By Christopher Lancette

I sit down at Ford’s Theatre a few months ago—back when there was no coronavirus and the world was normal—to watch a play. I have never been much of a theater guy. Not because of a lack of interest but more of a lack of priority: There are so many things I love doing in life each day that the stage hasn’t often made it to the top of my list.

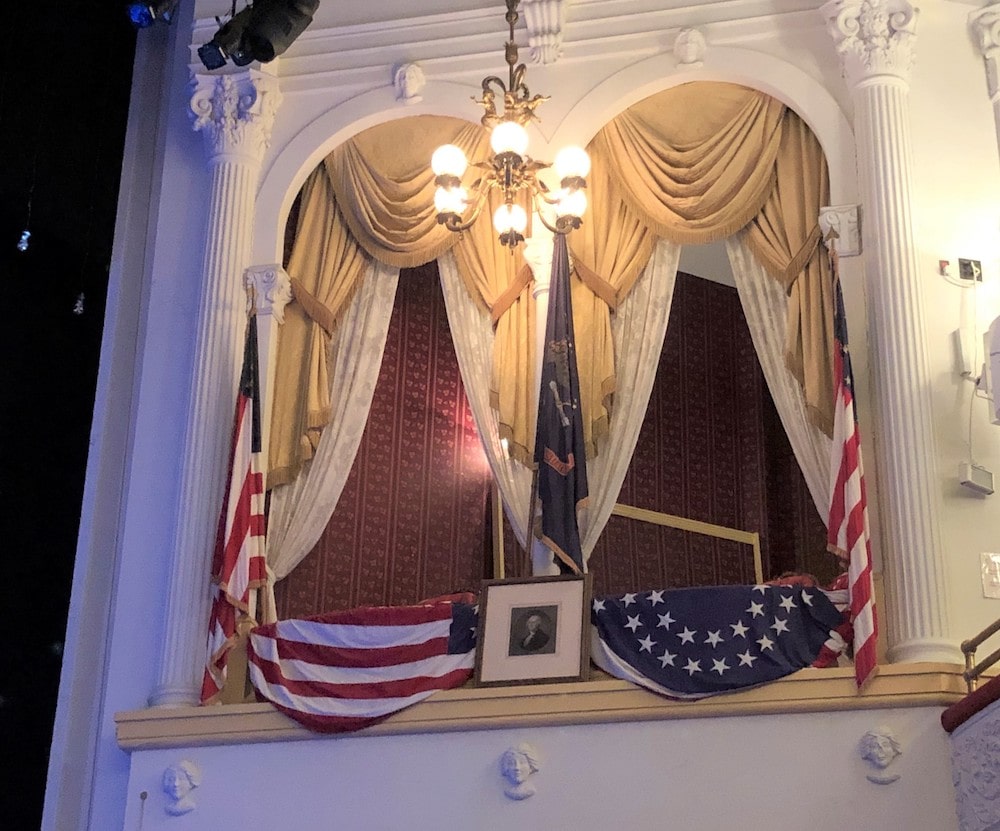

Ford’s, in particular, can be an emotionally difficult place for me to focus. I can’t help but keep one eye on the stage and the other on President Lincoln’s box.

But something about Silent Sky has called me from above on this night. I have to be here.

A play about a real-life female astronomer, Henrietta Leavitt, at the turn of the 20th century overcoming sexism to make a stellar scientific breakthrough? Intriguing.

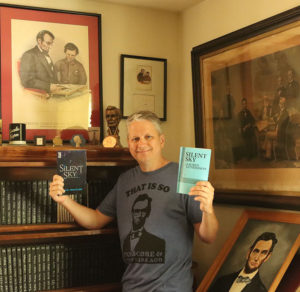

The notice that the playwright will participate in a question-and-answer session makes it more enticing. I don’t know who Lauren Gunderson is—that she’s America’s most-produced playwright or that she hails from my hometown of Atlanta. I just think that listening to such an accomplished creative person might spur me on with my own writing projects.

So I plop myself down in the front row center orchestra at the very edge of the stage, certainly within the periphery of Lincoln’s vision. The longer the play goes, the more powerful his presence becomes. It’s one thing to tour the historic site briefly. It is another experience entirely to take in a play as he did.

To be with him.

Silent Sky simultaneously grabs my attention in the opening scene.

