Post-Play Palaver is an occasional series of conversations between DC Theater Arts writers who saw the same performance, got really into talking about it, and decided to continue their exchange in writing. That’s what happened when Senior Writers and Columnists Sophia Howes (Dangereuse) and John Stoltenberg (Magic Time!) attended the sound-and-light experience Blindness now playing for limited audiences seated socially distanced and masked on the stage of Shakespeare Theatre Company’s Sidney Harman Hall.

John: I remember my unease when Shakespeare first announced there would be a run of Blindness last December. At the time—as COVID was on a rampage—I could not imagine sitting for an hour and a half indoors with several dozen strangers anywhere, much less at a theater. Since the pandemic began in March 2020, I had not been able to imagine focusing on a live performance of any sort without being distracted by anxiety about getting infected. And I remember my relief when late in November, DC Mayor Muriel Bowser announced restrictions on entertainment venues that meant Shakespeare had to call off its run of Blindness.

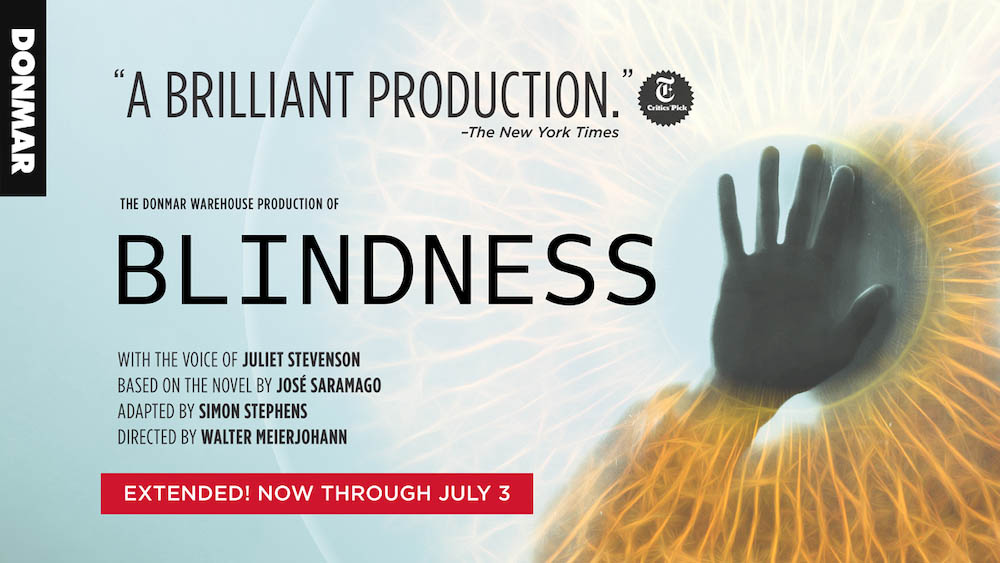

That was then. Blindness has now been running for real at Shakespeare since May 1, 2021. (See our colleague Susan Galbraith’s rave review. Sold-out houses have prompted STC to extend the show through July 3.) And I still can’t get over the sense of giddiness I felt when I knew I would be experiencing it myself, in person. This would be my first time inside a theater in nearly 15 months. I was vaxxed and psyched and eager to take it in.

Blindness is adapted from a novel by Portuguese Nobel laureate José Saramago about a mysterious epidemic of blindness that besets the population of an unnamed place. People inexplicably go blind. They suddenly see everything as white. We are told the story aurally through headphones as we sit in twos under multicolored fluorescent lights that episodically go out and leave us in pitch darkness. Much has been made of the relevance of Blindness to our present pandemic, but what struck me right away was how little that current context mattered to me as I was following the tale. I was sitting there feeling a personal immunity that left me at liberty to experience the production not as a trenchant pandemic metaphor and ingenious workaround (which it is) but simply as innovative immersive storytelling stagecraft. So it was that I found myself more entranced by the techniques and technology than moved by the narrative as resonant allegory.

Would I have felt more personally invested in the story if I had felt more personally fearful of today’s plague? Perhaps. But had I not felt so free of personal risk, I would never have dared venture inside. Call it a Contagion-22.

Sophia: The moment that really knocked me out was when the lights rose on the empty theater auditorium. This symbolized for me all the lives we have lost in the pandemic. In a way, it’s hard to grasp. Each person has their own story. And the numbers are so overwhelming.

For me Blindness was a beautiful piece of poetry. The lights coming on and going off. The sounds. The sense that no matter what happened we would not escape. And yet there was also beauty. The music. The careful arrangement of the words. An extended metaphor, so relevant to our times that it can be applied to many different situations.

