By Neal Davidson

“Dramatic Betweenness”: A new theatrical experience

Here’s an incredibly simple idea: a play written and performed as a video call. Nothing more. Not a streamed live production, a Zoom reading, or a play produced on a virtual stage. The play is just the call. Characters log on, interact as they would on a normal call, and log off. You just watch. You’re invisible to them. And here’s the surprise: you experience the action and intent of the play from a perspective that has never been possible on stage or screen. I call it dramatic betweenness.

Betweenness draws us inside the struggle of the play, inside the moment, inside the moral dilemma or ethical debate the writer has constructed. And being inside the debate can get inside of us in ways never before possible. No other medium allows for such intimacy or dramatic experience. In live theater — even standing on stage — you can’t see each player’s face, each reaction, simultaneously. Nor can this happen in film or TV, where what you see and when you see it has been predetermined by an editor. Betweenness means experiencing every instant and every nuance of other people’s lives, from within. Our brains are wired for betweenness. We read each other face-to-face. It is the foundation of intimacy. This convergence of consciousness and technology is a new frontier for performing arts. It has the potential to change not only how we see and think about theater but also how we see and think about one another. I believe that as artists, we are obliged to explore its promise.

For ten months in John Dapolito’s Master Class for the Working Actor, we have explored the conventions of acting, adapting, directing, and design that make dramatic betweenness work. We’re a group of dedicated artists, led by a visionary teacher and director, who have used cell phones, laptops, Zoom, PowerPoint, our bedrooms and apartments, and ingenuity to create incredibly intimate and accessible live performance. I would like to share what we learned and empower you to join us in this exploration.

Tape: Discovery

The power of dramatic betweenness became evident during master class work when we began rewriting our scenes as Zoom calls. We didn’t try to pretend we were in the same room. No virtual backgrounds or matching sets, no acting like we could see each other through the sides of Zoom boxes, no passing props through cyberspace. Everyone in class would simply turn off their cameras and microphones while the actors in the scene would stay on screen and behave just like they would on a real call. It worked. We invited some experimental audiences. Not only did they buy it, but they wanted to experience more. To get this work out to the public, I founded a production company, TheSharedScreen.