“I have questions,” Henrietta declares to her boss Peter Shaw, immediately upon her arrival at the Harvard College Observatory to begin work in “the women’s room.” That’s where she and two other women in the play (Annie Jump Cannon and Williamina Fleming) contribute to the observatory’s project to photograph and map the entire night sky. They are not allowed to use the institution’s for-men-only Great Refractor telescope themselves. “I have fundamental problems with the state of human knowledge! Who are we, why are we—where are we?!”

Henrietta isn’t going to be content with merely doing her job of studying photographic plates of Cepheid stars and classifying them based on multiple factors including their luminosity. She yearns for more, to look for patterns and meaning—to ask bigger questions.

Oh!, I think to myself. I think I might like this.

There’s humor, too, as when Williamina cuts off one of Peter’s pronouncements in mid-sentence.

“In the history of human thought there was a steady progression of ideas—” Peter begins.

“Unless you’re Catholic,” Williamina quips.

And a love story.

“And I don’t expect you to reciprocate immediately or at all,” Peter stammers, after finally confessing his feelings to Henrietta, “but I feared combusting if I didn’t tell you that you’ve been the brightest object in my day since we met. And we work with the stars.”

The play keeps a breathless pace. I see that it is packed with Henrietta’s romance with stars in the sky and with people on the ground. It is about professional pursuits and personal passions sacrificed. It is about the beauty of living and of dying. It is about the power of asking the question “What’s out there?”

I think I love this!

Peter asks Henrietta to join him on a cruise to Europe. She dreams of how wonderful that would be. The deck of an ocean liner suddenly appears before my eyes on the stage.

What? How did they?— Stunning!

The dream is shattered when she receives a telegram from her sister Margaret back in Wisconsin asking her to come home because their father is sick. Henrietta painfully tells Peter that she can’t go, that she needs to take care of her family and maintain her focus on her work. She implores Peter to go without her and then come back. The two scientists realize that there will be just space and time between them, that they will be “afar, but not apart.”

Beautiful.

Henrietta returns home and finds out that her father’s illness has left him a shell of himself. Margaret shares that the change happened in an instant. Henrietta refers to a new theory by Albert Einstein and tells her sister that nothing changes but simply changes form.

“He says that mass and energy are just different forms of the same thing. They shift back and forth forever. So nothing’s gone. It just shifts.”

My mind races at warp speed trying to digest the power of those words. I think of what I believe happens to people after we die. I have my doubts about the traditional Christian concept of heaven but I’ve always been able to connect to the spirits—the energies—of people from the past—historical figures like Lincoln and my own loved ones. Dogs, too. I feel them in my heart. I talk to them in my head. We are … afar, but not apart.

I don’t have time to finish the reflection as the crescendo of the first act is hurtling through space and time. Margaret is playing the piano for Henrietta, whose mind is churning, always seeking to find some more significant pattern and meaning to the blinking and brightness of her Cepheid stars.

“Oh my God,” Henrietta says, startling her sister.

“What?”

“It’s tonal … The stars are music.”

“My music?”

“The pattern,” Henrietta says. “The numbers — When you put them in the right order — they’re — Oh my God the blinking is music — so simple — Right there! … The pulsing isn’t random. There is a pattern. The brightest stars take the longest to blink.”

Henrietta conveys to Margaret that a pattern is a standard, and that if there’s a standard, you can compare stars all over the sky.

She takes over the piano and pounds the keys to explain what she means. Each note and thought punctuates the Ford’s Theatre air with a sonic boom. I feel each one in my bones. Henrietta says that the notes represent a star’s brightness. The time it takes for one to go from its dimmest stage (taps a low note in the keys) to its brightest (strikes a high note) tells us how bright a star actually is. That length of time ultimately reveals how far away they are and … “exactly where we are.”

Goosebumps shoot across my arms and legs like comets as the curtain promptly closes on Act 1.

I didn’t take much science in college and was probably the only person at my university to ever drop out of music appreciation to avoid failing. Still, I’m not tone-deaf to the discovery: Henrietta has just done something big.

The play growing more poignant with every line, I find a nearly impossible-to-describe joy is pumping through my veins and yet, at the same time, a sadness washing over me.

I look up at Lincoln’s box, as I’ve been doing all night. I think of—no—I feel dear President Lincoln sitting there. He doesn’t know that he is in his last conscious moments on Earth. Whether I have gone back to sit with him, or he has come forward to be with me, or both, is not clear. I am traversing time, caught up in a mind-bending stage-and-stars shifting that’s happening inside me, or the whole theater, or both. Our beloved president is here on the fateful night of April 14, 1865, because the weary leader simply wants to laugh, and My American Cousin is the hit comedy of era. The Civil War has been over for just five days—and Lincoln is only three days removed from a nightmare in which he has been assassinated.