I once became blind in one eye due to a botched operation. The doctor, an arrogant sort, laughed and referred to it as debris that would clear up. It didn’t. It was like a curtain coming down. They had to do another whole operation, and it could happen again at any time. I try not to think about it. It was a very limited experience, a snapshot of what being blind must be like. I have no idea. Which is why the parts when we literally could not see were so powerful.

On another level the piece is about human cruelty. The blind people seem to be helpless and are treated terribly. The narrator attempts to help but also joins in the cruelty to some extent. She seems emotionally detached from her husband. Her response to the carnage is largely to attempt some form of practical assistance. But she doesn’t ask the blind people what they need. Nor does she connect personally to her husband’s pain. Perhaps the trauma has numbed her.

We don’t know what the blind people are thinking. That was a question I had. What are they thinking?

John: During passages when all the lights are out (including the exit sign) and we sit motionless and voiceless in a claustrophobia of total darkness, we are sightless witnesses with only our hearing to know what’s going on. And at such times there is a sense in which we become the silent blind population in the story. Or so it felt.

Perhaps to make the point, every so often the lights blaze on in an instant with a brightness so glaring it forces our eyes to adjust. Then light lingers as an afterimage on our retinas like a glimpse of the whiteness the blind in the story are said to see.

The light and sound tech serve the aural narrative in mind-altering ways. What is happening in the story is indivisible from what is happening to us.

We wear headphones with uncanny 360-degree audio, which conveys a spatial dimensionality unlike anything I’ve ever experienced. The narrator’s voice we hear throughout is the wife of a now-blind ophthalmologist, and she alone among the internees in quarantine can still see. When she spoke intimately just behind my left shoulder as if only to me, it was so convincing I felt that if I turned my head I might face her and feel her breath. In another moment I could hear her excruciating cry coming from some echo-y chamber yards away. At another point when she discovers a storeroom of food, her sheer vocal joy and pleasure was so infectious I could not help smiling unseen. At yet another juncture as pouring rain fell everywhere in torrents, I heard her desperately trying to wash, to clean “the filth of the soul…the filth of the body….it’s all the same.” The story was incessantly surrounding me in my hearing and moving around in my mind, and I felt peculiarly present and drenched in it.

Something had been altered in my sense of hearing, I realized later as I was taking a walk in the woods. I was newly attuned to the immaterial soundwaves that signal spatial dimensionality in real life. How far distant is that specific sound? What precisely is my geolocation in relation to that other sound? “Don’t lose yourself,” the nameless narrator says near the end, “don’t let yourself be lost.” To my astonishment I found myself newly grounded by sound. I felt my ears had learned a new way of knowing where I am.

Sophia: I love this quotation from the novelist Saramago:

I don’t think we did go blind, I think we are blind, Blind but seeing, Blind people who can see, but do not see.

I wonder what it is I do not see about myself or others. I wonder how my own prejudices or upbringing might blind me to things that are evident to other people. I wonder how others might be blinded to certain truths by their own background or set of beliefs.

I have been reading about cults recently, and one of the things I found amazing was that in apocalyptic cults, once the day of the supposed apocalypse occurred and nothing happened, many people would not leave the cult. They would just revise their expectations. This, to me, is a form of blindness. If you have sacrificed enough for something, you are under tremendous pressure to believe in it.

Running time: 75 minutes

Blindness runs through July 3, 2021, with viewing times at 7 p.m. Tuesday to Friday, and at 11 a.m., 3 p.m., and 7 p.m. on Saturdays and Sundays; there are also showings on Wednesdays at noon. Tickets are $49, except weekend and Wednesday matinees, which are $44; all tickets are general admission. Tickets for Blindness are available for purchase now online. All artists, dates, and titles are subject to change.

ENHANCED SAFETY PROCEDURES

Patrons will be seated onstage at Sidney Harman Hall in a socially distanced manner and will never be seated next to someone outside their own party. A limited number of single tickets are available for purchase by calling the Box Office, (202) 547-1122. All patrons and staff will wear masks at all times while in the building, and must stay home if they are feeling ill or experiencing any symptoms of illness. To stay within the guidelines of D.C.’s ReOpenDC plan, the seating capacity is limited to 40 guests and there will never be more than 50 people in the building. Complete information about STC’s Safety Guidelines is available here.

SEE ALSO:

‘Blindness’ in darkness at Shakespeare is a brilliant beacon of theater review by Susan Galbraith

In ‘Blindness’ at STC, the audience is live, with not an actor in sight

Previous Post-Play Palavers by John Stoltenberg and Sophia Howes