Hermione Lee’s biography of Tom Stoppard is a comprehensive look at the life and work of one of the English language’s most accomplished playwrights. Lee, a prolific biographer of 20th-century writers, including Virginia Woolf, follows Stoppard from his birth in Bata, Czechoslovakia, in 1937 to the early closing of his most recent play, Leopoldstadt, in March 2020 due to the coronavirus. Stoppard has continually said how “lucky” he has been in his life, and this book seems to bear it out. Born Tomáš Straussler, he fled with his family first to Singapore then to India when the Germans invaded Czechoslovakia. His father died trying to join them, but his mother would later marry Ken Stoppard and move her two sons to England. After he worked as a journalist in Bristol and London, including reviewing theater and film, his play Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead launched him into fame. The premiere at the National Theatre, after a middling run in the Edinburgh Fringe Festival, was almost an accident, as the theater’s upcoming season was up in the air. Thanks to one great review, it became enormously popular, with audiences finding it “entrancingly cool, modern and desirable.”

Many of his plays, like After Magritte, begin with a scene that seems to make no sense before revealing the logical explanation behind it. They surprise the audience, making them work to understand what is going on at first. Indeed, throughout this book, Stoppard explains, in interviews and rehearsals, his reluctance of “over-explaining” in his plays, wanting the audience to do some of the work while watching it.

While his intellectual side is certainly evident, Lee discusses the incredible human feeling in Stoppard’s work. For example, while the idea behind The Real Thing is certainly complex (the first scene being from the play of the writer introduced in the next scene), its honest look at “love and marriage and friendship” feels powerful. Lee writes of the “personal effect” the play had on many people, citing a fan who wrote that couples might use the play’s lines to say “There-that-that’s what I mean. That’s what I was trying to say.” Stoppard admits that during this time, he was “shedding his protective skin,” expressing more emotion and being more vulnerable.

Although his plays are not strictly autobiographical, Lee shows how elements of his life found themselves into his work. Rock ‘n’ Roll was partly inspired by his wondering what his life might have been like if he had returned to Czechoslovakia after World War II and had to live under a Communist regime. His friendship with dissident writer and president Vaclav Havel, as well as Havel’s support of the Czech rock group Plastic People of the Universe “only interested in music” but imprisoned for it, was also a major influence. Rosencrantz partly emerged from his memory of Peter O’Toole in Hamlet.

Lee also explores Stoppard’s screenwriting career. He has worked on many different films, perhaps the most surprising being for Cats, done because he loved the T.S. Eliot poems the musical is based on and enjoyed the “puzzle problem” of finding a plot into which he could put the songs; sadly, his version was not made. While he might be best known for Shakespeare in Love, it was not his idea or his title. Some of the films he has worked on uncredited include Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (dialogue between Indy and his father) and Hook.

Stoppard feels an extraordinary love for his adopted country, defending its institutions. He was a supporter of Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, having lunch with her and Reagan. His friend Antonia Fraser comments that he was one of their most “right-wing” friends. Sometimes his conservative views caused disagreements between him and his other artist friends, as when he allowed productions of his plays in apartheid South Africa. Lee carefully explores his thinking, showing that he was interested in the freedoms offered in England, especially that of the press, that were not available in many other places. In later years, he would take a more liberal view, perhaps, as Lee suggests, under the influence of his partner Sinéad Cusack. Whereas in Night and Day, he argued that some hack journalism might be the price to pay for the press’s freedoms, more recently he has raised concern over the change in British media culture that led to the notorious eavesdropping scandals.

The book’s look at Stoppard’s personal life shows him to be honorable and loyal, even during difficult situations, such as his first wife Jose’s mental health struggles. While he grew up in a family that was not open with their feelings (his brother told him about their mother’s pregnancy with their half-sister), he formed lasting friendships and relationships. Even his exes have nothing but love for him. It is possible that this is because Stoppard is still alive and he chose Lee as his biographer, but he seems to inspire love. With an easy style, Tom Stoppard tells the compelling story of a talented, beloved writer.

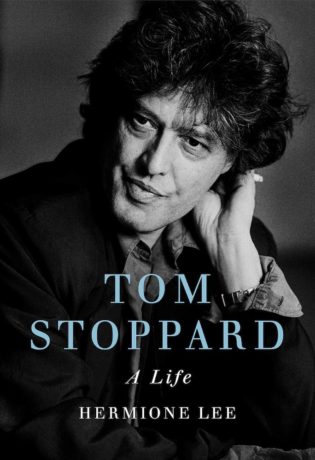

Tom Stoppard: A Life by Hermione Lee

Knopf. 896 pages, $35.49. Publication date: February 23, 2021.

In 2018 Hermione Lee interviewed Stoppard at the 92nd St Y in New York. They discussed, among other things, his play The Hard Problem, which was set to open at Lincoln Center.