Flash forward to near the end of the second act. Henrietta is living in a home near Harvard. She’s dying from cancer, yet still giving everything she has to her work. Annie and Williamina stop by to check on her. Annie hands Henrietta a women’s suffrage pamphlet and encourages her to join a march in D.C. the following month. “If we can organize the sky, we can organize our minds to choose our own future,” Annie tells her.

Annie promises Henrietta that she’ll send more work for her to do.

“Thank you,” Henrietta replies. “All I have is time and all I haven’t is time.”

I’m not sure I fully understand that, I think, but it’s profound. Like reading some complicated passages from Thoreau. I don’t always comprehend them fully—but I like them.

Peter rushes into the home with big news.

“There’s a new finding,” he says. “And I don’t think I’m overstating — it changes everything. And you had to be the first to know.”

He informs Henrietta that other scientists have used her work to prove that some stars are thousands and thousands of light-years away. Henrietta realizes that this means it’s also possible that our Milky Way Galaxy is just one of many. “Perhaps one of many … billions,” Peter exclaims.

Margaret enters the room and asks about the commotion.

“Henrietta just became the first person to measure the universe,” Peter says, letting the thought waft through the air as he exits.

Margaret asks the next key question: “How do you celebrate measuring the universe?”

The other characters fade away as the last scene begins. Henrietta stands in the spotlight alone and speaks to me. That’s how it feels, at least. Music accompanies her monologue.

Henrietta reports that her friends took her to The Great Refractor telescope, where they break in so that she can at last gaze at the night sky herself—“my heaven,” she calls it. Her cadence quickens, hitting warp speed and blurring the stars outside like the view from a spaceship window as it rockets through the cosmos. I grab hold of my armrests and hang on for the ride.

“Sometime from now I gather myself,” she says. “And sneak outside — and look up. In perfect silence. And I know — that distance is only space and time, and for some of us … light. I am out of time. But light has never let me down. And so. I shift.”

Henrietta points up, and she is suddenly standing on the deck of an ocean liner.

She tells me that Annie gets the right to vote next year, and that a man named Hubble shortly uses her work to prove that our galaxy is in fact one of billions upon billions. Henrietta receives a posthumous inquiry about a potential Nobel Prize.

In another few years, Henrietta continues, Williamina dies (and appears next to her on the ship), then Annie, Peter, and sister Margaret die as time continues (they join the ship).

“Then we harness the atom, then orbit the Earth, then stand on the moon. Then a telescope named Hubble, with wings set for space, shows us how vast and beautiful it all is …”

Fantastical Hubble telescope images of swirling galaxies and kaleidoscopic light are projected everywhere. Then the music stops. Silence takes over as the stars reemerge.

“Because wonder will always get us there … Those of us who insist that there is so much more beyond ourselves. And I do.”

A pulsing light surrounds and becomes Henrietta, who becomes a blinking star.

“And there’s a reason we measure it all in light.”

I sit there—dumbstruck, breathless, and crying. I sob as silently as I can in front of the cast of Silent Sky, and President Lincoln.

I am, for the first time in my life, overwrought by the power of the stage. Transformed.

I fight to regain my composure as I approach playwright Gunderson after the Q & A. I look straight into her blue eyes and confess: “This is the first night I have ever cried in a theater.”

Gunderson leans back in her purple Converse All-Stars with splashes of pink that match the highlights in her light brown hair. She clutches her heart and smiles at me.

My first theater crush.

“Thank you for crying!” she says, returning my gaze and reaching out to give me one of the greatest bear hugs I have ever received.

I make my way up the aisle toward the exit but stop to look back at the stage. I soak it all in, then look up at the president. My intestines tighten as I close my eyes and travel through time once more.

I wish with all my might that Lincoln’s last thoughts are filled with the very same rapture coursing through mine.

Christopher Lancette is freelance writer in Silver Spring, Maryland. Find his work at Salon.com and EyeOnSligoCreek.com, and follow him on Twitter at @chrislancette.

RELATED:

Amy Kotkin’s review, “‘Silent Sky’ at Ford’s Theatre celebrates early female astronomers who reached for the stars”

Ravelle Brickman’s feature, “Behind the lines: Laura C. Harris talks about seeing stars in ‘Silent Sky’ at Ford’s”

Another fantastic Chris Lancett piece- demonstrates his clever view and interesting take.