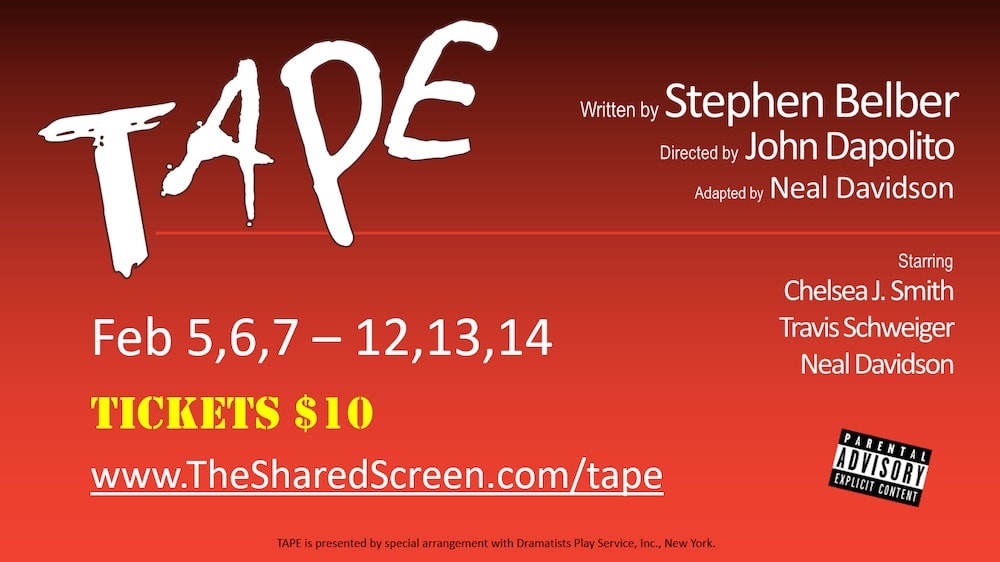

Out of that incubation emerged an adaptation of Tape, by Stephen Belber, the Tony- and Emmy-nominated writer/director. We discovered it was a perfect fit for this medium. It adapted well to the setting of a call, and it raised profound and intimate questions. Stephen Belber graciously supported us in adapting his work. After a successful run in September 2020, Tape has been extended for two more weekends, February 5, 6, 7, 12, 13, and 14, 2021. If you can join us for a live performance, you will see exactly what we mean by dramatic betweenness and how we’ve applied the discoveries we made (there are a lot!).

In our adaptation, Vince, a cocaine-addicted drifter (played by Travis Schweiger), logs in from his room at Motel 6. Next Jon, a self-absorbed aspiring filmmaker (played by yours truly), joins the call from a classy hotel downtown. Later Amy, an empowered and self-possessed prosecutor (played by Chelsea J. Smith), will pop on from her upscale apartment. The screen is set (so to speak), and a Zoom call is established as the medium through which this high school love triangle will be forced to face accusations and denials of rape ten years later. Our production, directed and designed by John Dapolito, pitches viewers face-to-face with these questions in real-time.

Here are some nuts and bolts. The show is produced as a live Zoom Webinar. Audience members (Attendees) are locked in “gallery view” with their cameras and microphones disabled. All you see are the players. Before the show, there is a 30-minute virtual lobby complete with pre-show music and program information. The lobby slides are controlled by our Host, a combined stage manager and board operator, who is screen sharing a PowerPoint. In the background, actors are logged in as Panelists, ready and waiting. As soon as our first actor pops on screen…bam! You’re tapped into one intense call. We hold a talkback immediately after each of our shows. For us, these are essential. In a medium performed and experienced from isolation, they are the only chance for the audience and artists to connect. They catalyze the impact of the experience into actionable and even healing conversations.

Writing and Adapting: “It’s just a Zoom call”

Dramatic betweenness demands that a call be nothing other than a call. Characters log on. They have a video call. They log off. Anything else breaks the spell. It triggers disbelief.

Here’s our rubric for what works great. Take a few real people with storied relationships and strong opinions. Put them in a simple, everyday setting. Then confront them with complex and charged ideas. After working on Tape in class, we knew that it checked all these boxes — real people with messy history, psychologically thrilling twists and turns, provocative ideas, and deep questions that spark meaningful conversations. We know that it works. Our audiences agree.

Justify the call. The first character on-screen needs a reason to be there. Once they are on, they have a few moments alone, waiting. Take this chance to illuminate why they logged on, justify the next character’s entrance, and set the tone. In Tape, Vince starts the call, takes a bump of cocaine, dictates a voicemail into his phone (“Hop on Zoom dickhead!”), and then dances wildly to the punk rock he blasts from his boombox. The audience knows that Vince started the call because he wants to talk to whoever just got that voicemail, and they get the sense this is going to be a wild ride. Jon, having received the message, logs in from his phone. He’s half-dressed in the bathroom brushing his hair, and the audience immediately learns that these guys are getting ready to meet up for dinner. Later on, Vince gets a call on his phone from Amy. He invites her to “hop on Zoom for a second” and tells Jon, “She said she’ll be on as soon as she’s done drying her hair.” Now her entrance is justified. Even better, by hinting at her impending entrance, we use the construct of the call to build suspense — she could pop on any second.

During the call, minimize time and location changes. Stephen Belber wrote Tape as three characters in one room for 90-minutes in real-time. In adapting the play for Zoom, I had only to justify them logging in from three different locations. Scene changes are difficult for actors and tech to execute completely quickly and smoothly. Any pauses in the call momentarily break the betweenness. The snappier and simpler your structure, the better.

Avoid talking heads. Yes, a character’s main action during a call is to talk (it’s the only reason to ever make a call), but be sure your characters have plenty of opportunities for physical activity. Readying for a night out and the bitter accusations and denials of rape that happen in Tape give plenty of motivation for characters to move.

