated; it is right now. And the national silence about military sexual trauma—when all the talk is of increased defense spending—is a national disgrace. I salute Mary Jane Wells not only for her extraordinary performance but also for her bravery in exposing this Achilles’ heel of our American military.

David: Yes, you are right. What also struck me deeply, as one who served in the military, was the depiction of a firefight—in this case in an alley somewhere in Iraq. Over the past years I have been asked to review a number of theatrical productions about war. Each shakes me, as did Heroine.

In Heroine the firefight began with Mary Jane Wells depicting Davis’s role as a squad leader in charge of a vehicle driving along being hypervigilant and then…to be attacked. It was a production scene full of noise and lighting and the intense inner monologue of Mary Jane Wells as the squad leader. As squad leader, she was responsible for those with her. She had to make command decisions affecting the lives of those with her, including the life of the soldier who raped her. Her inner turmoil was clear. I can’t explain military service, other than how we were trained to take care of one another during such situations. (Though the final scene in Platoon was likely all-too-real, and certainly as a one-time military officer, the word fragging has meaning to me ).

I also could understand why squad leader Wells (portraying Davis) decided to take what was a risky assignment. It was a time when women were not supposed to be in active combat situations, if I recall. The desire to prove oneself to others and oneself was not lost on me.

As squad leader, she had to make decisions that led to the death of those attacking her Humvee. And there is one enemy death that she was personally responsible for. A death that when it was depicted on stage, many in the audience cringed—or might have missed. It was such a revealing moment. One that she could have omitted, but she did not. She was very brave to have it on stage; it added to the layers of Heroine. The enemy is out there, what do I do? “How could someone do that?” was what I heard as I left the performance. I chose not to engage them. Also, the depictions of PTS in Heroine both from her rape and the firefight—well, from some other work I have done, I know that is so very real.

And more to your points. My now 36-year-old daughter had a number of young women friends who volunteered for military service. One served in Iraq (flying a military medical helicopter through hostile fire) and one in Afghanistan (Navy Seebee who had to deal with roadside explosives). They would engage me since I had once served and they trusted me as one who would listen and hear them. Their stories made Heroine more than a theatrical performance for me. Why they joined the military. The issues they faced. Why they continued in military service. I will never forget a call received from one of the young women at about 3 a.m. my time. She was somewhere in Afghanistan, scared; suicide seemed to be on her mind. To this day I will never ever forget that call.

John: America has turned a deaf ear to so much trauma associated with military service. A patina of patriotism and an exoskeleton of American exceptionalism seems always to cover that trauma up. I remember a 1997 book by Judith Herman titled Trauma and Recovery that revealed (I think for the first time) that the PTS suffered by soldiers in combat and the PTS suffered by survivors of sexual assault are the same. The fact that The Kennedy Center has brought over Heroine—which puts that trauma center stage—seems to me momentous and makes this an event not to be missed.

I also want to say how much I marveled at the emotional artistry in the way Wells takes us from the horrific through the humorous to an ending that I can only describe as heartrendingly hopeful and healing. Wells means to “speak the underneath,” she says, and she sure does. The fact this is a true story makes its narrative arc all the more moving. And as I left the theater I felt a kind of gratitude to Wells for taking me through it all—and to Davis for allowing her truth to be told.

David: I salute Davis as well for another reason. A smaller number of Americans currently serve in the U.S. Armed Forces than at any time since before WW II. As the size of the military has shrunk and with no active draft, the connections between civilians and military service members have become more distant. For some, military service is for others. In the last data I saw, for those who served in the military after 9/11, about 85 percent say the public does not understand the problems faced by those in the military and their families.

Heroine being produced at The Kennedy Center is truly momentous for it can bring the sacrifices of those who serve to a wider audience to ponder.

Recommended for age 18 and up. Contains triggers, strong language, and graphic content.

Running Time: 70 minutes, with no intermission.

Heroine, presented by the Kennedy Center’s World Stages Program, plays February 12 to 14, 2020, at The Kennedy Center’s Family Theater – 2700 F Street, NW, in Washington, DC. For tickets to upcoming events, call the box office at (202) 467-4600, or toll-free at (800) 444-1324, or purchase them online.

Credits

Written and performed by Mary Jane Wells

Life Story: Danna Davis

Directed by Susan Worsfold

Produced by Sarah Gray

Sound Design by Matthew Padden

Lighting Design by George Tarbuck

Production Management: John Wilkie

For the Heroine website, click here.