Justify the logoffs. If a character is about to log off, it’s as simple as saying “I’m logging off” or even “I’ll be right back, I swear.” It’s perfectly within the reality of Zoom for a character to log back into a call they were just on.

Use your final moment. The call will end as it began, with one character left alone on screen to end the call they started. Take creative liberty, maybe a final tableau, a little action before ending the call, or just a breath of reflection in the aftermath.

Stay in the technological present. This might go without saying, but Zoom didn’t exist until 2004. Make sure your material is updated or current enough to believably take place over a video call.

Acting: You and your tiny camera

The lens is both your scene partner and your audience. This was the first and most important discovery we made as a class and we practiced it rigorously. Act directly into the camera and you make eye contact with your partner and your audience simultaneously. It’s how betweenness happens. If all actors look at the camera, the audience sees them having a conversation. Yes, in real-life Zoom calls, people look down at the faces on their screens all the time; but your audience has seen side-by-side talking heads looking into the camera on the nightly news, so they get it. “But wait,” you say, “If I’m looking directly into the camera lens then I can’t even see my scene partner!” Correct. Initially, this is gonna feel crazy. You will be acting with a partner you can see only out of your peripheral vision. You may feel you would be having a more honest conversation by looking at the other actor on the screen. Don’t. Looking away is a normal part of conversation, just make it real. If you unintentionally glance down to catch your partner’s image on screen, it’s going to look like you’ve been distracted by some bug on your desk.

Communicating through the lens is your character’s primary action at all times. Early in our exploration, John Dapolito instilled in us that on Zoom all characters’ primary action is to have a conversation, to be understood. It’s the reason they are on the call. In theater or film, a character’s activities and tasks can be more important than the conversation. On Zoom, iron your shirt, but glance up to the camera while you do. Brush your hair, but pause to speak to the lens. Go grab a beer, but throw your line over your shoulder so the microphone picks you up. It’s also a way of cheating to the audience without breaking the reality of a private call. In fact, it will subtly reinforce the constraints of Zoom. The viewer might not even notice the little voice in their head that says, “Oh, yeah! Sometimes I do talk a bit louder on Zoom to make extra sure someone hears me.”

If you’re in a continuous closeup, you are also in a continuous reaction shot. As long as you’re on screen, you’re in your own shot. Never stop listening and reacting to the camera. The audience sees everything, and they learn just as much (or more) from the unspoken reactions as from the lines. Fill each moment with behavior and intention. The audience is always watching, in-between.

Motivate logging on and off and camera movements — these actions are just as much part of the play as getting dressed. You control your own entrances and exits by clicking your camera icon on and off. Think of it like throwing the door open or slamming it shut behind you. Don’t wait until you are on-screen to start acting or drop out of character as you click to log off. It’s painfully obvious. The same goes for camera movements. In life there are plenty of reasons to adjust your camera angles and distance. Consider and explore what motivates people to stand and tilt the camera back or pick up, put down, or even throw their phone. Use the technical elements of video calls as fertile ground for artistic discovery.

In rehearsal, get to know the boundaries of your frame like the back of your hand. It will free you to move. You won’t accidentally take a position that cuts off the top of your head or half your body for a scene, and you’ll be able to keep your gestures in frame without having to cheat down to check your own image on screen. Knowing the bounds of your box will also help you be your own highly effective camera crew (more on this under Directing).

ISOLATION WARNING: Combating the side effects of acting alone in your room

Performing in this medium can be a totally disorienting experience. When the show is over, you don’t even get to leave the stage. You are suddenly alone with all that emotion, yet still on set and in costume. There is no chatting in the green room or on the walk to the subway, no pats on the back to celebrate the opening night. When our team logs back in for our post-show debriefs, we’re still on Zoom! Two minutes ago, Chelsea, Travis, and I were shredding each other’s lives as Amy, Vince, and Jon. Now we’re still in those same boxes on the same screen, wishing we could hug each other from hundreds of miles away.

Then when I shut my laptop for the night, it’s just me. Ten minutes ago, I was a different person and I was in that person’s bathroom in a different city. Now I’m me, brushing my teeth in my bathroom, listening to my favorite song.

As a team, we’ve developed routines that give us time to connect just as people. These rituals are vital in a disembodied world. At the top of every rehearsal and before every show, we check in with each other. John focuses us on the job at hand. We run our tech. We dance it out to our theme song. After a show John checks in with us about how it went and we go over notes. Then he’ll switch gears. An excellent storyteller, he often shares an inspiring anecdote or two to help us return to ourselves, then graciously logs off first to give his actors a moment alone together. We actors virtually hug and let our characters go for the night. These rituals keep us sane and build our ensemble. Every moment we spend interacting as people on Zoom, we get better at being characters in Zoom.

Directing: Working the cameras for “cinematic synergy”

Directors in this medium have a new compositional challenge: the cinematic synergy. How do standard cinematic conventions synergize when they appear live side by side on the same screen? What happens when you can combine a closeup with a long shot? A handheld shot with two still shots? A high-angle shot next to a low-angle shot? Not only did John block, shoot, and direct actors on multiple sets simultaneously, but he also guided us in exploring and discovering how to use these synergies to punctuate key moments, foreground the questions and ideas that drive the play, and create a visually captivating experience for the audience.

Set the screen with believable but revealing sets. John helped us create boxes that subtly illuminate each character’s internal world and cue the audience to know what to expect from the character in that box from the moment they appear on-screen. How about a drifter stirring up trouble from his beer-bottle-and-laundry-strewn motel room (Vince)? Or a district attorney stating her case from her exquisitely neat home office (Amy)? Then consider the juxtaposition of the boxes on-screen. Do they visually correspond or contrast? Does one particularly stand out? These decisions define how characters relate to one another. Intentional boxes make for a great canvas.

Control sequence of entry to put the right character in the driver’s seat. Whoever logs in first will be anchored to the left side of the screen. We have discovered this to be the power position, like the head of the table in the conference room. Possibly because people read left to right, it seems that the audience intuitively glances back to that character to catch the start of the next wave of action. Put the character who is driving the scene in that first box.

Use distance to visually track emotions. Distance from the camera can telegraph several things. It can parallel intimacy: A couple in a fight backs up in side-by-side long shots, making space as things get heated, then get in close as they make up, trying to reach each other. Distance can also show confidence. An actor closes in to drive home an important point or backs off to the edge of the frame when confronted with an ugly truth. A side-by-side midshot feels relaxed and common because it’s the standard distance for Zoom conversation. One actor in close shouting into the camera to make themselves heard by the other actor in a long shot telegraphs desperation.

Use camera angles to suggest status. Ever notice that you sometimes feel “looked down upon” in a Zoom meeting? Staring at a screen full of people with their laptops placed low in their laps so they are all “looking down their nose” at you? As a director, you can use this intuitive sense of scale to your advantage. If a character is “talking down” to someone, or “taking the moral high ground,” have them tilt the camera back and stand up. If a character is “feeling small,” shoot them from above.

Use cinematic transitions to punctuate beats. Every major visual shift — be it backing up to a long shot, tilting the camera, or switching from phone to laptop — lands on the audience like cuts between scenes. We had several audience members ask about how we were cutting between multiple cameras that were shooting simultaneously…we weren’t. We used one camera each, like a normal call. But the way that we moved those cameras, embracing different combinations of shots and angles, gave the audience a sense of depth and space that is surprising on Zoom.

The ace up your sleeve: the Zoom pause. It’s visceral. Remember that uncomfortable cringe you felt at even a few seconds of delay the last time you saw a Zoom interview on the news? How about that awkward silence in your last meeting? We get on Zoom to do one thing: talk. So when that one thing stops, it jolts us. If your show has been plowing along as it should, an intentional pause will suck the air out of the Zoom. Pauses work. Use them sparingly to great effect.

One last trick: the phone switch. You can’t shoot the same set from two devices at once; that character would suddenly appear in two boxes on screen. However, you can justify in the script that a character changes devices mid-call. As Jon during Tape, I switch from my phone to my laptop upon leaving the bathroom. It takes some practice to smooth the process of quickly shutting off the camera and microphone on one device while turning them on on another; but when an actor gets the button pressing down, the audience doesn’t bat an eyelash.

Lights, Camera, Sound, Internet!: Keeping it Zoom

Keep all your tech true to a Zoom call. The audience will be jarred by anything that doesn’t play by the rules of a normal call. Nobody will believe that a perfectly lit and miked soundstage, seen through 4K video, is a Zoom feed from a Motel 6. This isn’t an excuse for poor resolution and sound or lagging internet. Trust me, we’ve done all (and I mean all) we can to ensure smooth tech, but anything more than that ruins the magic.

Use a good webcam. Newer laptops have built-in cameras that can suffice. If not, you can invest in an HD USB webcam. I recommend securing it to your laptop with something more than just gravity (read: velcro). You don’t want your camera flying away when you adjust the angle of the shot. Cell phones these days tend to have excellent front-facing cameras. I’m glad the selfie has paved the way for ethically charged theater.

Use a good mic. Most webcams come with built-in microphones that sound great. If the microphone on your laptop is distractingly bad, get a good USB mic that you can hide just outside of the frame. I don’t recommend a lavalier because…who wears one of those for a normal Zoom call? The same goes for headphones. As actors on Tape, we listen to each other through the same audio feed the audience is getting. You could make headphones an intentional and justified character choice — just make sure they aren’t going to fly off during your Oscar-winning moment.

Get the highest-speed Internet you can get, from reliable providers, especially if you are hosting the webinar. Test your internet speed repeatedly in the weeks leading up to the show during the time of day you will be running the show. It helps to make this a pre-rehearsal habit. Don’t trust Wi-Fi. Use an ethernet cable to plug into your network. Make sure your actors have cell phones charged, connected to data (not Wi-Fi), and already logged in to the webinar as panelists. This will cover you in case Wi-Fi or power goes out on their end. During one of our shows, my laptop started to lag and then completely crashed. While it was failing I ad-libbed something about seeing a lag and switched to my phone for the rest of the show, propping it up against my dead laptop screen. No one in the audience noticed.

I want to emphasize that this medium is financially and technologically accessible. We are a group of scrappy actors with a dream, spread in isolation across the country, and we made Tape happen using stuff we already had around our homes and apartments. A Zoom Webinar license is far cheaper than renting a theater — not to mention it scales instantly from 10 to 10,000 people, and you don’t have to have parking. With some cell phones, laptops, lamps, and a lot of elbow grease, you have an incredibly intimate dramatic forum.

Creating the Audience Experience: A night-in that sparks a conversation

Live theater, and even going to the movies, involves a sort of ritual: getting dressed, the commute, tickets, popcorn or a program, taking your seat in anticipation, that magical moment of silence just before the performance begins, the breath as you become part of a collective, ready to be led on the same journey. This new medium, shared in isolation, needs a new sort of ritual. I’d invite you to make the popcorn and get comfy. From our end, we needed a new way to help the audience enter into the world of the play, prime them for a shared remote experience, and even bring them together to reflect on it. Good news: you don’t have to write any code or talk to a programmer. If you have Zoom and PowerPoint and know how to press the buttons in the right sequence (granted it is a lot of clicking), you too can create a seamless and engaging audience experience.

If you can, do it live. If your audience knows they are in the story while it’s happening, it’s riveting. We are all engaged in a special moment in time. It wasn’t recorded last week, and no one else will ever see it like this again. There’s no rewind. Not to mention, the actors are working live hundreds of miles away from each other. Magic! It also adds a level of risk and, dare I say, respect for the performers. The audience realizes that the actors are swinging without a net, vulnerable. Missed cues, a fumbled word, mistakes are all real. Finally, sharing in real-time gives a sense of communal experience and connection that we later harness in our talkbacks.

Our “virtual lobby” is a PowerPoint presentation we screen share along with pre-show music for 30 minutes. It includes bios, acknowledgments, history of the show, donation information, content warning, and closed caption and talkback directions. This gives the audience a moment to breathe, double-check their speakers, and it removes their ever present fear of suddenly appearing on everyone’s screens with their wine and ice cream.

Our director, John, appears on-screen and gives the Zoom equivalent of a curtain speech. He offers acknowledgments, thank-you’s, a brief background of the material, and a content warning and repeats technical information, invites the audience to join us for the talkback, and gives a warm “Sit back and relax.”

We transition into the show with a simple cinematic introduction. In the movies, you get the credit sequence. Onstage, the lights dim with accompanying sound effects. On Zoom, we just share another PowerPoint. We sync fifteen seconds of images and sound to set the tone and give the audience a sense of the characters’ locales. Then boom! Travis pops on.

After the show ends we share another sequence of slides, with credits, the team’s headshots, thank you’s, and more music. This functions the way bows would in a theater; it gives everyone a moment to return to themselves.

We’ve learned that talkbacks are an essential part of this medium. Talkbacks after Tape have sparked profound, impactful, and even healing conversations about the subject matter of rape, truth, ownership, and empowerment. It seems that when the audience has been in the conversation for 90 minutes, they want, and deserve, a chance to participate. Let the audience join the forum. Originally we used talkbacks to get the audience’s feedback on their experience with this new medium. We quickly realized these talkbacks were something so much more. The conversations turned from “It’s amazing how you operate your own cameras” to “I’m 84 and just want to share with everyone that this play taught me something new about life and human nature.” Talkbacks are a way of exploring the impact of the play and translating it into our lives.

Join In: “I’m sending you the invite”

So there you have it. There is a simple, readily available technology that by its nature connects us in unexpected ways. It creates a new medium of artistic expression. It opens a new theatrical window — dramatic betweenness — through which we can experience one another’s lives more intimately than ever before. In an isolated and polarized world, it can tether us. Join in, it’s just a click away.

About TheSharedScreen

About Neal Davidson

To foster the creation and production of new works in isolation, Neal founded TheSharedScreen. He adapted, produced, and is starring in Tape. He offers private coaching to actors, speakers, and educators on how to act, audition, and present on Zoom. Neal is an actor, writer, producer, and coach who believes that art must raise ethical questions. In this pursuit, he passionately writes and plays characters faced with high-stakes moral decisions and sacrifice. After graduating summa cum laude from Northwestern University’s theater program, Neal moved to New York City where he signed with Avalon Artists Group and founded Right Take Studios to produce short films, YouTube content, web series, and reel footage and coach auditions. When New York locked down in March, he was on his way back to the city from Georgia, where he had just finished playing Spike in Savannah Rep’s production of Vanya & Sonia & Masha & Spike. He paused just outside of Washington, DC, his current base of operations.

Special appreciation to…

John Dapolito and the extraordinary artists in his Master Class for the Working Actor for their support of this project and their creativity in exploring the potentials of this medium. None of this would be possible without: Anne Windsland, Brian Kelly, Conor McGee, David Williams, Derek Michalak, Elise Gainer, Hunter Emery, Jennifer Kalajian, John Crandall, Justin Rowe, Kristin Noriega, Lara Silva, Laura Petersen, Maureen VanTrease, Milagros Simon, Monica Afesi, Nicole Vande Zande, Patrick Hamilton, Ryan Clardy, Sarah Doudna, and Jimmy Wirt.

A note on rights, licensing, and contracting

If you are adapting a published play, respect the writer, and apply for adaptation rights through the licensing organization. Writers will need to sign off on all changes to a published script. Contracting performers and personnel in this medium is a developing landscape. Be sure to research the latest policies and procedures.

What an insightful, behind-the-scenes look at a truly amazing performance. Thanks Neal!